Velu and I watched the lights of the power plant flick on about an hour before sunset. With our backs rested to the sides of his boat, we saw red lights mingle with yellow ones, adding touches of color to the white steam that shot out the ends of the plant’s chimneys. Eventually, as the evening sky darkened around us, the power plant appeared to have undergone a remarkable transformation—as if cloaked in a series of shiny ornaments—flaunting the sheer expanse of its presence. Everything that supported the perennial operations of the power plant joined in on the luminous display: the lights on the bridge and on the coal conveyer belt, the streetlamps on the roads, and the headlamps of the large trucks that carried coal into the plant’s premises and exited with copious loads of toxic bottom ash.

Perturbed by this barrage of industrial lights and sounds, Velu burst out in frustration. He lamented the fact that Ennore, a coastal peninsular neighborhood in the northern outskirts of Chennai (India), had become the site of the “company”: a term he used not only to refer to the chain of state-owned coal-fired thermal power plants that towered over us on either side of the river, but also a host of private industries that sprouted across the region. For the fishers who had historically called Ennore their home, a community to which he too belonged, the presence of the company was more than disruptive. To make this clear to me, Velu pointed to the floodlit concrete piers of the bridge we floated beneath and insisted that its construction, while facilitating a road link between the power plants and a few industrial townships west of Ennore, had unleashed a surge of sedimentary deposits that had rapidly blocked sections of the river. Having narrowed the river’s course, the construction of the bridge had also hampered the tidal flows that were essential for the cyclical movement of prawns in and out of the estuary. Besides meaning that he now returned home with a reduced catch, Velu explained, the bridge had made it mandatory that he set up extra sets of nets at any given time, intensifying the bodily load that fell upon him every time he fished. “But who cares about the fisher’s plight?” he exclaimed as truck after truck rode past us into oblivion. “Now, if you look in Ennore,” Velu concluded, his hands twisted in defeat, “the company is everywhere.”

Velu believed the company held considerable contempt towards Ennore’s fishers. He recalled how even after frequent demonstrations, complaints and protests, the state government continued to favor the presence of heavy industry over the fishers’ livelihoods and interests. The rapid industrialization of Ennore and the construction of fossil fuel infrastructures surged with the state government’s shift to neoliberal modes of governance in the early 1990s, thereby respatializing coastal landscapes like Ennore as prime sites to house a conglomeration of fossil fuel industries (Kumar 2022). For fishers like Velu, this meant not only being relocated to make room for one of the power plants, but also witnessing the introduction of cement manufacturing units, fertilizer industries, and commercial mega ports with coal handling capacities. While many could readily point to the physical location of these industries in Ennore, it was their presence in the water that seemed to unsettle them the most. Striding through the river, setting up extra sets of nets in a desperate bid to keep their livelihood afloat, many like Velu equated the added bodily workload that fell upon them when they fished as evidence of the company’s unruly expansions. The extra nets, in other words, were proof that the company was indeed everywhere; silting their river, eating into their livelihood, and detrimentally, even devouring their personhood. Who was he if not a fisherman? Velu had asked me that same day. Who else could he possibly become in his own home?

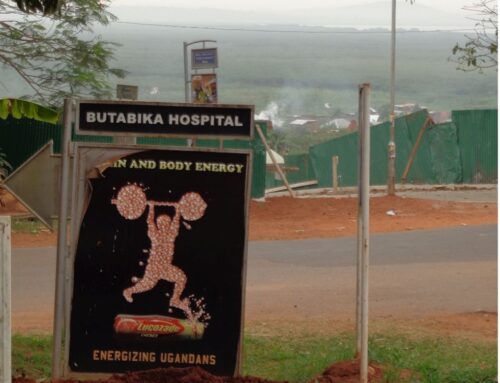

Velu motoring his boat towards his fishing spot in the Ennore river after having crossed the chain of transmission towers and coal conveyer belt that intersected the banks behind him. Photo by the author.

And yet, despite the anxieties that the company’s presence seemed to cause Velu, he dived into Ennore’s waters every chance he had to go fishing. At those moments, Velu engaged with what the authors in this collection have theorized as “living in a mode of despite.” Traversing a riverbed layered in coal ash, immersing his body in a river which he knew drained out all of the power plants’ thermal discharge, noticing the itchy patches of skin on his hands and feet because of the “chemicals” in the water, Velu simultaneously found some form of relief when he engaged in the labor of fishing. As much as it was parts of him that withered away every time he set up those extra sets of nets, losing ground to the company’s contemptuous actions, fishing in Ennore was also some of the most powerful moments wherein Velu reinforced his desire to live and labor in his home. It bolstered his identity as a fisherman and offered him, quite contradictorily, the capacity to assuage the very anxieties that emerged from him being in the river.

Velu’s living in a mode of despite, I believe, is revealing of how certain communities engage with the degrading and polluting infrastructures that are falling apart around us—the telltale signs of what Kim Fortun (2012) terms as the period of “late industrialism.” It also exposes “despite” as both a noun—as in the contemptuous treatment that the fishers believed the state government extended towards their community—and as a preposition—as when Velu dives back into the water to fish in spite of the fears and anxieties that it caused him. It is within this tussle between noun and preposition that the conceptual potentialities of living in a mode of despite unfurl. Taking on the hurt, powerlessness, and incapacity that many feel when engaging with systems of power, the mode of despite is always an affective force that is felt. For fishermen like Velu, the company’s contemptuous actions towards the fishers initially found expression in the sights, sounds, and bodily sensations he felt while being in a river that was facing the brunt of Ennore’s industrialization. Thereafter, through acts of what Nicholas Shapiro terms “bodily reasoning,” where one “tempers not just what one knows but what one becomes with or is estranged from,” (2015, 370). Velu elevated what were feelings of despite into knowing what despite felt like.

Simultaneously, in knowing what despite felt like, Velu found ways to temporarily work away the anxiety it caused him. In other words, he revealed how people work with, “resist,” and/or “refuse” systems of contemptuous power, exposing acts of being and living in the world that emerge from an engagement with what the authors in the introduction have called the “mood of the despite.” In diving back into Ennore’s river, and persisting with the labor of fishing—by acting in a mode of despite—Velu found an antidote to the parallel anxieties that being in the water provoked. It was the only way, in the words of one of Velu’s peers in Ennore, that the fishermen could feel “free” in a landscape that had been recklessly turned over by the company.

What might this freedom mean? How might it be achieved by living in a mode of despite? Anna Tsing stumbles upon a similar question in her work with Matsutake mushroom pickers in the forests of Oregon. Intrigued by pickers suggestion that there was a freedom to being Matsutake pickers, Tsing suggests that this freedom not be thought of in rational economic terms. Instead, she identifies this freedom as “both a way to move on and a way to remember” (2015, 79). For the pickers, this meant that it allowed them to engage with their personal pasts, with the extremes of the law, with the vagaries of a contested landscape, and with tricky buyers and sellers through their search for mushrooms. Freedom, in other words, emerges from a negotiation, one side of an experience that is equally doused in troubling and distressing outcomes—like that of being arrested for trespassing, losing money, or worse still, losing one’s own life—while simultaneously engaging with oneself. I believe it is a similar form of freedom that the fishermen in Ennore felt when they fished in those waters. Along with the anxiety and dread they felt as they fished, emerging from the very same experience, was a sense of freedom. In other words, living in the mode of despite and feeling the mood of despite were forces that could only be known together. Ennore’s fishermen engaged with it every day.

References

Fortun, Kim. 2012. “Ethnography in Late Industrialism.” Cultural Anthropology 27 (3): 446–64.

Kumar, Mukul. 2022. ‘Fossil Neoliberalism and Its Limits: Governing Coal in South India’. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5 (4): 1853–71.

Shapiro, Nicholas. 2015. “Attuning to the Chemosphere: Domestic Formaldehyde, Bodily Reasoning, and the Chemical Sublime.” Cultural Anthropology 30 (3): 368–93.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rishabh Raghavan is a research fellow at the Max Plank Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle (Germany). His research interests include toxicity, environmental pollution, infrastructures and labor in India. He is currently working on his first book manuscript as well as developing a second project about climate change and industrial disaster in India’s southeastern coastline.

Cite as: Raghavan, Rishabh. 2024. “Despite the “Company”. In “Living in a Mode of Despite”, edited by Rishabh Raghavan, Mascha Schulz, and Julia Vorhölter, American Ethnologist website, 3 October 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/living-in-a-mode-of-despite/despite-the-companyby-rishabh-raghavan/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).