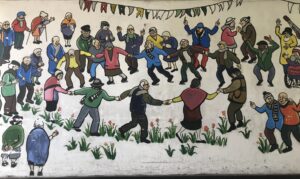

Mural in a shelter for the elderly urban-poor in Lima, Peru, depicting older adults dancing. Photo by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori.

Anthropological studies have underscored aging as a multidimensional phenomenon rather than a singular, universal experience (Kauffman 1986; Lock 1993). Indeed, aging cannot be simply understood as a biological process; rather, its norms and values are a product of culture and of the configuration of socio-political and economic factors that underlie specific social settings (Clark 1967a; Barrientos 2003). While past scholarship on the topic addressed how, in Western societies, becoming an older adult rested strictly on a temporal definition (Fortes 1984), current cross-cultural studies offer evidence of diverse styles and forms of growing old in different environments (Buch 2018; Danely 2022; Allison 2013; Robbins 2020; Lamb 2000; Cohen 1994). Thus, it is clear that aging is far from a “given,” as is what it means to be an older adult.

During the 1980s and 1990s, contributions made to the anthropology of aging tended to be framed within the logics of social indifference and bodily decay (Cohen 1994). Many scholars claimed that avoidance of aging–and the series of negative stereotypes associated with it–came from a shared assumption that late maturity was an abject state characterized by social neglect (Fry 1980; Clark 1967b). While the experience of neglect is indeed a reality for many older people around the world, today anthropologists and other social scientists are also engaged in developing more comprehensive understandings of how late adulthood is interwoven and inflected with topics of global relevance such as migration, digital literacy, queer and trans experience, or other-than-human relations.

This collection, then, reflects broadly upon the difficulties–but also the alternative presents and futures–of growing old. The collection considers the multidimensional forms of aging in these times marked by political unrest, war, COVID-19, environmental depredation, climate crisis, social and family abandonment, economic precarity, and the widespread breakdown of material and social infrastructures of care. Across the globe, the recent COVID-19 crisis showed us how an elderly other, who was seen to occupy the place of the “unimportant,” was left to die both physically and socially under a neoliberal global order that deemed them worthless or expendable. In the midst of that global health emergency, older adults’ very right to exist was contested as they were relegated to the interstices of oblivion and random visibility. Many people growing old under precarious circumstances were deprived of their voices and of the possibility of making demands. Their struggles for survival were clear evidence that they were considered in terms of what Giorgio Agamben has referred to as “bare life” (1998), divested of social and political recognition.

COVID-19 showed us that the inequities of neoliberal globalism produce a differential distribution of social risk that renders vulnerable those who are aging without family support and financial security. This is a reality, especially in countries with poor or disrupted medical infrastructures. As in the Global North, people in the Global South are living longer than they ever have, but under more precarious conditions. Weak public policies, deficient distribution of national budgets, institutional corruption, and broken state institutions threaten the provision of adequate care to older adults. As a result, many people around the globe are aging amidst conditions of loneliness, poverty, and chronic illness.

There is no doubt now that the world’s population is aging. Virtually every country in the world is experiencing growth in the number and proportion of older persons among their population. For example, in Peru, people are living longer and, today, older adults comprise 12.3% of the total population (INEI 2023). In 2007, only 9.1% represented older adults in the country (CEPLAN 2023). Meanwhile, in Europe, together with Portugal, Italy has the highest percentage of residents older than 65 at 24%. That is roughly one in four. This increase reflects a European-wide trend (Euronews 2024). Things are not too different in Asia, specifically in Japan, the country with the highest proportion of elderly citizens (Danely 2014) in the world. By 2050, an estimated one-third of the population in Japan is expected to be 65 and older (International Longevity Center Japan 2017). Population aging is poised to become one of the most significant social transformations of the 21st century, with implications for nearly all sectors of society, including labor and financial markets, the demand for goods and services, housing, transportation, and social protection, as well as family structures and intergenerational ties (United Nations n/d). According to the World Population Prospects 2022, the population above the age of 65 years is growing more rapidly than the population below that age. The proportion of people aged 65 years and above is increasing at a faster rate than those below that age. This means that the percentage of the global population aged 65 and above is expected to rise from 10% in 2022 to 16% in 2050. It is projected that by 2050, the number of individuals aged 65 years or above across the world will be twice the number of children under the age of five and almost equivalent to the number of children under 12 years (United Nations n/d).

Within this context, the fifteen essays in this collection touch upon what it means to grow old in different places of the world and in varying social, political, and economic circumstances. Often, these places and circumstances are marked by the uncertainty of job security (Ahlin and Coe, this collection) and of family belonging (Pauli, this collection); the promise of independence (Lamb, this collection); the overwhelming weight of being a migrant and a refugee (Amrith and Sakti, this collection); the emergent–and often disturbing–prescence of new technologies (Lynch and Diodati, this collection); senses of anxiety and insecurity during times of serious illness and end-of-life care (Hughes-Rinker, this collection); and the manifestation of interembodied uncertainty (Sousa, this collection).

Nevertheless, there is also room for possibility. Some of these essays reflect upon how unsettling worlds can be remade (Douglas, this collection), how gender diversity be accommodated (Pang, this collection), how aging futures can be looked in a new and proper way (Pieta, this collection), how care for people with dementia can be framed differently in religious terms (Daher-Nashib, this collection), and how expanding public intergenerational engagements in communities across Mexico can remake reality (Sokolovsky, this collection).

We present to you the latest AES collection: Aging Globally: Challenges and Possibilities of Growing Old in an Unsettling Era. We hope that these essays inspire critical thought and reflection for our readers. Overall, this group of essays address the political, social, religious, emotional, and economic implications and dimensions of growing old in times of profound insecurity, as well as examine the ethical challenges and possibilities that aging might presuppose in such a global context.

Acknowledgements

I want to specially thank Katie Kilroy-Marac for the generosity and care with which she has supported this collection. I am also grateful to Paige Edmiston, Aaron Su, Dima Saad, and Melanie Ford for their incredible work as editors, reviewers, and webmaster. Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to all the contributors’ of this collection and their outstanding work.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Allison, Anne. 2013. Precarious Japan. Durham: Duke University Press.

Barrientos, A. 2003. “Old Age Poverty in Developing Countries: Contributions and Dependence in Later Life.” World Development. 31 (3): 555-570.

Buch, Elana. 2018. Inequalities of Aging: Paradoxes of Independence in American Home Care. New York: New York University Press.

Carbonaro, Giulia. 2024. “The oldest country in Europe: What is behind Italy’s aging problem?” Euronews.

Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico (CEPLAN) 2023. Cambios en la estructura etaria de la población.

Clark, Margaret. 1967a. “The Anthropology of Aging, a New Area for Studies of Culture and Personality.” The Gerontologist 7(1): 55-64.

Clark, Margaret.1967b. Culture and Aging: An Anthropological Study of Older Americans. Springfield: Thomas Books.

Cohen, Lawrence.1998. No Aging in India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Danely, Jason. 2014. Aging and Loss: Mourning and Maturity in Contemporary Japan. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Danely, Jason. 2022. Fragile Resonance: Caring for Older Family Members in Japan and England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fortes, Meyer. 1984. “Age, Generation, and Social Structure”. In Age and Anthropological Theory. David Kertzer and Jennie Keith, Eds. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fry, Christine. 1980. “Toward and Anthropology of Aging.” In Aging in Culture and Society. South Hadley: Bergin and Garvey.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). 2023. Situación de la población adulto mayor. Informe técnico.

International Longevity Center Japan. 2017. Aging in Japan.

Kauffman, Sharon. 1986. The Ageless Self. Sources of Meaning in Late Life. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Lamb, Sarah. 2000. White Saris and Sweet Mangoes: Aging, Gender, and Body in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lock, Margaret. 1993. “Cultivating the Body: Anthropology and Epistemologies of Bodily Practices and Knowledge.”Annual Review of Anthropology 22: 133-155.

Myerhoff, Barbara. 1992. Remembered Lives: The Work of Ritual, Storytelling, and Growing Older. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan University Press.

Robbins, Jessica. 2020. Aging Nationally in Contemporary Poland. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.United Nations. n/d. Global Issues: Aging.

Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori holds a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Michigan. Her work is located at the intersections of old age, care, and precarity.

Cite as: Zegarra Chiappori, Magdalena. 2024. “Introduction”. In “Aging Globally: Challenges and Possibilities of Growing Old in an Unsettling Era”, edited by Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori, American Ethnologist website, 7 August 2024. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/collections/aging-globally/aging-globally-c…egarra-chiappori/]