by Gabriela Manley

Does COVID-19 need an introduction? Perhaps – for the future generations, and those still hiding in their Y2K bunkers

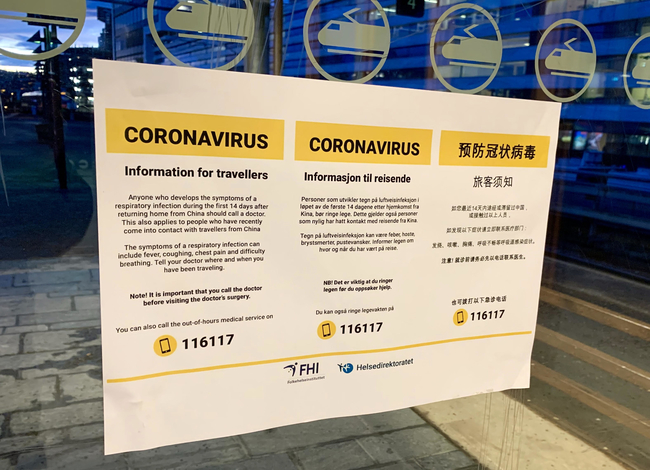

First detected late 2019 in the Wuhan province of China the novel coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 disease began to make headlines around the world, quickly becoming the top news story as the virus slipped through initial containment measures, beginning its inexorable spread around the world. On March 11, 2020, after what many considered to be much dithering, the World Health Organization officially declared the virus a global pandemic. The move was surprisingly anti-climactic. With over 100,000 cases world-wide and 3,400 deaths at the time of the declaration many had already been referring to it as a “pandemic all but in name.” Panic buying toilet paper had already become a worldwide phenomenon, and Italy and Spain where beginning to introduce tough quarantine measures as they struggled to contain the virus. The pandemic has now triggered global containment and quarantine measures of unprecedented scale disrupting the way that we work, socialize, and think globally for many months to come.

The virus has now forced us to fundamentally shift every aspect of our lives, causing disruption across both global and personal scales. As borders shut down, quarantines are enforced and the world comes to a standstill, what is there to gain from an anthropological engagement with the virus? The Pandemic Diaries essay collection seeks to explore this question through a series of rolling essay installments, each of which will aim to address some of the most pressing issues at the time. Edited by the in-house AES team of Gabriela Manley, Bryan M Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, our hope is to challenge us to critically reflect on our experience of the virus from a number of different perspectives, all of which have significantly disrupted our lives as anthropologists, as academics, and as members of society. Crucially we seek to ask, what are the themes we should be exploring, and questions we should be asking in these times of deep disruption?

For anthropologists, perhaps the most drastic disruption has come with the closure of universities and enforcement of social distancing rules. As anthropologists, our work takes us all around the world and demands a high level of close social interaction with our informants, their daily lives, and routines. This long-term face-to-face ethnographic work so critical to our discipline is now under serious threat from a pandemic which is shutting down borders and forcing us to isolate form the world around us. As I write this (March 23rd), my university has sent out an email to all Anthropology staff and PhD researchers: we are to terminate all face-to-face fieldwork immediately and indefinitely. Pre-fieldwork PhDs are to cancel their fieldwork plans, and those currently in the field are to return home. Similar disruptions can be seen around the world as PhD researchers find themselves quarantined in their field or flying home to flee the virus, uncertain of how or when their research may resume. This sudden disappearance of planned presents and futures leads to a deep sense of disruption in the personal linear narrative of our life (Becker 1997) – especially when this disruption is to the otherwise meticulously planned timeline of a PhD. Many will now be grappling with the indeterminate future that has opened up before them; from cancelled visas, void funding, or facing the choice of spending the pandemic in the field or with their families. The first installment of these Pandemic Diaries is dedicated to them, and their stories of disruption.

Closer to home, patterns of everyday life are also being disrupted, forcing us to dramatically adapt and re-think our work as anthropologists inside the classroom. As universities shut down and teaching staff scramble to adapt their courses to online formats, what shifts other than the location of our work? And how will this shift change the way we relate to work, students and faculty? Teaching staff find themselves caught between feelings of duty towards their students and calls to resist the expectation of courses being perfectly adapted to online teaching within a matter of days. When classroom-based, face-to-face teaching is the heart of what we do, what is lost (and gained) from this switch to online teaching?

These disruptions also bring with them the personal struggles associated with working from home. With no one to rely on them and no one to depend on, those who live alone now face the challenges of becoming entirely self-motivated and self-efficient as they battle through isolation and loneliness. In contrast, those who have families to attend to are faced with the prospect of work and family life clashing daily, and indefinitely. With schools closed and social isolation in place, daily work routines become a careful balancing act of care, work, teaching (both students and for many parents their own children), and family life. Disruption of work begins to overlap with the disruption of every other facet of life. Since social isolation began, we have seen hundreds of “coronavirus time-management” schedules posted online, some ironic, some serious, but all in some way trying to make sense of the new ways in which we must temporarily manage our time. How is time re-arranged in these highly communal, or highly isolated times? How are work and home life negotiated when they share such close quarters? For the last few days I have not been able to stop thinking of that famous BBC Skype interview, in which the male respondent’s young daughter burst into the room, chased by a flustered looking mother. At the time, it was noteworthy enough to make the news around the world, and sparked heated online debates on race and gender roles in the household. Is this to become our new normal? And if it is, will it have a lasting impact on our relationships with family and work? What sort of inequalities – gendered or otherwise – are being reinforced and reproduced by working from home? How will loneliness and isolation affect the work-life patterns of those who face quarantine alone? And, what kind of new and emerging pressures will come from both these time management challenges?

In a time of crisis, our perception of time itself is disrupted (Knight 2016). It can become bloated with an endless escalation of information as we continuously refresh the breaking news, watching the number of cases ticking up and up, with no respite in sight. It can become elasticized, stretching as we wait in anticipation for disaster to strike (Knight and Stewart 2016), and it can snap into acceleration as the crisis suddenly worsens. As my own social isolation is underway, the endless days to come yawn ahead of me, filled almost exclusively with the constant chatter of the BBC News channel that is now permanently on. Time threatens to become meaningless as the days all blend into one whilst I wait for the indeterminate future to crystalize. I obsessively call home to my parents living in Madrid, and their own timelines merge with mine. The UK’s contagion is two weeks behind that of Spain’s and Italy’s, and as I talk to them about Spain’s ruthless quarantines and skyrocketing death rates their present becomes my future – they send a warning from this future: it’s coming. What other crisis-driven experiences of time are affecting us? And how do they differ in relation to our isolation circumstances? Importantly – how can our engagements with time and crisis help us make sense of what is going on around us?

On the more sinister side of things there has also been widespread concern about the haste in which these measures are having to be implemented, forcing us to upload content to online platforms without scrutinizing copyright and privacy policies. I have heard colleagues and union members angrily refer to the shift to online teaching as “Project Panopticon,” expressing genuine concern at the copyright and surveillance implications that recording and uploading lectures might have if terms and conditions are not appropriately scrutinized. Which social and structural issues should we as anthropologists be paying close attention to in these times of disrupture?

Naomi Klein has already alerted us all to the dangers of disaster capitalism, which creeps in unnoticed during times of radical disrupture. She uses the term Shock Doctrine to describe the brutal tactics of using the public’s disorientation following a collective shock to push through radical pro-corporate measures. Hurricane Katrina, the 2008 financial crisis, and the Iraq war are but a few examples of times in which anthropologists have had to critically engage with the “extraordinary politics” phenomenon being used to rush through the corporate wish-list. This might serve us as a much-needed reminder of all that might fall through the cracks as our attention is fervently focused on the global pandemic. With the coronavirus disrupting social and economic lives at an unprecedented global scale, who are those who are most likely to be left behind? As anthropologists, what and who are we worried about in these uncertain times?

Of course, as we grapple with these issues both in the Pandemic Diaries series and in our day to day lives, it’s important to remember that rupture (or disrupture) can also open up spaces of creativity and change (Holbraad et al 2019) that we must also attend to. All around the world we have seen heartening gestures of community support, from Italians playing music from their balconies to volunteer services that are set up to help the most vulnerable in our society. In Spain, private hospitals have been seized by the government and temporarily re-nationalized; in the USA there has been a considerable surge in positive attitudes towards Medicare for all; and here in the UK Universal Basic Income has been considered by the government, something unthinkable only a few weeks ago. In anthropology, Anthrodendum’s Covid-19 online teaching collective, organized by Paige West and Zoë Wool, is changing the way that we share knowledge and academic support. The spaces that open up in the immediate aftermath of (dis)rupture, offer us room to change, adapt, and innovate – even experiment outside of our usual constraints. These are spaces of momentary change and innovation that although fleeting, may have lasting consequences we should not ignore. To this end, we must also ask ourselves how is this space innovating, creating, and changing? How are our status quos being disrupted? And how are these creative spaces helping us imagine how to do things differently?

Becker (1997) reminds us that “continuity is an illusion. Disruption to life is a constant in human experience.” Yet the coronavirus pandemic does not feel like normal disruption. It has become a disruption of the most unspeakable proportions, affecting almost everyone in the world in almost every way imaginable. It has disrupted at a national level, at a personal level, at an intimate level. The Pandemic Diaries series seeks to capture this moment of historic disruption and help us make meaning of the world around us. It hopes to be a space of anthropological reflections and ethnographic engagements in which anthropologists may freely explore the many ways in which our life is being disrupted by the virus. The topics discussed are but a handful of ways in which life has had to change in the past weeks, and yet many more challenging changes lie before us as the virus continues to spread. It is because of this that we have decided to make the Pandemic Diaries a rolling set of publications, adapting week to week to the fast-changing world around us. We hope these engagements will help our contributors as well as ourselves and our readers to finding some meaning in chaos – to think critically and ethnographically about the strange and transformative moment that we find ourselves in.

References:

Becker, Gay. 1997. Disrupted Lives: How People Create Meaning in a Chaotic World. Berkeley: University of California Press

Holbraad, Martin., Kapferer, Bruce., and Sauma, Julia. F. 2019. Ruptures: Anthropologies of Discontinuity in Times of Turmoil. London: UCL Press

Knight, Daniel. M. 2016. Temporal Vertigo and Time Vortices on Greece’s Central Plain, The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 34 (1): 32-44.

Knight, Daniel and Stewart, Charles. 2016. Ethnographies of Austerity: Temporality, Crisis and Affect in Southern Europe, History and Anthropology, 27(1): 1-18

Cite As: Manley, Gabriela. 2020. “Introducing the Pandemic Diaries”, In “Pandemic Diaries” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, March 27 2020 [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/introducing-the-pandemic-diaries]

Gabriela Manley is a final year PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews studying the futural imaginations and orientations of the Scottish independence movement