When I began a kind of “pedagogic” journal at the start of this academic term, I envisioned its pages slowly expanding as I filled it with my amateur drawings, written reflections, salvaged objects, and photographs inspired by and collected during the course of my teaching. Teaching a class that requires the students to produce a reflexive journal, I wanted to participate in this experimentation with different ways of “growing into knowledge” at the intersection of art and anthropology (Ingold 2015). I took my journal with me to classes and teaching workshops, tucked into my bag or pilled with handouts, ready to add to it during an activity or immediately afterwards. I looked forward to adding some small note or sketch or object to my journal as a time to reflect on my teaching and engage in the same practice as my students.

However, since the university announced that we would not be resuming face-to-face teaching after the spring holidays due to Covid-19, I have regularly found myself staring at the brown journal on my table. It seemed at odds with the new, digital world I found myself hurrying to assemble for teaching. It appeared to ask me too bluntly to confront this radically different new world of teaching and interacting. Embodied experiences no longer seem to hold a place in the world we are now inhabiting, in which conducting a group dérive or visiting the university archives to examine photographs is no longer possible. Attempting to continue to fill the journal’s pages not only seemed futile now that the practical elements of teaching had been curtailed, but it also seemed an intensely insignificant thing to be concerned with at a time when millions of people are facing crisis. Knowing how incredibly fortunate I am to have a safe place to live with a sense of security, unlike so many people facing incredibly challenging, uncertain, and lonely situations around the world, I felt that to draw (and badly at that), to jot down personal reflections on teaching and learning, to stitch and stick was a frivolous use of my time.

After the announcement for the ‘shift online’ was made there was suddenly a flurry of activity in order to ensure that teaching could resume in an entirely remote, online format after the spring break. We were lucky that we had two weeks to prepare, unlike the staff at many institutions who had but a day or two, but still it felt like a large, urgent, and complex task. I, and many of my colleagues, raced to download the necessary software, read-up on its functionality, evaluate whether assessments needed to change, figure out how content would be delivered and determine if and when real-time classes could be held. The remainder of my time became filled with regularly contacting friends and family, figuring out how I and my partner (who works in the USA but is unable to return there after visiting the UK for what was meant to be just a ten day trip) can effectively work at the same small kitchen table, making periodic trips to the supermarket, and continuously reading the news.

The first week of preparation therefore whirled by in a flurry of activity and a constant stream of communication with colleagues, whether over video conference or email. However, as arrangements began to fall into place, we all became accustomed to new patterns of work and settled down to writing or recording lectures in order to be uploaded online, I found myself feeling disconnected. Having only started my current post in January, I am still new to both the university and the place I’m living more generally so my social networks are still very much in their infancy and my understanding of the workings of the whole university by no means complete. Despite the enormous efforts made by colleagues to maintain contact, offer support and preserve a sense of community, the ‘shift online’ left me concerned about feeling ‘part’ of my department at a moment when I was just starting to feel settled. There were no longer opportunities to say hello to students in the corridors or ask a quick question to a more experienced colleague or listen to departmental seminars with colleagues and students alike.

Throughout this period the journal was left closed on the coffee table, its as yet unfilled pages pressed tightly together. If “drawing is movement into the world” (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2015, 260), what place does it hold in a time when we must limit our ventures outside? As noted by Ingold, “the passenger’s concern is literally to get from A to B, ideally in as short a time as possible. What happens along the way if of no consequence and is banished from memory or conscious awareness” (Ingold 2010, S127). If drawing, like walking, is a crucial form of “wayfaring” and knowledge production (Ingold 2015), how can we continue to find our way, to teach and learn when confined to online encounters and to moving only as a “passenger” between fixed points of ‘A and B’? These were the questions I began asking as I looked at my journal. But they were also questions which palled in significance as I hit refresh on the news feed on my phone each day. And so, I refused to engage with the questions prompted by my journal in any substantial way, feeling very intensely the more pressing issues being faced by others, including some of my colleagues and students.

My journal closed on the table

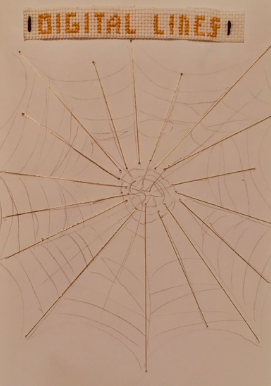

A week into online teaching delivery, however, I picked up my journal again for the first time. Whilst typing away at my laptop I suddenly caught the journal in the corner of my eye as I had done so many times over the past couple of weeks. This time, however, I felt compelled to pick it up and add to it – to draw and write and stitch in an attempt to make sense of the changes educators and students alike are currently facing, and to feel a tangible, embodied connection to the material I must now deliver online, and to the conversations I am now having with students over video-conferencing or text threads. In a context in which observation—looking out at the world from my window, reading student discussion threads, watching the news with grim anticipation—seems to be an increasingly dominant part of my day-to-day life, I find myself desiring more than before the possibilities afforded by drawing as a form of “wayfaring” that can “reconnect observation with participation” (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2015, 259). In a time when uncertainty reigns, I find myself drawn to draw in an attempt to make sense of this uncertainty. And so, I tentatively picked up my pencil and my needle and resumed my journal.

A page of stitching from my journal

The compulsion to resume my journal was in large part, I believe, spurred by the uplifting things I began to notice as I read the news each day, or things I saw as I ventured out for periodic trips to the supermarket, or things I heard when speaking with friends, family, colleagues, and students. These stories all seemed to share an effort towards creativity, towards making something and connecting with other people; whether in the case of children drawing rainbows and pasting them in windows, people taking up knitting and painting, musicians giving online concerts, or the appearance of resourceful cooking podcasts. People seemed to be finding new ways of drawing lines of connection and seeking out embodied creativity.The entries that I have begun making into my journal in this new pedagogic landscape are, and will undoubtedly continue to be, different. It is growing into a profoundly more personal document which now includes reflections on my own anxieties and elements taken from the news, woven into records of experiences and thoughts around teaching online. And I continue to be deeply aware of the privileged position I am in to be able to pursue this activity. But through resuming this journal, I have found that continuing this practice and pursuing embodied, creative acts (however small) alongside my online teaching has become crucial to helping me maintain a tangible connection to, and sense of consistency within, my pedagogic practice.

There are numerous challenges to the ‘switch online’ for educators. Not least trying to find times when everyone can participate in discussions when we are spread across the world and many are facing additional caring responsibilities. But as we look ahead to an indeterminate period of teaching (and interacting more widely) online, I have found an unexpectedly productive, positive outcome of keeping a journal of drawings, writings, stitchings and pastings.

I find in my day-to-day life and teaching within this new landscape that small acts of embodied creativity and connection are more vital than ever before as a counterbalance to the ‘shift online’ and the sense of disconnection, uncertainty, and ephemerality that it engenders. I don’t seem to be alone in seeking out these kinds of small, tangible acts and as I encounter more examples of peoples’ creative efforts to maintain connection and embodied experience, I feel less isolated, less disconnected from my teaching, and drawn into a wider community of creative practice.

References:

Grimshaw, Anna and Amanda Ravetz. 2015. “Drawing with a camera? Ethnographic film and transformative anthropology.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21: 1467-96

Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Oxon: Routledge

Ingold, Tim. 2015. The Life of Lines. Oxon: Routledge

Cite As: Stevenson, Emily. 2020. “Creativity and Embodied Practice during the ‘Shift Online’.” In “Pandemic Diaries,” Gabriela Manley, Bryan M. Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, eds., American Ethnologist website, 16 May 2020 [https://americanethnologist.org/features/pandemic-diaries/teaching-right-now/uk-creativity-and-embodied-practice-during-the-shift-online]

Emily Stevenson is Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the University of St Andrews.