The anthropological scholarship on rumors tends to focus on their role as emergent and propulsive in times of political and social disturbance, with the potential to be instrumentalized to perpetuate violence against those who are its objects (Bubandt 2008; Das 2007; Guha 1999). In contrast, this essay explores rumors within the context of environmental crises and natural disasters to show that they may engender indifference. I treat rumors as diagnostic of our current condition of living on an increasingly volatile Earth. Yet rumors’ potential for engendering indifference may also promote a more ethical relationship to our plights in the Anthropocene.

These insights arise out of an unusual rumor that troubled my aunt and me this summer. This rumor has a long back story. The Japanese comic book, The Future I Saw, published in 1999 by the manga artist Ryo Tatsuki, centers on premonitions Tatsuki received in her dreams. The comic garnered immense public attention after it was discovered that it correctly predicted the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11, 2011. A 2021 reprint of the comic predicted that another massive earthquake was to take place on July 5th, 2025, along with a tsunami three times higher than that of 2011. The rumor went viral on the internet and unnerved peoples across East Asia. The rumor circulated extensively over social media online and is estimated to have caused a staggering 3.9 billion dollars of economic loss and unprecedented transnational impacts to the East Asian tourist industry.

A predictive astrologer gives a consultation

The rumor made its way to my family in Macau. In June 2025, when I was attending the School of Criticism and Theory at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, I received an urgent text message from my mother: “I know you are in America, yet your aunt is very worried about the Japan earthquake rumor and wonders if it would affect Macau. She asks me to consult you to cast an astrological chart for her. Could you do that?”

Here, a confession is warranted: besides my academic research on Asian American literatures and affect studies, I am also a practicing astrologer specialized in horary astrology, a predictive astrological technique that aims to provide concrete answers as prediction based on the querent’s inquiry. Unlike the popular Sun-sign astrology in vogue since the mid-20th century that combines personality analysis with self-help therapy, horary astrology, or “the astrology of the hour,” traces its lineage from Hellenistic times. It was popularized in Medieval periods and later syncretized with predictive techniques from Arabic astrology and European Renaissance traditions (Brennan 2020; Lilly 2005 [1647]).

A divinatory tool, horary astrology is propelled by questions of the moment that have spontaneously arisen within the attuned psyche of a “querent” (literally, the person who asks; the term also indicates the person who seeks guidance). The question is put to the astrologer, who casts an astrological chart reflecting the sky of the here-and-now based on the querent’s inquiry. This chart is the birth chart of the question itself, showing all the planetary coordinates at the moment the question emerged in the mind of the querent. It is believed that the more invested the querent is in the inquiry, the more aligned the planets will be, allowing the astrologer to interpret the intricate astrological symbolism within the chart, thus yielding a more accurate prediction.

At the time I received my mother’s text message, I found myself quite indifferent to this question for its seeming irrationality. How could this alleged disaster possibly affect Macau, which is approximately 1800 miles away from Japan? How likely is Macau to ever experience earthquake, given that it is not located on the intersections of any tectonic plates? Furthermore, given the fact that I was physically continents away and twelve time zones behind Macau, such worries of an earthquake did not feel like a concern of mine.

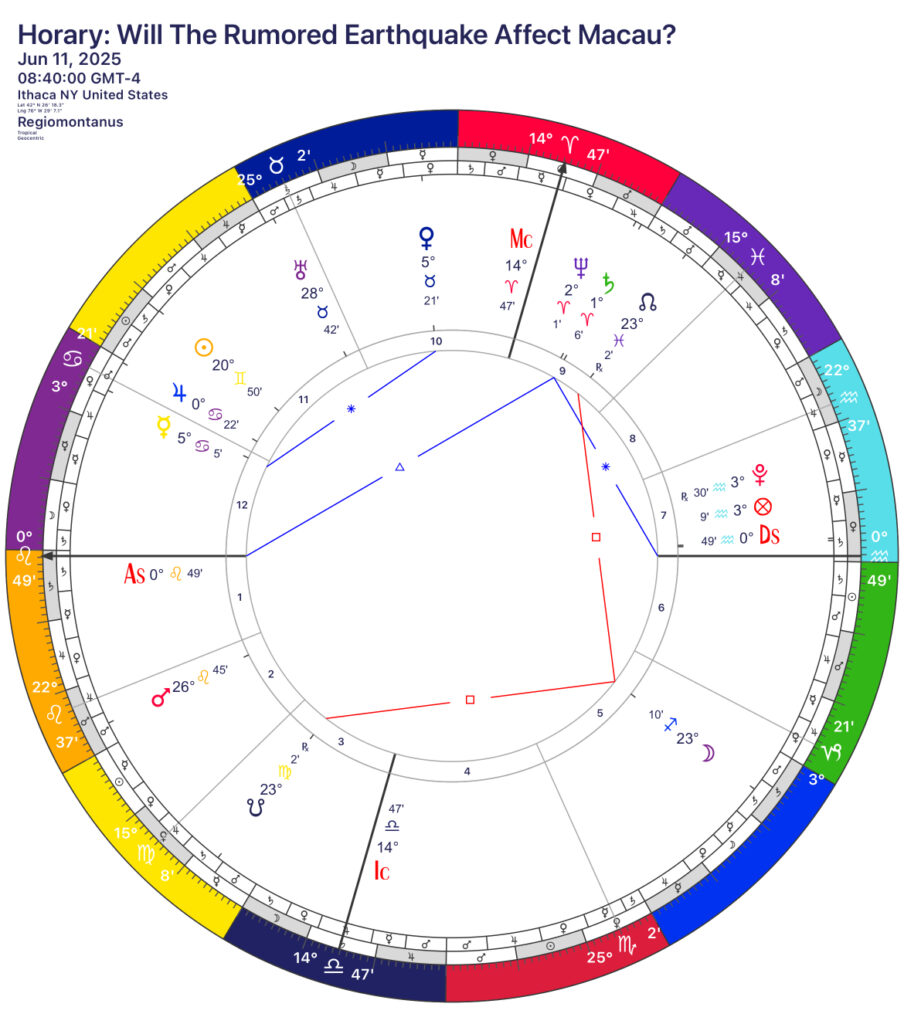

Nevertheless, out of familial obligation, I cast a chart for the moment and gave the following reading: neither the planetary significators for the querent nor Macau in general were afflicted by any malefic planets or in unfavorable positions within the chart. The moon, which symbolized the overall course of events, was not severely obfuscated or harmed in the near future. No other alarming planets were to be found along any relevant axes. I thus judged that no imminent danger was posed to my aunt or Macau. My aunt was very pleased with my answer.

Astrological chart for the rumored earthquake of July 2025. Image by Kam Tou Pang.

In this essay, I am not interested in debunking doomsday hearsay. Rather, I am fascinated by the fact that both my own indifference and my aunt’s worrying were distinct affective responses elicited by the rumor. Here I consider how these affects, or the lack thereof, bring us closer (or further) to one another as we live on an Earth whose dynamic processes feel off kilter from our own.

Indifference as a problematic

For our modern, rational minds, it is common to brush off manga prophecy as nonsensical, for science tells us that predicting earthquakes is a very difficult task and cannot be left to fantastical conjecture within comic books. People have been “disappointed” by failed doomsday prophecies throughout history, including the much-hyped apocalyptic myth of the Millennium in 1999 and the Mayan prophecy of 2012. Many regard those who still believe in such predictions as ignorant, if not outright idiotic. And yet, I suspect this widespread dismissal of prophesies runs deeper than just a dismissal of irrationality: it also stems from a more profound indifference.

Increasing natural disasters in the past decades have prompted contemporary thinkers to reassess the anthropocentrism inherent in the dominant narratives of the Anthropocene and to contemplate instead the dynamic Earth in its own right, aside from the humans living on it. Environmental humanities scholar Nigel Clark highlights the indifference of the natural world toward humanity:

Without our species, the earth would still pulse with life and the sun would pump out light and heat, heedless and unperturbed. This is the bottom line of human being: we are utterly dependent on an earth and a cosmos that is, to a large degree, indifferent to us (2011, 50, emphasis added).

Clark identifies a “radical asymmetry” between the overwhelming might of nature and its potentially destructive forces vis-à-vis the infinitesimal interventions by human beings (2011, 30). Other scholars, such as Mick Smith and Jason Young, echo Clark in concluding that the Earth does not really care about us and has no “final purpose in a Kantian sense” (2022, 32). The Earth does not strive toward a teleology in service of human progress.

The Earth’s indifference to humans is simply a matter of fact. Nonetheless it strikes me that my own indifference towards the rumored earthquake, which if it had been true would have meant a tremendous loss of lives and widespread suffering, may be seen to echo this indifference of the Earth towards humankind. This emotional detachment towards a potential future may constitute a type of symmetry with the Earthly apathy. But what are the stakes of a human inhabiting that kind of indifference?

Indifference reigns when the danger feels distant. In my case, for instance, being far from Macau gave me a convenient out from having to take on board the rumor of this earthquake threat. I felt indifferent to it. Even though Clark reminds us that humankind is “vulnerable to being swept away” by the “exertions of the earth and the cosmos” (2011, xii), the reminder of our vulnerability does not register when it is an abstraction or articulated in the future tense. Rather, vulnerability appears only to be felt when we are experiencing it in the here and now, or when we have experienced it in the recent past. The sense of our vulnerability eludes us.

In the context of a lively Earth and its various communiques to us, our indifference may be seen as a willful ignorance of our own vulnerability or an exhaustion with its pervasiveness. Either way, something of this indifference strikes me as unethical, a disregard for the matter in question, an absence of care, perhaps a numbed and numbing orientation to what might be.

Worrying in the face of disaster rumor

Instead of indifference, is it possible to “feel” for potential disasters in a more ethical way? Take my aunt for example: a middle-aged Chinese woman living in Macau who devotes herself to family and frets over this alleged earthquake threat. Putting aside the fact that she was giving undue attention to a rumor, aiding in its perpetuation and potentially harmful effects, might we see her worrying as arising from a deep, emotional investment in the world in its earthly dimension? Might we see her evincing a keen “atmospheric attunement” (Stewart 2011, 445) to the Earth?

For my aunt, the rumor may have become the disaster already, given that, as anthropologists of rumor have postulated, the infectious nature of language within the rumor instantiates “things to happen almost as if they had happened in nature” (Das 2007, 119). Analyzing the psychological effects of rumor, Robert H. Knapp has claimed that rumors “express and gratify the emotional needs of the community” (1944, 23, emphasis in original). The act of passing on rumors helps externalize repressed fears, wishes, and hostilities, which can even be a cathartic experience (Knapp 1944, 34). From this perspective, taking rumors of purported natural disasters seriously can be understood as tapping into one’s latent emotions regarding one’s own mortality. For individuals, partaking in disaster rumors provides an occasion to confront existential insecurity. Being made into a worrying subject by a rumor may be to care and feel life deeply.

I posit that such worrying and taking steps to attend to such worries, far from being irrational or rumor mongering, may be a more appropriate response to our present of extreme weather events and environmental catastrophes, when widespread indifference and a sense of powerlessness easily descends into nihilism. Through her act of worrying, my aunt brings this abstract category of natural disaster within the ordinary, reminding herself and me of our corporeal vulnerability as subjects of a volatile Earth. Certainly, I am not proposing that worrying is the solution to all our collective problems, for excessive consternation can also lead to paranoia. But the activation of the mode of worrying may be the beginning of an ethical response to baleful environmental change: to stay attuned, to get involved affectively, to not be the cold, cynic skeptic but to genuinely care, listen, and take action.

Also notable is that for my aunt, it is not science but predictive astrology that makes this disaster real (or unreal) to her. It is the spurned occult practice that restores a gap between the ordinary and the extraordinary, similar to the dream premonitions Ryo Tatsuki received that started the disaster rumor. Here, the astrologer helps make the potential disaster expressible and legible for the worrying querent (Favret-Saada 2015).

The fateful day of July 5, 2025 has now passed and the prophecy did not come to fruition. My aunt’s worry was assuaged twice over, first by my astrological reading and next by reality itself. Yet I am no longer as indifferent.

References

Brennan, Chris. 2020. Hellenistic Astrology: The Study of Fate and Fortune. Amor Fati Publications.

Bubandt, Nils. 2008. “Rumors, Pamphlets, and the Politics of Paranoia in Indonesia.” The Journal of Asian Studies 67 (3): 789-817.

Clark, Nigel. 2011. Inhuman Nature: Sociable Life on a Dynamic Planet. Sage Publications.

Das, Veena. 2007. Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. University of California Press.

Favret-Saada, Jeanne. 2015. The Anti-Witch. Translated by Matthew Carey. Hau Books.

Guha, Ranajit. 1999. Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India. Duke University Press.

Knapp, Robert H. 1944. “A Psychology of Rumor.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 8 (1): 22-37.

Lilly, William. 2005. Christian Astrology. Cosimo Classics Paranormal.

Smith, Mick, and Jason Young. 2022. Does the Earth Care? Indifference, Providence, and Provisional Ecology. University of Minnesota Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2011. “Atmospheric Attunements.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (3): 445–53.

Kam Tou Pang is a PhD candidate in Literary Studies at University of Macau. His research focuses on contemporary Asian Anglophone Literatures, Asian American studies, affect theory, queer studies, and travel writing.

Cite as: Pang, Kam Tou. 2026. “The Indifferent Astrologer and the Worrying Aunt in the Face of a Rumored Earthquake”. In “An Aesthetics for the End”, edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, 18 January. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/the-indifferent-astrologer-and-the-worrying-aunt-in-the-face-of-a-rumored-earthquake-by-kam-tou-pang/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).