“In 2004, the Canadian mining company Pan American Silver came to take over our lands, lands that we have inhabited for generations. It came promising improvements to our schools and houses, and also community development. But none of this happened […] In 2017, they proceeded to destroy our homes.” – (ex)resident of La Colorada, Zacatecas, México.

Mining activities have expanded rapidly in Mexico in the context of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), with devastating consequences for nearby rural communities and the environment in general. In a growing number of affected communities, locals have organized resistance to prevent the destruction and contamination of their territories, or at least to demand benefits and compensation. This article explores the conditions under which these struggles have emerged and proliferated.

In the five-year period leading up to NAFTA, most of the country’s state-owned mining assets were privatized, by selling them at below-market value and with little transparency to well-connected Mexican businessmen—most notably Jorge Larrea, owner of Grupo México; Alberto Baillères, the principal shareholder of Industrias Peñoles; Carlos Slim, whose emporium includes Frisco mining; and Xavier Autrey Maza and Alonso Ancira Elizondo, the main proprietors of Grupo Acerero del Norte (Cypher and Crossa 2024). In this way, powerful members of Mexico’s oligarchy acquired ownership of the country’s existing mining infrastructure and known mineral reserves, before foreign capital was unleashed to comb over old mining regions and explore new ones.

In 1992, changes were made to Mexico’s mining law to open the sector to 100-percent foreign-owned companies and to give preference to extractive activities over all other productive use of the land. In this context, Canadian-based mining firms took the lead in exploring for precious metals and soon began creating giant subterranean and open-pit mines throughout the country.

From 1994 to 2018, successive federal administrations—from both the Partido Revolutionary Institucional (PRI) and Partido Acción Nacional (PAN)—doled out more than forty-five thousand mining concessions to private companies, covering approximately 105 million hectares, equivalent to more than half the country’s territory. This was done without informing local communities and, therefore, in violation of the ILO’s Convention 169 concerning Indigenous rights, which Mexico ratified in 1990 (López Bárcenas 2017).

Under these circumstances, and in the context of rising global prices for metals and other primary commodities, foreign direct investment (FDI) began pouring into Mexico’s mining sector during the first decade of the new millennium, peaking in 2012 at USD 3.7 billion. Meanwhile Mexican mining firms invested even more: USD 36.9 billion between 2001 and 2015, compared to USD 23.8 billion in FDI during the same period (Azamar Alonso 2017, 153). Since 2015, private and foreign investments have continued to flow into the sector at near record levels, despite a slight decrease in 2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and despite President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s policy of not granting new mining concessions during his six-year term (2019-24).[1] In all, private investment in Mexico’s mining sector came to almost USD 5 billion in 2023, with more than two-fifths coming from abroad (CAMIMEX 2024).

Irrespective of its national origin, the mining capital operating in Mexico is integrated into global networks of logistical infrastructure, financial markets, and distribution chains. In this way, large-scale mines are planetary: they respond to signals from the world’s major stock exchanges and function as critical nodes in the configuration of global economic and political power (Arboleda 2020). With technological advances in artificial intelligence, big data, geospatial information systems, and robotics, these firms have expanded the extractive frontier in Mexico and elsewhere to low-grade reserves that require large amounts of water and energy to remove and process enormous quantities of metallic minerals.

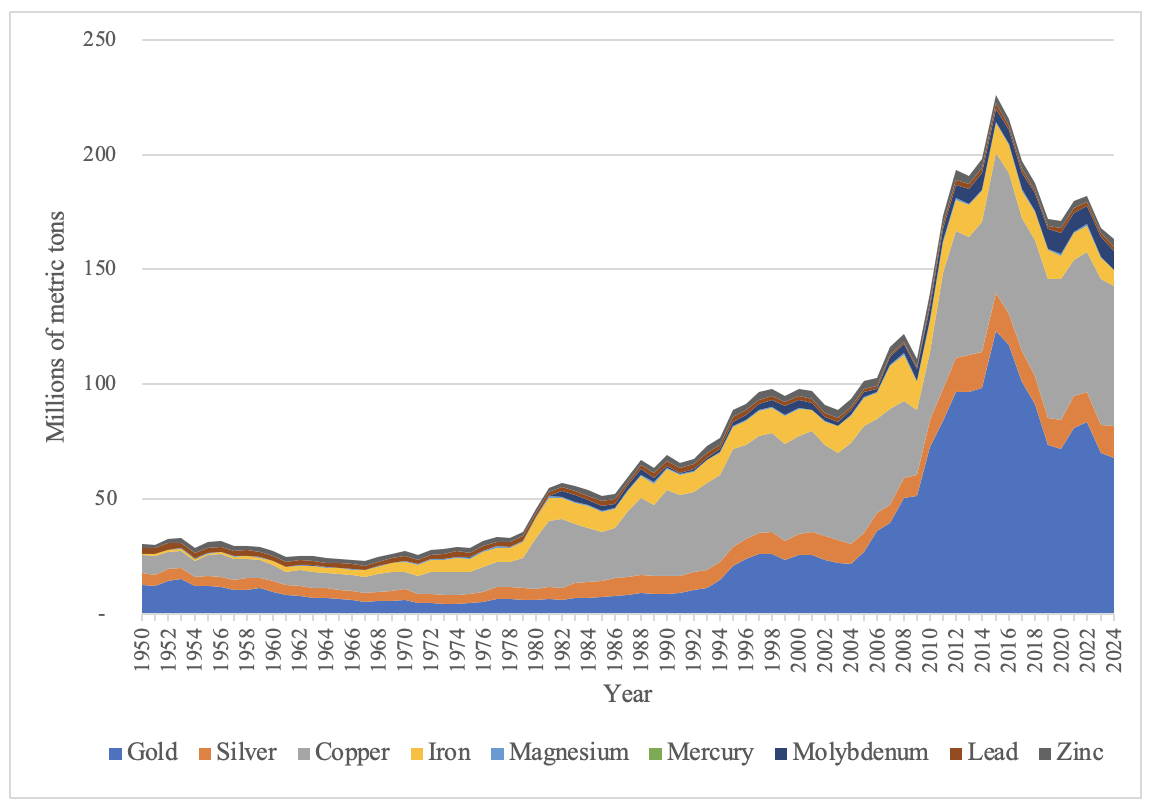

Figure 1 shows metallic-mineral extraction rates in Mexico between 1990 and 2024,[2] based on standardized procedures that include all materials that enter into economic processing, such as tailings, but exclude overburden (Eurostat 2001; 2018; Tetreault 2022).[3] As observed, these rates accelerated between 2005 and 2015 during a primary commodities boom, then began to decline as relatively high-grade ore reserves were depleted.

Figure 1. Rates of Metallic-Mineral Extraction in Mexico, 1990-2024

To be sure, the great acceleration between 2005 and 2015 shown in figure 1 reflects global trends (Görg et al. 2020). It is, accordingly, an indication of the degree to which Mexico’s economy has been further integrated into the world capitalist system, although in a distinct way, since more than 80 percent of its exports flow to the United States. This pattern of trade has been reinforced by NAFTA and, since 2020, by its successor, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Likewise, the most important foreign mining companies operating in Mexico, in terms of extraction rates, come from the United States and, even more so, from Canada—not only because of the advantages provided by these free-trade agreements, but also because of the proactive support of the Canadian government in promoting the interests of mining capital headquartered in its territory (Tetreault, 2019).[4]

Mining activities in Mexico responded to global market signals, including high metal prices between 2005 and 2012, driven by rapid economic growth in China and other BRICS countries, and more recently by a combination of increasing demand for minerals required for corporate-sponsored energy-transition strategies, financial speculation, and disruptions to the world economy caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Increasing material-extraction rates require territorial expansion and the appropriation of environmental resources and services. With the help of key state agencies—particularly the Ministry of Economy and the Agrarian Attorney General’s Office—foreign and domestic mining companies operating in Mexico have employed an array of tactics to dispossess peasant and indigenous communities of territory, symbolically significant landscapes, and healthy living environments, leading to the multiplication of social environmental conflicts (Tetreault 2022). On the one hand, mining companies offer gifts and monetary payments, promise employment opportunities and social-development projects, and generally create the illusion of prosperity and development; on the other, they pressure local agrarian leaders, threaten dissidents, and conceal the scale and seriousness of future environmental impacts.

Garibay (2010, 135) describes these dynamics as a “‘horizon of coercion’ that comes from governmental agencies, laws, courts, and political parties, who appear to local inhabitants as hired mining agents, pressuring them to give up land and resources, to sign leonine agreements, to accept small benefits, to convince them of a better future, and to threaten when necessary.” This is well illustrated by the experience of La Colorada, mentioned in the epigraph, where local inhabitants “remember having been called to a meeting with the state government, where they were pressured and intimidated to sign a document that favored the company,” in addition to “having been harassed and threatened by company directives.”

La Colorada mine, Zacatecas, Mexico. Photo credit: anonymous member of displaced community.

With this in view, it is not surprising that mining is the immediate cause of more socioenvironmental conflicts than any other activity in Mexico, according to three inventories. First, of the 218 socioenvironmental conflicts in Mexico recorded by EJAtlas at the time of this writing, 45 are associated with mining. Notably, only five began before the year 2000. Second, of the 560 conflicts included in the database created by Víctor Toledo and his collaborators at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, 173 revolve around mining projects. Finally, of the 336 conflicts around energy and mining detected in Mexico by the project Conversing with Goliath, 155 are centered on mining. Of these, 97 include demands for environmental protection and 36 focus on labor rights. Other demands have to do with territorial planning, pecuniary assets, corruption, insecurity, and organized crime.

Organized crime, violence, and hybrid forms of governance pose complicated challenges for organized resistance to extractive activities (Tetreault and Carmona Motolinia 2024). This is because criminal groups in Mexico have diversified their activities beyond the production and trafficking of illegal drugs by transforming themselves into “armed territorial actors” that “monopolize multiple criminal industries and become de facto rulers over local populations and territories” (Trejo and Ley 2020, 14). In this context, organized violence has served to weaken opposition to the expansion of extractive activities in Mexico (Paley 2015).

Not all struggles around mining seek to permanently block extractive activities, in accordance with the “environmentalism of the poor,” in which local inhabitants fight to defend territories and ecosystems that support traditional livelihoods (Martínez-Alier 2011). Some do, while others focus on negotiating greater compensation and better conditions for (at least part of) the directly affected population. For example, in the case of the forty-six families displaced by Pan American Silver’s large underground gold and silver mine in Zacatecas, “to this day they continue to fight for justice, and for them, justice implies having their lands returned to them and the closure of the mine” (Rodríguez Navarro 2021, 188).

Indeed, most conflicts around mining in Mexico involve struggles to definitively block extractive activities (Martínez Romero 2020), especially when the projects are still in their planning or initial phases (Paz 2014). But anti-mining struggles can change and adapt over time, as projects evolve. Further, positions of opposition, negotiation, and collaboration can coexist in the same territory, since the imposition of mining activities tends to create internal divisions in affected communities (Uribe Sierra et al. 2020).

In spite of all this, there have been success stories. For example, the Zapotec communities in the Sierra Juárez of Oaxaca have resisted the expansion of extractive activities and, as part of their struggle, have constructed postdevelopment alternatives, including community-based forestry and ecotourism, based on a system of local governance guided by the collective values and practice of comunalidad (Fuente Carrasco & Barkin 2011). There have also been partial successes—for instance, in the struggle against the San Xavier mine on the outskirts of the city of San Luis Potosi, where the Broad Opposition Front (FAO) prevented the historic town of San Pedro from being destroyed by Canadian-based New Gold’s open-pit gold and silver mine (Tetreault 2019).

Resistance movements to large-scale mining projects draw from a long history of peasant and Indigenous struggles in rural Mexico. In recent years, affected communities have formed networks of resistance at the regional and national levels, with support from civil-society organizations, university groups, and social activists. These collective struggles coalesced in 2008 with the creation of the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (REMA) and were further consolidated in 2011 by the establishment of the Mesoamerican Movement against the Model of Extractive Mining (M4), which brings together community-based and solidarity organizations from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, and Panama. In addition, Mining Watch Canada and other international solidarity organizations have provided various forms of support to anti-mining struggles in Mexico and beyond by collaborating with REMA, carrying out international awareness campaigns, and monitoring the actions of Canadian mining companies. The struggle against Pan America Silver’s mine in La Colorada, Zacatecas, is linked to these networks through the Observatory of Mining Conflicts in Zacatecas (OCMZac).

In conclusion, the expansion of mining in Mexico—rooted in neoliberal reforms, free-trade agreements, and increasing global demand for metals—has generated deep social and environmental fractures while reinforcing the country’s subordination to transnational capital. Yet, as this overview shows, mining has also become a powerful catalyst for eco-territorial struggles that draw on long-standing traditions of peasant and Indigenous resistance, now articulated through regional, national, and international networks. These movements not only contest dispossession and environmental destruction but also open pathways toward alternative forms of development and territorial governance based on collective rights, ecological stewardship, and community autonomy.

Notes

[1] This observation is based on an analysis of relevant data published in CAMIMEX’s annual reports, available online: https://www.camimex.org.mx/index.php/publicaciones/informe-anual.

[2] The differences between the statistics presented here and those in Tetreault (2022) are due to discrepancies in the presentation of data in the Statistical Yearbooks of Mexican Mining (Anuarios Estadísticos de la Minería Mexicana) published by the Mexican Geological Service (SGM). Starting in 2010, these data were published in two sections of the yearbooks (chapters 1 and 2), with some inconsistencies. This text is based on the statistics found in chapter 1, which coincide with those reported by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI).

[3] For readers unfamiliar with these terms, tailings are residual minerals left over after the extraction of metals from ore. Overburden refers to the layers of soil, rock, or other material that lie above a mineral deposit, removed during open-pit mining processes to access the ore below.

[4] Canadian companies operating in Mexico include: Agnico Eagle Mines, Alamos Gold, Argonaut Gold, Capstone, Equinox Gold, Excellon Resources, First Majestic Silver, Fortuna Silver Mines, Gatos Silver, Orla Mining, Pan American Silver and Torex Gold. Two of the most important US-based companies are Newmont and Coeur Mining.

References

Arboleda, Martin. 2020. Planetary Mine. Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism. London and Brooklyn: Verso.

Azamar Alonso, Aleida. 2017. Megaminería en México. Explotación Laboral y Acumulación de Ganancia. Mexico City: UAM.

CAMIMEX – Cámara Minera de México. 2024. Informe Anual 2024. Available online.

Cypher, James and Crossa, Mateo. 2024. The Political Economy of Transnational Power and Production . Mexico’s Metamorphosis 1983-2022. London and New York: Routledge.

Eurostat – Statistical Office of the European Union (2001). Economy-wide material flow accounts and derived indicators. A methodological guide. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

______ 2018. Economy-wide material flow accounts. Handbook. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Fuente-Carrasco, Mario and Barkin, David. 2011. “Concesiones forestales, exclusión y sustentabilidad. Lecciones desde las comunidades de la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca.” Desacatos 37: 93-110.

Garibay, Claudio. 2010. “Paisajes de acumulación minera por desposesión campesina en el México actual.” In Ecología política de la minería en América Latina: aspectos socioeconómicos, legales y ambientales de la mega minería. Edited by Gian Carlo Delgado. Mexico City: UNAM, pp. 133-181.

Görg, Christoph; Plank, Christina; Wiedenhofer, Dominik; Mayer, Andreas; Pichler, Melanie; Schaffartzik, Anke; and Krausmann, Fridolin. 2020. “Scrutinizing the Great Acceleration: The Anthropocene and its analytic challenges for social-ecological transformations.” The Anthropocene Review 7 (1): 42–61.

López Bárcenas, Francisco. 2017. La vida o el mineral. Los cuarto ciclos del despjo minero en México. Mexico City: Akal.

Martínez-Alier, Joan. 2011. El ecologismo de los pobres. Conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración. 5ª edición. Barcelona: Icaria.

Martínez Romero, Ulises Pavel. 2020. Continuo de conflictos megamineros en México: oposición y negociación en los casos de Cerro de San Pedro, Mineral de la Luz, Zautla y San José del Progreso. Tesis de Doctorado en Investigación en Ciencias Sociales, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Sede Académica México.

Paley, Dawn. 2015. Drug war capitalism. Chico: AK Press.

Paz, María Fernanda. 2014. “Conflictos socioambientales en México: ¿Qué está en disputa?” In Conflictos, conflictividades y movilizaciones socioambientales en México: Problemas communes, lecturas diversas. Edited by María Fernanda Paz and Nicolás Risdell. Cuernavaca and Mexico City: UNAM-CRIM / MAPorrúa, pp. 13-58.

Rodríguez Navarro, Grecia Eugenia. 2021. “Conflictos socioambientales en torno a la minería en Zacatecas, ilustrando el despojo.” Conflictos socioambientales frente al extractivismo y megaproyectos en tiempos de crisis multiple. Edited by Aleida Azamar Alonzo and Carlos Rodríguez Wallenius. Mexico City: UAM-Xochimilco, pp. 178-201.

Tetreault, Darcy. 2019. “Resistance to Canadian Mining Projects in Mexico. Lessons from the Lifecycle of the San Xavier Mine in San Luis Potosí.” Journal of Political Ecology 26 (1): 84-104.

_____ (2022), “Two sides of the same coin: increasing material extraction rates and social environmental conflicts in Mexico.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 24:14163–14183.

Tetreault, Darcy and Carmona Motolinia, José Ramón. 2024. “The materialization of El Zapotillo Dam in the Highlands of Jalisco, Mexico.” The Extractive Industries and Society 19.

Trejo, Guillermo and Ley, Sandra. 2020. Votes, Drugs, and Violence. The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uribe Sierra, Sergio, Gómez Alonso, Jorge and Tetreault, Darcy. 2020. “Dos conflictos mineros en Mazapil, Zacatecas: entre la oposición, negociación y la colaboración.” Región y Sociedad 32: e1373.

Darcy Tetreault is a political ecologist whose research focuses on extractivism, social environmental conflicts, and community-based alternatives in Mexico. He is the author of numerous articles on mining struggles, water governance, and development, and he has contributed to collective volumes on environmental justice and Latin American critical thought. His work has appeared in journals such as Latin American Perspectives and The Journal of Agrarian Change, as well as in edited books on extractivism and environmental conflict.

Cite as: Tetreault, Darcy. 2025. “Mining and eco-territorial struggles in Mexico”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/mining-and-eco-territorial-struggles-in-mexico-by-darcy-tetreault/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).