I

A warm spring night in Woodside, Queens, and no one is in sight on the sidewalks. But inside a venue on a deserted street, a crowd of Mexican migrant workers, mostly undocumented, chants “Culero, culero, culero,” as they wait for the last band in the lineup. It’s almost 1:00 a.m.; the trash bins are overflowing with empty Mexican beer cans. Inside, “el desmadre” reigns as Banda Bostik’s frontman, David Lerma (aka “El Guadaña”), walks onto the stage dressed in his usual black leather pants and vest. The crowd shouts “Culero, culero, culero!” to warmly welcome the rock band from Tlalnepantla, Estado de México.

El Guadaña thanks the crowd: “Banda, I know a lot of you fucking bastards are from Puebla. I don’t know if it’s true, but if you’re from Puebla, raise both hands so we can see you. But to tell you the truth, us chilangos[1] are the holy cock (la santísima verga).”

Someone in the crowd shouts at El Guadaña: “Start singing motherfucker” (Ponte a cantar culero). He responds calmly, “Wait, bastard” (Espérate cabrón), but they shout again, Pinche culero ponte a cantar.” With a smile, he replies, “Usted sáquese a la verga, culero,” then adds, “Banda, we’re here to bring back something you left behind—the rock and roll gigs from the neighborhood. Let’s imagine you’re in Mexico. This song’s for the true rockers of Mexico City.”

Since the 1990s, the sound of electric guitars and wild shouts—much like that night in Queens—has signaled a major transformation within the Mexican community in New York City: the arrival of Mexican teenagers from working-class neighborhoods from southern and central Mexico, including Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl in the Estado de México. Many shared a passion for rock music, and their migration was tied to shifts in the labor supply driven by NAFTA and market-oriented policies in Mexico since the late 1980s.

The first important change occurred when the pattern of adult male circular migration that had prevailed until the 1980s was disrupted in the 1990s by more dangerous and expensive border crossings, a consequence of U.S. border enforcement. This shift led to family reunifications and a new wave of young migrants from Puebla, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. Many of these teenagers entered the New York City school system or the local labor force. These young migrants, who had grown up listening to rock in working-class, semi-rural neighborhoods in Mexico, began creating their own music in New York and, in doing so, they changed the cultural production and consumption patterns among Mexicans.

By the 1980s and 1990s, a second shift took place as labor migration arrangements changed, leading to a new influx of migrants from urban areas east of the Mexico City metropolitan area, particularly from Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl (Neza) and the neighboring municipalities of Ecatepec and Valle de Chalco in the Estado de México. This shift brought significant cultural changes to the Mexican migrant community in New York. Over the next decade, the cultural life of Mexicans in “Neza York” was shaped by the rock music brought by migrants from Neza.

Behind this wave of urban migrant laborers were rising unemployment rates, wage declines, and the increasing cost of living in urban peripheries—conditions that, as Liliana Rivera notes (2008), first drove blue-collar workers to Mexico City in the 1970s, and later, in the 1990s, to New York’s migrant labor market. Within two decades, this population had entered a state of legal ambiguity as disposable workers. This massive flow and proletarianization gave rise to what some social commentators of the period described as a vibrant musical scene.

By the late 1990s, Gonzalo Aburto, co-host of the radio show La Nueva Alternativa, wrote in his column for El Diario La Prensa that the growing presence of “Latino” rock bands in New York was part of a “musical revolution experienced in many parts of the world” (Aburto 2000, 38).[2] The expanding Latin American migrant population in New York City fueled the rise of a market for Mexican rock bands, who began performing at iconic venues such as Roseland and Irving Plaza. This also sparked a cultural shift in the working-class neighborhoods where Mexican migrants settled, creating a new social figure: the Mexican roquero.

In 2001, journalist Amanda Cruz noted the transformation in the city’s music scene: “In the early 90s, local groups, venues, and Spanish-language concerts were practically nonexistent. Today, there are countless places to enjoy this vibrant music” (Cruz 2001, 42).

Figure 1. Rocking in East Harlem. Photograph by Claudia Villegas Delgado, used with permission.

II

As part of the so-called “musical revolution,” Mexican migrant rock formations emerged in three key locations. The first was East Harlem, or “El Barrio.” In the mid-1990s, Mexican DJs and sonideros from Ciudad Neza and the outskirts of Mexico City began organizing underground rock parties in rented basements, often ending in street brawls that attracted police attention.

The second location was Woodside, Queens, where the first rock shows by local Mexican migrant bands took place in neighborhood bars (barras) in the mid-1990s. The third was a basement on 9th Street in Brooklyn, where Los Esclavos (The Slaves) rehearsed.3 Formed in 1994, Los Esclavos, from Oaxaca, was one of the first Mexican heavy metal bands, and their rehearsal space quickly became a gathering spot for young Mexican migrants.4

Over the years, New York City witnessed the growth of Mexican rock—both in number and stylistic diversity—from punk to metal and ska. Migrants working as cooks, waiters, dishwashers, delivery workers, and construction laborers formed their own bands, performing across New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Boston, or California. Rock became a powerful means through which these migrants expressed their experiences of class exploitation and racialization as undocumented workers or as underclass citizens in both the United States and Mexico.

An illustrative example is the experience of migrants from the Montaña region in Guerrero. During Mexico’s economic crisis of the 1980s, many Mixteco families became poppy producers or day laborers in northwestern Mexico’s agribusiness sector. Faced with poverty and unemployment, many migrated to the United States, often leaving their children behind. These children later migrated themselves, and some turned to rock music as a way to address social inequalities on both sides of the border, as reflected in this song by Patarrajada:

Mira para arriba en la Montaña

Si miras fijamente ella no te engaña

Marginados, enfermos, indios patarrajada

Despojados de la tierra, ahora no tienen nada

Caminando distancias para ver un doctor

Los siglos han pasado y no se acaba el dolor

Cruzando las fronteras, perdiendo hasta la vida

Estadística más de la democracia jodida.

Look up at the Montaña

If you stare at her, she won’t deceive you

Marginalized, sick, patarrajada Indians

Dispossessed of the land, now left with nothing.

Walking long distances to see a doctor

Centuries have passed, and the pain still persists

Crossing borders, even losing their lives

Just another statistic in a fucked-up democracy.5

Every subaltern group has a history to tell (Binford 2016). Through Mexican migrant rock in New York, we can trace the transformation of regions such as La Montaña—from subsistence agriculture to poppy farming—alongside shifts in class and ethnicity through migration. This transformation was driven by drug trafficking, military violence, and the growing proletarianization of small Indigenous peasants (Hernández 2018). NAFTA further exacerbated these changes, particularly in rural Mexico. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Guerrero eliminated subsidies and rural banking, which devastated smallholders and allowed multinational companies to take over (Binford 2013). Amidst these upheavals, some teenagers turned to rock music as a way to express their lives as transnational proletarians.

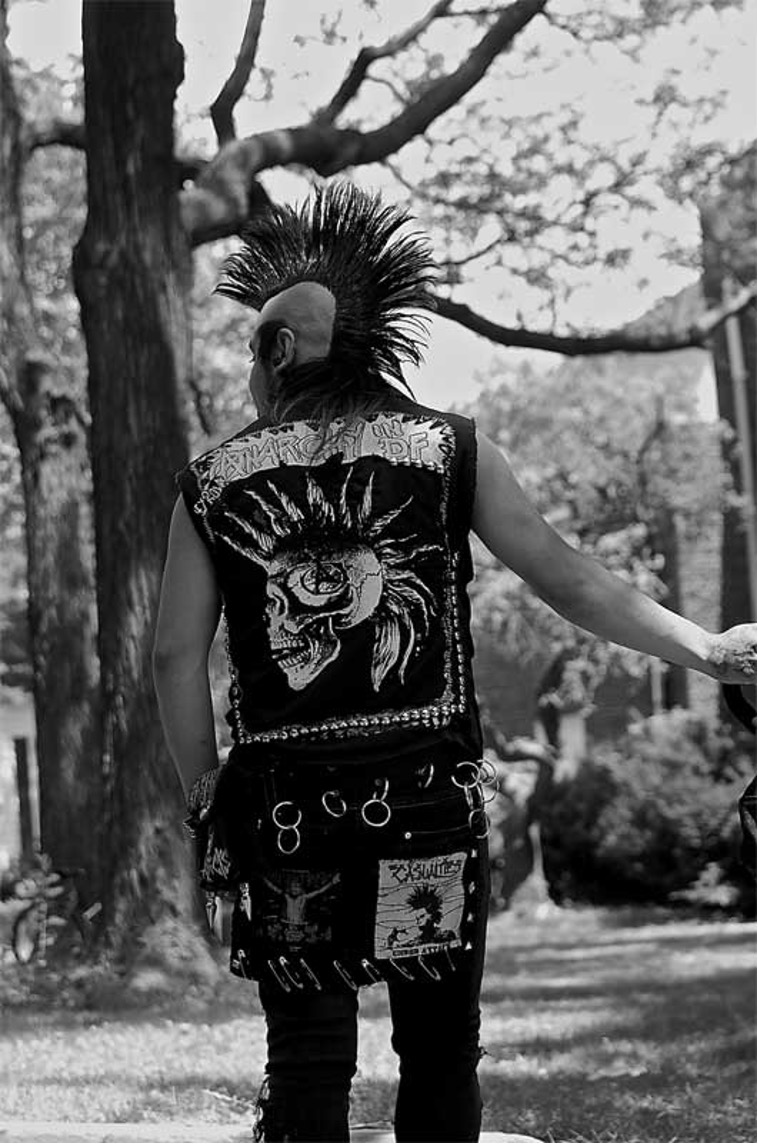

Figure 2. Anarchy in DF, Punk Island. Photograph by Claudia Villegas Delgado, used with permission.

Figure 3. Mr. Fuss. Photograph by Claudia Villegas Delgado, used with permission.

In its role as a longstanding supplier of labor to the U.S. labor market since the early twentieth century, NAFTA opened a new round of Mexican labor migration. Among the latest generation of Mexican workers, rock was part of their structure of feeling, particularly among teenagers. As they grew up and became workers, rock music conveyed their experiences, views, and social locations as Mexicans, migrants, and workers in New York City, as part of a broader process of class formation. After more than thirty years, Mexican rock in the city expresses the tensions between the forces that shaped the labor supply structure in North America and the agency of workers who are culturally shaping their class experience.

Notes

[1] A word referring to people from Mexico City.

[2] Gonzalo Aburto is a writer, journalist, actor, and activist from Mexico City. He has worked for various media outlets, including The Village Voice, La Jornada, La Prensa, Latina Magazine, Univision, Telemundo, CNN, and NPR. He has lived in New York City since 1986. As a journalist for Alternativa Latina (WBAI), he covered the AIDS crisis in the Latino community and, through his activism with ACT UP’s Latino Caucus, helped shape awareness and policy. He later served as editor of POZ in Spanish.

[3] The name reflects the shared grievances of many Mexicans about their position within the labor structure as migrants.

[4] Basements are key spaces in the settlement of Mexicans in New York City, serving as social and symbolic sites for their political and cultural experiences. Political organizing, for example, has involved committees of Virgin of Guadalupe devotees in New York churches, or solidarity groups supporting the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.

[5] La Montaña. Patarrajada. Album: Mi calle. 2007.

References

Aburto, Gonzalo. El Diario La Prensa. “Alterlatino: Algunas de las actividades más importantes del año 2000.” December 8, 2000.

Binford, Leigh. Tomorrow We’re All Going to the Harvest: Temporary Workers Programs and Neoliberal Political Programs. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

———. The El Mozote Massacre: Human Rights and Global Implications. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016.

Cruz, Amanda. El Diario La Prensa. “El rock en español apoderándose de Nueva York.” March 23, 2001.

Hernández, Rodolfo. “From the Montaña to the City: A History of Proletarianization of Mixteco Indigenous from Guerrero, Mexico to New York City.” Dialectical Anthropology 42, no. 2 (2018): 179–91.

Rivera, Liliana. “El eslabón urbano en el trayecto interno del circuito migratorio Mixteca-Nueva York-Mixteca: Los migrantes de Nezahualcóyotl, Estado de México.” In La migración y los latinos en Estados Unidos: Visiones y conexiones, edited by Elaine Levine, 53–73. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2008.

Rodolfo Hernández Corchado is an anthropologist from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He teaches ethnographic methods, oral history, and Marx’s Capital at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México. Rodolfo is currently working on two books: En las entrañas del monstruo: An Oral History of Víctor Toro: The Political Life of a Chilean Exiled Founder of the MIR and Mexican Labor Migration and Rock Formation in New York City. His work has appeared in Dialectical Anthropology, Íconos, and other publications.

Cite as: Hernández Corchado, Rodolfo. 2025. “Mexican rockers and proletarians in New York City”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/mexican-rockers-and-proletarians-in-new-york-city-by-rodolfo-a-hernandez-corchado/

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).