The Mural Zapatista, created in 2001 in New York City’s El Barrio, can be regarded as an unintended outcome of decades of free trade in the North American region. At first glance, this appreciation may seem hasty, but as I will show, it becomes compelling when situated within the broader context of thirty years of NAFTA. This mural—painted by a Mexican undocumented worker and depicting words and symbols of the Zapatista uprising that began in Mexico on January 1, 1994, the day NAFTA was enacted—remained for years on the wall of an otherwise ordinary hardware store (fig.1).

Located on the corner of Second Avenue and 117th Street, the mural has been recognized as a prominent cultural emblem of the Mexican diaspora in the East Harlem,[i] within El Barrio’s historically Puerto Rican enclave, which is now home to the largest Mexican community in the area. This observation is significant when considering the broader impact of long-term migration on a city like New York—a city built by immigrant labor and settlement. The mural’s endurance reveals how local communities actively utilize urban space to assert their right to the city: immigrants contribute to New York’s economic vitality while simultaneously demanding full political and cultural inclusion.

Figure 1. Zapatista Mural in the East Harlem, 2009. Photo by author.

The focus of this essay is the connection between the far-reaching consequences of NAFTA on the integration of a regional labor market shaped by Mexican migrant workers, the majority of whom are undocumented. It examines the mechanisms through which these migrants are (re)territorializing their class repertoires within their communities and spaces of arrival. Using the Mural Zapatista as an example, the essay explores how this process fosters new forms of political agency within the context of Zapatista transborder activism—practices that combine political awareness, grassroots organizing, and cultural production in the city. Through these engagements, migrants mobilize Zapatista notions of dignity, justice, sovereignty, and citizenship, adapting them to the realities of life in the urban landscapes of the United States.

“La esperanza es como las galletas de animalitos . . . no sirve de nada si no se lleva dentro.” Hope is like animal crackers; it won’t do you any good if you don’t carry it inside you. This phrase, originally cited in a communiqué by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), was added to the mural in both Spanish and English in 2009, the year of its restoration. I first encountered the phrase on the walls of La Garrucha, one of five autonomous spaces built by the Zapatistas in 1996 to host “The Intergalactic,” the First Intercontinental Encounter for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism, a gathering to which I shall return later in this essay.[ii]

The phrase lends significance to the mural’s iconography, linking the Zapatista rebel territories in southeastern Mexico with urban life in East Harlem. This symbolic connection is reinforced by other Zapatista slogans incorporated into the composition—“One world where many worlds fit,” “Chiapas,” “Democracy, Freedom and Justice!,”—as well as by prominent visual elements such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, Subcomandante Marcos (EZLN’s legendary spokesperson), and an Indigenous woman and her children depicted with ski masks, mirroring the Zapatistas themselves. At the mural’s base, the outline of a river visually integrates eastern and western regions of a borderland that does not exist in actual geographical coordinates, offering new meaning to the tangible social experience of El Barrio’s streets, buildings, and sidewalks, which form the mural’s backdrop.

The mural was designed and painted by Richar, a young Mexican painter, pre-hispanic dance performer, and activist. In 1993, Richar crossed the U.S.-Mexico border as an undocumented inmigrant, migrating from Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl, one of the more impoverished urban peripheries in the Mexico City metropolitan area. At the time, he did not realize that he was part of a larger wave of economic migrants who would ultimately supply the NAFTA labor market with undocumented Mexican workers.

News of the Zapatista uprising reached Richar just a few months after he had arrived in New York. When reflecting on the mural’s motivation, he described how Zapatismo resonated deeply with people like him, undocumented immigrants navigating precarity in the United States. For Richar, the Zapatistas provided not only a sense of hope but also a political vision for a better and more dignified life. Inspired by these ideals, he became politically active and later played an instrumental role in setting up Mictlán, a collective of undocumented Mexican workers in New York City.

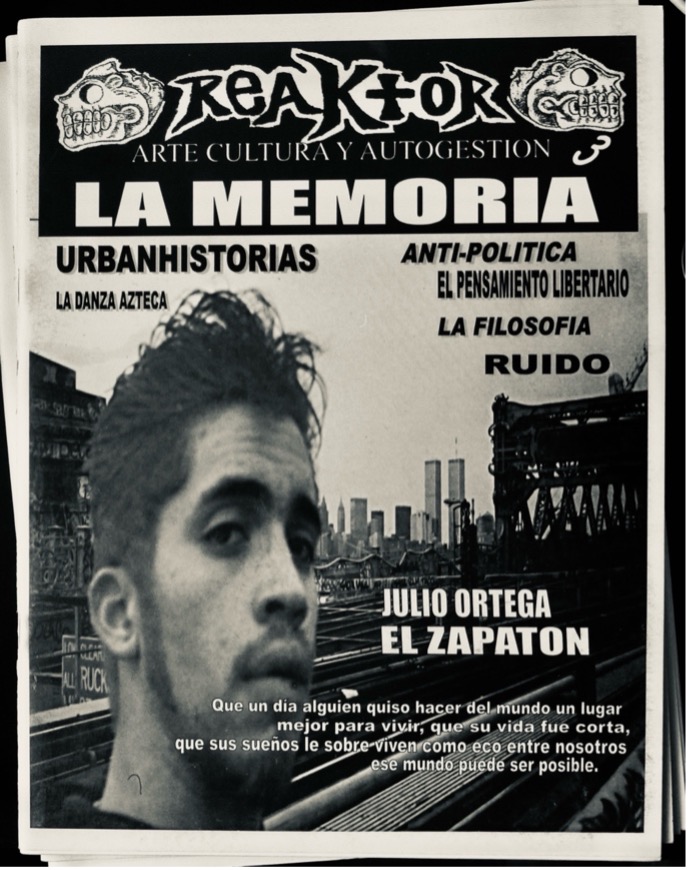

The Mictlán collective published REAKTOR, an independent zine funded through worker contributions and distributed freely throughout the city. REAKTOR functioned as a platform for advocating non-hierarchical political organization, solidarity, and independent education within the community of undocumented Mexican migrant worker (figs. 3 and 4). Education itself emerged as a central form of support for the Zapatista rebellion—or perhaps it was the rebellion that inspired new approaches to education—as reflected in the following editorial: “We respect independent thought because each head is a world, and REAKTOR is a world where many worlds fit.”[iii]

Figure 2. REAKTOR fanzine.

Figure 3. REAKTOR Fanzine.

Richar painted the mural in support of the Zapatista March for Dignity, [iv] explaining that he wanted to “show the world that there’s resistance everywhere,” as he stated in a video documentary chronicling the mural’s creation and later restoration.[v] His aim was to remain consistent with his vision as activist, seeking to involve others in the process so that the work would acquire a collective meaning. As the documentary shows, he succeeded. For this reason, the mural carries added significance as a record of the early experiences of Zapatista transborder activism in New York City. It became one of only two known murals in the United States to be recognized as significant evidence of the Zapatista rebellion’s impact on local communities and grassroots activism. [vi]

Intergalactic chronicles

As I have noted elsewhere, the 1996 Intergalactic encounter was a pivotal moment for Zapatismo. It marked a decisive step forward in the Zapatistas’ effort to position their own subalternity within the global political landscape of contemporary social movements. This strategic move enabled Zapatismo to shift from a locally grounded struggle to one with global resonance by fostering collaborative networks and alliances with international civil society organizations committed to resisting neoliberalism (Villegas 2008, 2024).

At the time, it was difficult to imagine that more than 6,000 participants from Mexico and over 43 countries would converge in southeastern Mexican to meet with an army of Indigenous rebels to collectively discuss strategies of resistance to global capitalism. In this sense, the Intergaláctico represents a pioneering instance of transborder activism, illuminating the intricate entanglements between the Global North and South in the context of NAFTA (fig. 5).

I also believe that this essay intended to situate the Zapatista Mural within the broader context of transborder activism—offers a compelling perspective on the flows of political imagination under NAFTA. It highlights the ways in which Zapatismo in the United States has been adopted and transformed by Mexican immigrants, becoming both a medium of resistance and a platform for advocating the rights of undocumented workers. Through cultural activism and political education, the mural materializes a shared political project that transcends national borders and links class experiences of the Global South with those of the North.

The spirit of the Intergalactic, popularized by the slogan “one world where many worlds fit,” has played a pivotal role in shaping these experiences of transborder activism. It serves as a symbol of collective, grassroots, and organized resistance, resonating across multiple global contexts: the World Trade Organization meeting protests in Seattle (1999), the first World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil (2000), the 2001 Quebec demonstrations against free trade (2001), the massive mobilizations in support of immigrant rights in the U.S in 2006, and the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2012. As demonstrated by the Zapatista Mural, this spirit turns the city itself into a platform for cultural activism—a space where visual narratives of resistance emerge and circulate against the forces of neoliberalism.

Within the broader context of thirty years of NAFTA, I hope that reconstructing these transborder chronicles also invites us to reconsider the effectiveness of the Zapatista Intergalactic spirit in annihilating space and time, forging connections between struggles from the South and those unfolding in marginalized spaces across the North American region. Here, William Burroughs’ observation that a photograph is not an image of the present but of the future becomes particularly resonant. Images—whether photographs or murals—transcend linear temporality. They materialize social histories, embody political imaginaries, and anticipate futures yet to come.

In this sense, the Zapatista mural, though not a photograph, functions as an image reflecting the present time and future of the social history and lived experience of Mexicans in New York City. Writing the full narrative that connects the Zapatista territories to New York City extends beyond the scope of this essay. My contribution is more modest: I propose that we “look” again at this and other transborder landscapes and continue to interrogate them for what they reveal about the power of collective imagination—the ongoing work of envisioning “one world where many worlds fit.”

Notes

[i] See: Mural-Mexican Diaspora. According to the website, the mural had been defaced with graffiti in 2015, and the property listed on the market in 2016.

[ii] In 2004, I visited this location and several Zapatista rebel territories as part of my dissertation fieldwork.

[iii] REAKTOR (ca. 2008).

[iv] This mobilization was one of the longest-lasting, demanding the approval of an Indigenous Bill on cultural and territorial rights (Villegas 2008).

[v] Zapata Vive la lucha sigue en NY! This work in-progress is about Zapatista solidarity and activism in the New York Mexican community. This is a collaborative project in which I am working with NYC-based Mexican video-maker Mictlán, and Mexican anthropologist Rodolfo Hernández. Trailer is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tgc_yeYgRQ4

[vi] The other is painted on the exterior of San Francisco’s independent City Lights Bookstore. It is a replica of a section of the community mural “Life and Dreams of the Perla River Valley,” painted by the late Sergio Checo Valdés in the Zapatista territories in Chiapas.

References

Historic Districts Council. Six-to-Celebrate Program: Mural—Mexican Diaspora. Accessed August 21, 2025.

Reaktor. ca. 2008. Reaktor [Independent zine, issue no. 5]. New York.

Villegas, Claudia. 2024. “From the Jungle to the World: Reterritorializing the Rural-Urban Divide Toward an Eco-Urban Revolution.” Berliner Gazette. Accessed August 21, 2025.

———. 2008. “Producing a Space for Dignity: Knitting Together Space and Resistance in the Zapatista Rebellion in Mexico.” PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Claudia Villegas is a Latin American Geographer whose research focuses on social movements, socio-spatial inequality in contemporary cities, and Mexican migration to the U.S. Claudia has been editor of ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities / Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades “Alfonso Vélez Pliego” at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, in Mexico.

Cite as: Villegas, Claudia. 2025. “Intergalactic Chronicles from Transborder Territories”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/intergalactic-chronicles-from-transborder-territories-by-claudia-villegas-delgado/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).