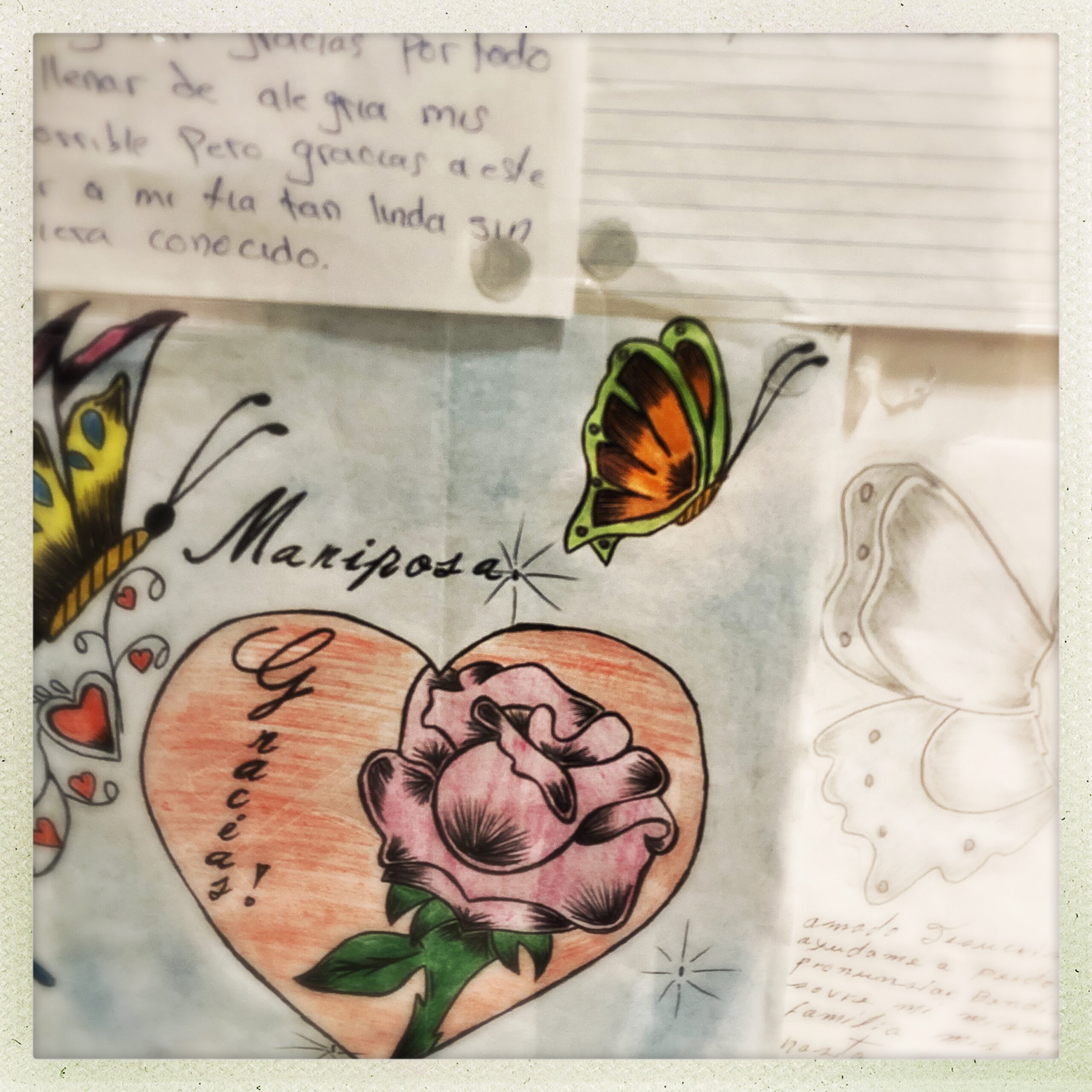

Close up of letters from people in US immigration detention, part of “En Medio: Senses of Migrations,” an exhibition at The Lilley Museum of Art, University of Nevada, Reno (2021- 2022). Photo by Deborah A. Boehm.

As we walked through the doors that led to an outdoor space, bright sunshine made it difficult to see. I was part of a group on what US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) calls a “stakeholder tour” at an immigration prison. Employees of the private prison corporation that owned and operated the detention facility explained that this was “the yard”—a place with no lawn, no trees, no green, no life. Rather, it was a large concrete box enclosed with metal fencing and layers of barbed wire. Throughout the space were small fenced-in areas that resembled dog runs. As one staff member explained, some individuals were further confined in these spaces when they came into the yard.

“Cages within cages,” said one of my colleagues.

Even this one small diversion from the brutality of indefinite detention—walking outside to spend a few minutes in a place that no one could reasonably escape from—entailed further imprisonment. Like so many moments over the course of my research about US immigration detention, seeing this indignity was heart wrenching. And, yet, as I have carried out fieldwork about this system of state violence, I have come to understand emotional experiences as central to the research itself.

* * *

While I was conducting previous research about how individuals and families navigated US deportations to Mexico, one interlocutor, Emy, told me about her experience of being detained by ICE. She described the horror of being treated like a “caged animal” (Boehm 2016, 52). Despite her infectious positivity and ability to find good in nearly every aspect of daily life, she broke down as she recalled the trauma of detention. She recounted how she had been filled with despair, had struggled to imagine a way out of that place, had contemplated suicide for the first time. That conversation with Emy led me to my current work about US immigration detention.

When I started the project, I knew it would be difficult to conduct fieldwork. Immigration prisons are out of sight, barely visible, difficult to access. State violence is intentionally out of view, unseen by design. So, I centered the invisibility, making it a primary theoretical focus, and asked questions that started with the concealed spaces of detention. Yet the difficulty of seeing immigration detention was not just because it was out of sight or difficult to access: it was, in every sense of the word, hard to see. It was also very hard, perhaps impossible, “to do justice” (Behar 1996, 9)—to carry out research about this system of suffering in a way that sufficiently, and justly, represented the experiences of people directly impacted by it.

* * *

“Your heart is broken,” my therapist said without pause. For me, trauma-informed therapy has been a rocky path out of a deeply painful place. Still, I’ve never really left. Once seen, the violence of detention cannot be unseen. I’ve tried to at least put it aside for moments: meditation, yoga, walks, fresh-cut flowers, gently placing the unspeakable in an imaginary box, on an imaginary top shelf to perhaps be revisited at a later time. But self-care can swiftly slip into what feels like self-indulgence. The body has a physical fight-or-flight reaction, my therapist explained, like when a wild animal is hunting you. True, a bear wasn’t actually chasing me—but I was witnessing a vicious attack, one that felt impossible to stop. Shocked, angry, outraged, overwhelmed, saddened, forgetful, distracted, detached. I was indeed heartbroken.

* * *

On that sunny, deceptively pretty day, as I stood in a state-sanctioned cage funded by taxpayer dollars, I remembered a previous conversation with Roberto, who had been detained at a different facility, in a different part of the country. He had told me how trips to the yard had saved him during the many years he had been imprisoned, before he was deported to a nation he had left as a teenager and hadn’t been back to for nearly four decades. There, the yard was also a concrete space, the rooftop of a notoriously dangerous and deadly county jail. Roberto recalled how he could see a church steeple—“well, at least the tip of it”—from certain parts of the yard. And, if the timing was right, he could hear church bells, or watch the sun setting. “It gave me hope,” he explained. Then, guards would take him back to a cell in the building’s basement, an underground labyrinth filled with more cages.

A volunteer who visited people at that jail had started to send books about birdwatching to friends inside. She acknowledged that while it might seem odd to do so, a man had told her that the books were surprisingly comforting—rather than reminding him of what he could not do, reading about birdwatching was a temporary escape from that carceral cave. For just a moment, the cage door was open and he could see a way out.

* * *

Fieldwork can be hard. Research is a challenge to set up, difficult to start, hard to continue, hard to wrap up. Fieldwork can be interrupted, blocked, or impossible. It’s hard to create an end product that will be recognized within the academy, or that will reach a public audience, or that will justly describe the experiences of collaborators. It is hard to write about violence and human cruelty—at times, unspeakable—but hard not to write about it as well. It can be hard to see what we see, to reflect on what we’ve observed, to analyze materials we’ve gathered. The stories people share can be hard to tell. Fieldwork can be heartbreaking.

When we are taught, and teach, the basics of ethnographic fieldwork, we often turn to an emic approach as the appropriate way to study family life, or analyze rituals, or consider forms of reciprocity. But when research focuses on the most brutal of human acts, do the experiences we observe also need to be felt? Just as we reflect on how our positionality shapes fieldwork, what might come from a form of reflexivity that centers the emotional?

* * *

In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, in yet another caged yard, people detained in California’s Central Valley came together and stood side-by-side to form a heart. An aerial photograph shared by activists captured this act of solidarity, collective action protesting the US government’s disregard for human life. People in detention called on ICE to release them, to not permit detention to become a “death sentence” because of COVID. As prison guards stood on the periphery, people affirmed our shared humanity. This heart formed by humans was seen, and felt. Even from behind the yard’s concrete walls, it was visible, clear, definitive. Seeing and observing are foundational to the anthropological endeavor—perhaps feeling should be as well.

On that day, as people stood together in the shape of a heart, they expressed care, community, love. They embodied freedom. They revealed the possibility for something different, a future in the making. It can be hard to see an end to carceral systems, but as we turn our view toward the unseen, even if it breaks our heart, we can collectively find—and follow—a path out of the shadows.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by support from the American Council of Learned Societies, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Freedom for Immigrants, and University of Nevada, Reno. The statements made and views expressed are solely my responsibility. Special thanks to Sara for showing me what is possible. Above all, I am grateful to the many people impacted by immigration detention who have so generously shared their stories.

References

Behar, Ruth. 1996. The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart. Beacon Press.

Boehm, Deborah A. 2016. Returned: Going and Coming in an Age of Deportation. California Series in Public Anthropology 39. University of California Press.

Deborah A. Boehm is Foundation Professor of Anthropology and Gender, Race, and Identity at the University of Nevada, Reno. She is author of Intimate Migrations: Gender, Family, and Illegality among Transnational Mexicans and Returned: Going and Coming in an Age of Deportation. Her current research focuses on the unseen spaces of U.S. immigration detention regimes and community coalitions working to end carceral systems.

Cite as: Boehm, Deborah A. 2025. “Hard to See.” In “Anthropology that Breaks Your Heart: Loss and Found,” edited by Salwa Tareen, Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori, and Hosanna Fukuzawa, American Ethnologist website, 24 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/hard-to-see-by-deborah-a-boehm/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).