NAFTA’s thirtieth anniversary year was marked by a major trade dispute. Mexico defended its position to limit the production and use of genetically modified (GM) corn and glyphosate within its borders, citing concerns about their effects on maize biodiversity and human health. At the center of maize biodiversity and domestication—with fifty-nine distinct landraces and thousands of local varieties—Mexico occupies a unique position globally. In 2020, then-President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) issued a decree banning GM corn for human consumption and prohibiting the use of glyphosate.[1] The presidential decree drew on two decades of activism by the anti-GM corn movement, which emerged after transgenic corn was discovered among traditional fields in Oaxaca’s highlands in 2001. This moment marked a turn away from the neoliberal agricultural policies of previous governments. However, in late 2024, a trade dispute panel ultimately ruled in favor of the United States (and with Canada, as a third party) and against Mexico’s plans to restrict GM corn, determining that the ban violated the terms of NAFTA 2.0, or the United States—Mexico—Canada Agreement (USMCA).

The Neoliberal Corn Regime

NAFTA has been central to a series of corn-related policies that have profoundly affected the Mexican countryside. Together, these policies have exacerbated the challenges faced by campesinos, raised concerns about GM corn and biodiversity, contributed to rural out-migration and circular migration, and altered corn-based diets for both rural and urban consumers. A bitter consequence of a global food system dominated by liberalized trade and corporate concentration is that countries like Mexico now import basic grains they have historically produced. In Mexico’s case, maize (or corn) is a crop of deep cultural and economic significance. Cuts to rural support programs, mandated as part of NAFTA’s implementation, were followed by a surge in ‘dumped’ US corn imports. This influx, in turn, increased the export of labor, both to maquiladora factories and to the United States (and, to a lesser extent, Canada) as migrant agricultural and service-sector workers. Between 1995 and 2005, roughly half a million agricultural workers were displaced from the Mexican countryside (Pérez et al. 2008). Indeed, in the early days of the Mexican anti-GM corn movement, when I began conducting interviews and participant observation with its organizers, many linked the government’s prioritization of cheap corn imports over rural supports to its broader aim of transforming campesinos into a low wage work force.

A de facto moratorium on the cultivation and field testing of GM corn was imposed in late 1998 by the National Agricultural Biosafety Committee (later CIBIOGEM) because of concerns that GM corn could hybridize with and displace traditional varieties and teosinte, a wild relative of maize. Moreover, the traits most commonly tested in field trials were of little benefit to Mexican agriculture. In 2001, scientists detected transgenic DNA sequences in traditional maize varieties in the highlands of Oaxaca. GM corn had likely entered the country through U.S. imports, where roughly 25 percent of cultivated corn was transgenic at the time.

White corn is preferred for making tortillas and other traditional foods (and, to a lesser extent, blue corn and other colored varieties). Imports from the United States—mostly yellow GM varieties—are generally used as animal feed or in industrially processed foods, including some brands of totopos (corn chips) and tortillas. In 2002, scientists and activists found evidence of transgenes in the government’s own corn supply and in maize fields elsewhere in the country, including in the Tehuacán Valley, where I conducted fieldwork with corn-producing campesinos between 2001 and 2008 (see Fitting 2011; Ezcurra, Ortiz, and Soberón 2002; INE-CONABIO 2002). Today, over 90% of corn grown in the United States are GM varieties.

The Recourse to Corn

In times of crisis, when social services collapse or cannot effectively carry out their functions, corn’s importance becomes self-evident. Recourse to corn is the last line of defense for security, for hope, for the retreat of lesser units of society in order to defend their very existence.

— Arturo Warman 2003 [1988], 20

As the cornerstone of rural livelihoods and a central ingredient of culinary traditions and diet, maize is Mexico’s most significant crop. It is cultivated on roughly 60 percent of the nation’s farmland, under a vast array of conditions—from rainfed, small-scale, and low technology agriculture geared toward subsistence, to irrigated, large-scale industrial production. Like in many other regions, campesinos from the southern Tehuacán Valley grow traditional and creolized varieties of maize.[2] Yet most households depend on multiple sources of income, including maquiladora work and labor migration, particularly among younger residents. Farming alone is rarely sufficient, and for younger residents at the time of my research, it was not an appealing livelihood, though this perception may shift with age.

Following the implementation of NAFTA, valley residents found that farming traditional and creolized varieties of maize cost at least as much as purchasing imported corn. Although residents preferred the taste and texture of local or regional maize for making tortillas, imported or industrial grain was markedly cheaper at the local market.

One maize farmer in his late sixties explained that people continued to cultivate corn even though it was not profitable because “there is no work here except in the fields. If you are older, they’re not going to give you a job.” Since older residents are less likely to find employment, corn farming remains one of the few ways they can contribute food or income to the household. This is connected to what anthropologist Arturo Warman (1988) describes as the “recourse to corn,” the campesino’s last line of defence. Corn is also a particularly flexible crop with multiple uses: it can be dried, stored, and transformed into masa (dough for tortillas and tamales) or sold as fresh corn or grain. [3] A younger farmer similarly remarked, “Some of us grow corn because there is no other work. Not everyone can get a job or make it across the border.”

Figure 1. Photos of poster and cornfields in the Tehuacán Valley. Photos taken by author.

Resisting GM Corn

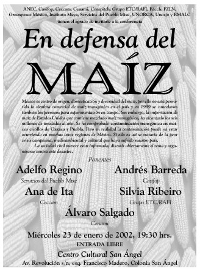

In response to NAFTA, shifting rural policies, and the controversial discovery of GM corn growing in traditional cornfields, resistance to GM corn intensified. The En Defensa del Maíz (or In Defense of Maize) campaign organized its first forum in Mexico City in 2002, and a few years later the Sin Maíz No Hay País (Without Corn, there is No Country) campaign emerged. At the first forum held in early 2002, the meeting hall was crowded with attendees and speakers, including a representative from the National Support Center for Indigenous Missions (CENAMI) who explained how the government of the time viewed small-scale corn producers: “[T]he government perspective is: We don’t need campesinos, nor do we need Indigenous communities. We need people who can work in the maquiladoras [factories]” (January 24, 2002). These campaigns brought together—and strengthened existing networks among—environmental, campesino, and Indigenous rights organizations, as well as academics, researchers, and scientists. Although rooted in Mexico, the movement also developed transnational connections and support. Two organizations with offices in Mexico City—Greenpeace Mexico, and the Action Group on the Environment, Technology, and Concentration (ETC Group)—were among its most vocal participants, serving as founding members of En Defensa del Maíz. Both had raised concerns about GM corn imports in the years leading up to the controversy. As the movement grew, it attracted attention and support from NGOS and activist networks internationally.

By linking GM corn imports, regulation, and cultivation to neoliberal policies that undermined small-scale farmers’ livelihoods—policies such as trade liberalization, cuts to rural subsidies, and the commercialization of seed—En Defensa del Maíz forged and extended connections across regions and national borders.

As a powerful and longstanding symbol of the Mexican nation, maize invokes elements of shared culture across multiple scales of place, ranging from small rural communities and regions to the nation as a whole, and even beyond Mexico’s borders to Indigenous and rural parts of the Americas. For example, while Indigenous campesinos of the highlands of Oaxaca or the Tehuacán Valley refer to themselves as the “people of maize,” so too might campesinos, seed activists, and Indigenous groups elsewhere, such as the Zenú in Colombia. In countries where there are place-based cultural attachments to maize—like Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, and among some Indigenous nations in the United States—the primary focus of anti-GM activism was, and continues to be, corn (Grandia 2024; Fitting 2019).

At the various workshops and forums I attended in Mexico City over the years, participants often framed GM corn as a symbol of contemporary imperialism and as an erosion of sovereignty. Because GM corn is patented and must be purchased each season, and because it was discovered growing in Mexico despite the moratorium on cultivation and testing, it has been understood as undermining the ability of resource-poor campesinos, their communities, and even the national government to set their own agendas regarding seeds, biodiversity, and agriculture. The late 2024 USMCA trade dispute decision represents another instance of these challenges to Mexico’s sovereignty.

In contrast, at anti-GM forums, traditional and creolized varieties were, and continue to be, defended not only as vital to maize biodiversity and food self-sufficiency, but also as central to the principle of food sovereignty, or “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” In the 2007 forum for the Defense of Maize and Food Sovereignty, participants defined food sovereignty in way that highlighted autonomy and self-determination.[4] That same year, the Sin Maíz No Hay País campaign was launched to advocate for the protection of traditional maize varieties, but also in response to rising tortilla prices. High tortilla prices became a talking point in the presidential election of the time, and in early 2007, protest marches were organized that drew some 75,000 participants to Mexico City’s zócalo.

Figure 2. Sin Maíz No Hay País website. Screenshot taken by author on October 28, 2024.

Despite the efforts of activists, the moratorium on field trials of transgenic corn ended in 2009, and Mexico allowed experimental plots of GM corn to be planted. Monsanto, Dow Chemical, and DuPont’s Pioneer applied to enlarge their small experimental plots, with the goal of establishing the first commercial fields in northern Mexico. Activists intensified their efforts to garner support for a government rejection of these corporate applications. In January 2013, the National Union of Autonomous Peasant Organizations (Unión Nacional de Organizaciones Regionales Campesinas Autónomas, or UNORCA) held a sit-in and hunger strike at Mexico City’s Ángel de la Independencia monument; thousands joined anti-GM protests that month and again in May. In the autumn of 2013, following a class action lawsuit filed by a coalition of community organizations, a federal district court judge issued a precautionary injunction on any new permits for experimental and trial planting of GM corn (Wise 2019, 175). Farmers’ organizations from Oaxaca declared 2013 “the year of resistance to transgenic maize.” Years later, when Mexico’s Supreme Court rejected appeals from Bayer/Monsanto, Syngenta, Corteva-DuPont and Dow in 2021, it upheld restrictions on the cultivation of GM corn. However, imports of yellow GM corn from the United States continued.

In 2023, when then-President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) issued an executive order to restrict the use of glyphosate, ban the cultivation of GM corn, and phase out its use in animal feed and processed foods, the measure was, unsurprisingly, countered by both biotech corporations and the U.S. government. Bayer (which by then had acquired Monsanto) challenged the decision before Mexico’s consumer protection regulator. Under the conditions of NAFTA 2.0 (USMCA), the U.S. government initiated a dispute over Mexico’s restrictions. In response, Mexico argued that its measures did not violate the terms of the trade agreement, as they neither restricted imports nor significantly affected U.S. corn exporters, but rather prohibited the use of GM corn in food for direct human consumption, such as tortillas. Under the dispute resolution process, civil society organizations from all three signatory countries were invited to submit statements in defense of Mexico’s right to restrict GM corn.[5]

Prominent critics of GM corn were part of AMLO’s government. Víctor Suárez, who had been a leader in the Sin Maíz, No Hay País campaign, was appointed Undersecretary for the newly established Food Self-Sufficiency branch of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. To increase domestic maize production—particularly of non-GM white corn—and reduce imports of US corn (GM yellow corn), the Ministry took steps to return to pre-neoliberal price supports and subsidies for smaller-scale farmers. They also promoted alternatives to replace corn in animal feed. Describing the series of policy changes to support increases in the production of corn domestically, Suárez explained: “Our strategy is aimed at structurally differentiating non-GM white speciality corn for human consumption from commodity corn prices.”[6] Such pricing policies and government commitments to buying domestic corn, however, have had mixed results and reactions.

A notable shift in more recent years of anti-GM corn resistance—foregrounded in Mexico’s rebuttal during the trade dispute—has been an emphasis on the potential health effects of glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide in Mexico and worldwide. While Canada and the United States maintain that glyphosate residues in foods do not pose a health risk, Mexico’s rebuttal argues that these assessments overlook national dietary differences. Mexicans consume far greater quantities of corn, and therefore potentially higher levels of glyphosate residues, than have been scientifically studied. In Mexico, corn is eaten in minimally-processed forms at roughly ten times the rate of consumption in Canada and the U.S.

An additional challenge identified by seed activists and others concerns Mexico’s obligation, under NAFTA 2.0 and the Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), to accede to the 1991 version of the International Union of the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). The earlier 1978 version of UPOV included both a “farmer’s privilege” clause, allowing farmers to save and replant seeds, and a “breeder’s exemption,” which permitted breeders to freely use protected varieties in research and planting. The 1991 revision, however, eliminated these clauses, extending patent-like protections to plant materials and seeds. These changes have raised concern among seed scientists and activists alike.[7] With the renegotiation of NAFTA in 2017 and with the ratification of CPTPP in 2018, Mexico is now required to adhere to UPOV 91, although it has not done so.

In the wake of losing the 2025 trade dispute with the United States, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum successfully advanced a constitutional amendment prohibiting the cultivation of GM corn within Mexico. The amendment was approved by the Mexican Senate in early 2025. While both the current administration and that of AMLO have markedly distanced themselves from neoliberal policy frameworks in an effort to enhance Mexico’s food self-sufficiency and advance food sovereignty, the outcome of these efforts has thus far been uneven. USMCA is scheduled for review by the three signatory countries in 2026 and will likely entail renegotiation. At this point it is unclear what changes will be made to the agreement.

Notes

[1] President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s decree included: an immediate ban on the use of GM corn for human consumption (white corn), the revocation of any existing GM corn authorizations and no further approvals, a phase out of the use of GM corn in animal feed and processed foods, and a phase out of the use of the herbicide glyphosate. The decree states that “The main purpose of these measures is to protect the right to health and a healthy environment, native corn, the milpa, biocultural wealth, peasant communities and gastronomic heritage, as well as to ensure a nutritious, sufficient and quality diet.”

[2]“Traditional,” “native,” or “local” varieties refer to landraces maintained and improved by farmers in the field. These stand in contrast to “modern” or “improved” varieties developed through scientific plant breeding or biotechnology. The word criollos is commonly used in rural Mexico to refer to both traditional and creolized varieties, the latter of which are the outcome of intentional or unintentional mixing between landraces and scientifically improved varieties. The terms maize and corn can have different connotations but I use them interchangeably here for the sake of ease. For further discussion, see Fitting 2011 or Wise 2019.

[3] For centuries maize has provided not just a key food staple, but it was used for making alcohol and as animal feed, in addition to a plethora of other uses for the various parts of the plant, such as leaves for tamal wrappers or in decorations and cobs for fuel. During the twentieth century, these uses multiplied as corn became an ingredient in processed foods, ethanol, sweeteners, and bioplastics. In the twenty-first century, there has been a global trend toward multipurpose agriculture or “flex crops” and corn has played a central role in this shift (see Fitting 2024).

[4] From the Declaration of the Forum for the Defense of Maize and Food Sovereignty September 13, 2007:

“For us, food sovereignty:

- signifies the right of “los pueblos” (peoples) to self-determination

- is part of the defense of culture of our peoples (los pueblos), the defense of land and territory

- is a fundamental element in guaranteeing political sovereignty: a people that cannot produce its own food is highly vulnerable to dependency and subjugation. For this reason, food sovereignty is not only a concern for peasants and indigenous peoples, but for all Mexicans.

- is the right of communities, peoples, and nations to determine their own policies on agriculture, food, land, the economy, and the environment necessary to guarantee dietary staples for its population, without such policies being imposed upon them by corporations and powerful countries.

- is the required legislation and policy for agri-food production to be supplied by national producers so that they produce enough food, with priority given to peasants and small producers based on forms of environmentally sustainable production. This implies the right of peasants to land, water, seed, and natural resources.

- is to enforce the human right to food, which implies access to healthy food in the amount and quality appropriate to cultural preferences” (Author’s translation, GEA 2007, 120).

[5] However, Canadian organizations –the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network and Council of Canadians (CBAN)—were notified that their invitation to contribute had been rescinded at the request of the U.S. and Canadian governments because Canada was a third party rather than a disputing party in the process.

[6] For instance, in Sinaloa, the government at the state and federal levels implemented a new supply management system which removed non-GM white corn from the formula for corn commodity prices. Instead, it treats non-GM white corn as a speciality crop, distinct from the yellow corn, traded on the Chicago grain exchange. The two levels of government committed to purchasing corn at a guaranteed price, set above the Chicago price, from farmers, including medium-scale and smaller-scale campesinos who have 15 hectares or less.

[7] With NAFTA, Mexico had signed UPOV 78 and passed a corresponding Federal Law of Plant Varieties (LFVV). See Tadeo Robledo and Espinosa Calderón’s 2019 news story (“Patentar semillas, el atentado que se prepara contra el campo mexicano,” in La Jornada del campo) and La Via Campesina Mexico’s website for criticism of UPOV.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to valley residents who hosted and welcomed me over the years. I would also like to thank Antonio Serratos, Alejandro Espinosa Calderón, and Regino Melchor Jiménez Escamilla for their insights, along with many other interviewees and interlocutors. My thanks also go out to Alejandra González Jiménez and the editors for their suggestions. All errors are, of course, my own.

References

Ezcurra, Exequiel, Silvia Ortiz, and Jorge Soberón. 2002. “Evidence of Gene Flow from Transgenic Maize to Local Varieties in Mexico.” In LMOs and the Environment: Proceedings of an International Conference, 277–83. OECD, Raleigh-Durham, United States, November 27–30.

Fitting, Elizabeth. 2011. The Struggle for Maize: Campesinos, Workers, and Transgenic Corn in the Mexican Countryside. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2019. “GM Crops and the Remaking of Latin America’s Food Landscape.” In Placing Latin America: Contemporary Themes in Human Geography, edited by Fernando Bosco and Edward Jackiewicz, 143–56. 4th ed. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

———. 2024. “Corn.” In Handbook of Agricultural History, edited by Jeannie Whayne, 251–68. New York: Oxford University Press.

GEA (Grupo de Estudios Ambientales). 2007. La Contaminación Transgénica del Maíz en México: Luchas Civiles en Defensa del Maíz y de la Soberanía Alimentaria. Estudio de Caso. Mexico City: Grupo de Estudios Ambientales, A.C.

Grandia, Liza. 2024. Kernels of Resistance: Maize, Food Sovereignty and Collective Power. University of Washington Press.

INE-CONABIO (Instituto Nacional de Ecología – Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). 2002. Evidencias de Flujo Genético desde Fuentes de Maíz Transgénico Hacia Variedades Criollas. Presented by E. Huerta at the En Defensa del Maíz conference, Mexico City, January 23.

Pérez, Mamerto Sergio Schlesinger, and Timothy Wise. 2008. The Promise and Perils of Agricultural Trade Liberalization: Lessons from Latin America. Washington, DC: Washington Office on Latin America.

Pérez Ruiz, Rigoberto V., Jose E. Aguilar Toalá, Rosy G. Cruz Monterrosa, Adolfo Armando Rayas Amor, Martha Hernández Rodríguez, Yolanda Camacho Villasana, Jerónimo Herrera Pérez. 2024. “Mexican Native Maize: Origin, races and impact on food and gastronomy.” International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 37: 100978.

Warman, Arturo. 2003 [1988]. Corn & Capitalism: How a Botanical Bastard Grew to Global Dominance. Translated by Nancy L. Westrate. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Wise, Timothy. 2019. Eating Tomorrow: Agribusiness, Family Farmers, and the Battle for the Future of Food. New Press.

Elizabeth Fitting is an anthropologist whose research has explored various aspects of food and migration, including debates around transgenic maize in Mexico, and more recently, the experiences of migrant farmworkers employed through Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program.

Cite as: Fitting, Elizabeth. 2025. “GM corn and challenges to Mexico’s food sovereignty”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/gm-corn-and-challenges-to-mexicos-food-sovereignty-by-elizabeth-fitting/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).