Stefania Pandolfo’s Impasse of the Angels: Scenes from Moroccan Space of Memory (1997) and Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star (1977) are strikingly similar texts coming from different disciplines. The former is an ethnography; the latter, fiction. They both touch on loss, trauma, and death. And more intriguingly, they share some formal qualities that are usually found in fiction. Both texts, for example, are fragmented and polyphonic to an extreme—to the point where categories of author and character get destabilized, making the reading experience disorienting. They both resist interpretive mastery, which, since they are concerned with the ethics of representation, translates to a preservation of the irreducibility and unknowability of the other. This “other” takes the form of the Maghribi peoples living in the fractured postcolonial present of the Draa valley in Pandolfo’s ethnography. In Lispector’s novel, the “other” takes the form of an abjectly poor woman named Macabéa, whose life, though fictional, is inspired by the numerous women living in poverty in Northeastern Brazil.

I argue that the similarities in unconventional narrative strategies across these two texts highlight how porous the boundary between literature and anthropology can be. Further, these narrative strategies are ethical stances on the part of the authors, making their characters elusive and thus preventing readers from forming too-quick judgments.

Fractured form and polyphony in Impasse of the Angels

In contrast to the more “realist” modes of ethnographies that usually have a unifying authorial voice, Pandolfo offers a form that might be called “ethnographic surrealism,” which is undergirded by a modernist disposition toward reality that views reality as fragmented, contested, and unstable. In terms of formal qualities, inventive juxtaposition or collage (surrealism’s favored technique) characterizes this mode of ethnography (Clifford 1981, 552). In chapters “Loss 1” and “Loss 2,” for instance, Pandolfo juxtaposes her dream about stairs, sweeping (shetteb), and unmarked graves with the Maghrebi rite of forgetting, their metaphor of “forgotten graves,” a passage from the Kitāb al-Raḥmah fī al-ṭibb wa-al-ḥikmah (The Book of Mercy in Medicine and Wisdom), a description of a cemetery (Mdina of Lalla ud Sidi), dream theories from Lacan, Freud, and Ibn al-Arabi, conversations with Maghrebi speakers, and so on.

Certainly, the fragmented form of the text mimics the “fractures, wounds, and contradictions” of the Maghribis and Morocco and is thus a consequence of the particular locale, its history, and its cosmology. That is, it follows the ongoingness of the struggles and contradictory ways of sense-making that they practice. But the form also enables a preservation of the unknowability of the other—in this case, the Maghribis. The juxtaposition and proliferation of images, metaphors, etc., gestures toward an incompleteness and an excess. That is, we only get a glimpse into these lives, and the materials Pandolfo analyzes are not exhaustive. We cannot cross over to a complete understanding of these lives because they are in excess of our ability to apprehend them.

Additionally, since the elements in her juxtaposition are paratactic—i.e., not hierarchically arranged—all ethnographic material, no matter how disparate, with all their contradictions, say something significant about the Maghribis. This is why one cannot invalidate dreams as a form of knowledge in the Draa valley. The lack of a hierarchical knowledge system means that readers cannot build toward some sort of cumulative knowledge; the materials are only thematically resonant. Pandolfo makes this clear in her introduction: “this text […] is not a referential entity […]. Nor is it an objective map of verbal statements […] that may as such become objects of knowledge” (1997, 3).

By abruptly shifting from one voice to another, sometimes with minimal indication and sometimes leaving quotations unattributed, Pandolfo also effects an entanglement of voices. I understand this as is another ethical move on her part, because she is partially renouncing her ownership over the text. When she writes about her dreams, for example, she says, “In dreaming, I am visited by others, and the knowledge I find in myself upon awakening is never only my own” (1997, 189). And later, “the dream […] is both mine and not mine” (1997, 199).

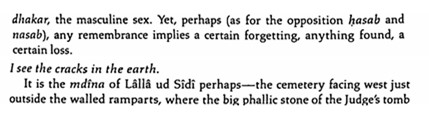

And this bears out in the text, as fragments from Pandolfo’s or perhaps someone else’s dream interrupt the sequence of the passages, forming the joint in the juxtapositions, as we see in this brief excerpt:

A section of Pandolfo’s book, pages 168-169. “I see cracks in the earth” has no attribution and interrupts the two passages. Photo by Yash Chitrakar.

This type of fragmented writing, especially when about both catastrophic and traumatic loss (under colonialism or otherwise), keeps the loss in view without letting it wholly define the subsequent actions and lives of the people who have faced the loss. It allows for an opening of possibilities because these fragments may be rearranged. This is exactly what the Maghribis presented in the text do with their own fragments of memories, poems, and stories—what Pandolfo sees as “forgetting.” This “forgetting” manifests as narrative violence or rupture that arises from an inability to narrate trauma since it “infiltrates the whole body and brings about dissolution and death” (1997, 208) while at the same time intimating livability amongst fragments.

Dissolving voices: The deliberate obfuscation of character in The Hour of the Star

Lispector makes a similar move in The Hour of the Star. The pain and loss that this text tries to reckon with is Macabéa’s, as she lives in abject poverty and then dies an enigmatic death. Although she does not seem to recognize her own pain, Rodrigo, the narrator of the story, does. He writes because he feels Macabéa’s pain, and for him, the pain manifests as a toothache: “The toothache that runs through this story has given me a sharp stab in the middle of our mouth” (1977, 3, my emphasis). Because he feels this pain, Rodrigo describes this act of writing as “screaming,” and not speaking, which would be far too articulate. Rodrigo constantly worries about the inadequacy of language to describe any reality completely, least of all the reality of another person’s pain.

This screaming as inarticulateness becomes an ethical act in the story, as it shrouds Macabéa under a veil of words that lends no sure knowledge about her to the reader. The more Rodrigo produces Macabéa for the reader’s eyes, the more she becomes unknowable. As he says, “the story is true though invented” (1977, 3); this irresolvable tension between invention and truth animates the entire text. The unreliability and excessive self-consciousness of Rodrigo make the reader suspicious of his claims about Macabéa. As to the kind of truth professed here, Rodrigo says that truth is “inexplicable contact” (1977, 3). While the text points to a possibility of true contact between Rodrigo and Macabéa, it also gestures to the impossibility of communicating that contact in an understandable way. Preserving Macabéa’s otherness, then, is arguably the text’s overarching motivation.

I want to dwell further on the sentence, “this story has given me a sharp stab in the middle of our mouth.” The transition from “me” to “our” here is an example of Lispector’s dissolving of the categories of author (Lispector), narrator (Rodrigo), and character (Macabéa). In the dedication to the book, Lispector writes, “…in that instant I exploded into: I. This I is all of you [readers] since I can’t stand being just me” (xiv). The heading itself, which says, “Dedication by the Author (actually Clarice Lispector),” adds to the effect. The literal separation of “author” and “Clarice Lispector” displaces Lispector from authorhood. Further, the word “actually” opens up a suspicion in the reader about whether Lispector is even the author. This works to further add to Macabéa’s opacity.

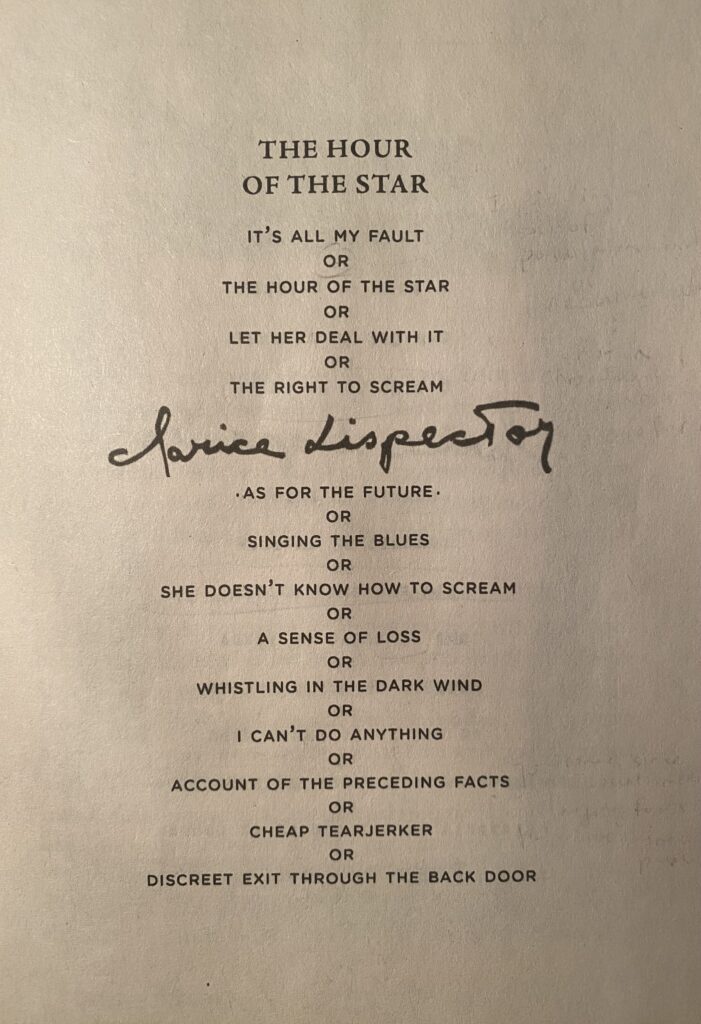

This opacity extends beyond death. In fact, the form of the text rescues Macabéa from being frozen or defined by death. It does so by the use of parataxis, a literary device that juxtaposes elements of a text without ordering them hierarchically. In the contents page of The Hour of the Star, the “chapter titles” are not just out of order but are separated by the conjunction “OR.” There is no sequential or hierarchical order to follow. The book is entirely anti-evental because it seems as if there is not even a story one can build here, if one understands stories to be accumulative sequences of events. It’s not a matter of “this happened and then that happened” but, rather, “this happened or that happened,” where neither “this” nor “that” is more significant than the other. We cannot chronologically construct Macabéa’s life narrative. In her death, she is called a star, and her final words are, “as for the future” (75). This closing has a hint of irony—because Macabéa is dead— and because the future-facing gesture negates both the finality of death and the idea of linear chronology.

Contents page of The Hour of the Star. Photo by Yash Chitrakar.

One might ask, why go through the trouble to protect otherness in fiction? Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that, although Macabéa is not real, her character is hooked to the actual social world of Northeastern Brazil. Lispector writes from an experience of poverty. Cinthya Torres, a scholar of 20th and 21st century Amazonian literature, writes that, “Poverty was a tangible experience for Lispector, first during the family’s early years in Maceió and later during her childhood in Recif” (2017, 195). And although Lispector moved on to live a more middle-class life, like Rodrigo, she felt a social commitment to write about poverty, while at the same time recognizing that there are “contradictions and restraints of language in the depiction of the Other.” For her, an act of imagination was not enough to depict poverty and hunger (2017, 194-195). And so, she resorts to using rhetorical and narrative strategies to challenge “the reader to reevaluate his [sic] views and preconceptions on poverty, justice, and empathy, while simultaneously reflecting on the creative process of writing” (2017, 197). The Hour of the Star, then, reveals its artificiality, insists on Macabéa’s presence, and borrows from the real with a sense of ethical responsibility toward the actual social source.

Contesting the boundaries between literature and anthropology

So, what does this mean for the boundaries between literature and anthropology? To be sure, the “other” in Lispector’s novel is fictitious, but she is working with her experience of the world—and as such, is borrowing from the lives of actual others. Pandolfo is representing Moroccan people by giving credence to both the usual forms of ethnographic evidence and some forms that may be considered either atypical or even inadmissible; at best, perhaps, epistemologically problematic. For Pandolfo, storytelling, dreams, poetry, symbolic maps, etc., all are worthy of attention. On a general level, there is some amount of invention happening anyway when one writes anthropology, stitching together real events and lives to form a narrative. Moreover, there is consensus amongst anthropologists that the disciplinary boundary between anthropology and literature is not stable and has always been contested (Fassin 2014; Brandel 2020; de Angelis 2003); after all, there are ethnographic novels and novelistic ethnographies.

For anthropologist Didier Fassin, both literature and anthropology treat the “raw material” of life, but they do so in different ways. For Fassin, the difference has to do with the type of authority and register of “reality” that these two disciplines deploy. He writes, “while fiction could never claim to simply reproduce the real, the argument that it is faithful to reality gives ethnography a form of authority that has important ethical and political consequences” (2014, 53). He respects the latter’s “fidelity to facts” (Fassin 2014, 51). This “authority” and “fidelity” allow ethnographies to explain the particular lives they encounter by reference to larger socio-political structures (Fassin 2014, 46). However, it is exactly this kind of authority that Pandolfo wants to eschew; explaining the situation of the Maghrib wholly through larger structures would be to flatten the contradictions and contestations of identity present in the fractured and wounded Morocco. In Lispector’s case, any kind of generalization that Rodrigo makes about Macabéa has to be taken with more than a grain of salt.

Both texts reject an authoritative stance and enact an ethics of uncertainty, openness, and entanglement. And both texts gesture toward the presence of the Other without presuming an understanding. This is what is afforded to both texts by their formal choices, and it is worth paying attention to the formal features of these writing genres as ethical and representational tools.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dr. Naveeda Khan and my peers from the School of Theory and Criticism (SCT) held in Ithaca in the summer of 2025. Everyone’s passionate intellectual engagement not just with the course material but also with everything they encountered was inspiring. Those six weeks will live on long in my memory.

References

Brandel, Andrew. 2020. “Literature and Anthropology.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology.

Clifford, James. 1981. “On Ethnographic Surrealism. Comparative Studies in Society and History.” 23(4): 539-564. .

De Angelis, Rose. 2003. “Introduction.” In Between Anthropology and Literature, edited by De Angelis, Rose. Routledge.

Fassin, Didier. 2014. “True life, real lives: Revisiting the boundaries between ethnography and fiction.” American Ethnologist, 41(1): 40-55. .

Lispector, Clarice. 1977. The Hour of the Star. Penguin Group.

Pandolfo, Stefania. 1997. Impasse of the Angels: Scenes from Moroccan Space of Memory. University of Chicago Press.

Torres, Cinthya. 2017. “On Poverty and the Representation of the Other in The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector.” INTI, 85(14): 193–203.

Yash Chitrakar is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Rochester. He is interested in affect theory, narrative ethics, and aesthetics. He is currently writing a prospectus, exploring how modernist writers deploy wonder—thematically and formally—and concepts about childhood in service of recovering from the losses faced during the first half of the 20th century. He is looking into writers like Willa Cather, D.H. Lawrence, Samuel Beckett, and Elizabeth Bishop for their treatments of movement and exile and the role wonder and childhood play in their senses of possession and dispossession.

Cite as: Chitrakar, Yash. 2026. “Exploring Narratological Tools at the Boundary of Anthropology and Literature in Impasse of the Angels and The Hour of the Star”. In “An Aesthetics for the End”, edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, 18 January. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/exploring-narratological-tools-at-the-boundary-of-anthropology-and-literature-in-impasse-of-the-angels-and-the-hour-of-the-star-by-yash-chitrakar/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).