Pixelated Game Over screen on an oversized PAC-MAN arcade machine. Photo from Unsplash.

In his 1986 New York Times article, “Storytelling Among the Anthropologists,” anthropologist Richard A. Shweder made a canny observation about what makes for a good ethnography. He said those anthropologists who use casuistry may be the best practitioners of the craft. By this he didn’t mean to conjure images of medieval legal experts who utilize specious reasoning to justify their interpretations. Rather, he meant casuistry in a more positive sense, to indicate that anthropologists must figure out from which perspective an ethnography had to be written and learn to take others’ points of view.

Reading this intervention from the 1980s in the 2020s it seems to me that Shweder craftily avoids the old debate as to whether anthropology strives to articulate universals or to respect and uphold difference. His argument also allows us to take a needed break from countering accusations of cultural relativism, navel-gazing self-reflexivity, and the selective/ interpretative/ exclusionary nature of ethnography. His words capture the aspect of anthropology as one of nimble play, “adroit rationalization,” with play being the most serious thing an anthropologist can do.

When I embarked to teach “An Aesthetics for the End” for the School of Criticism and Theory at Cornell in the Summer of 2025, my goal was to open the anthropology of climate change and the Anthropocene to the possibility of approaching the idea of the end playfully. I was interested to explore my sense that a recent uptick of films about individuals confronting the end of the world—Melancholia, This is the End, Don’t Look Up—suggest new ways of aesthetically imagining “the end.” The films present the opportunity to feel, imagine, posit possible scenarios and moods, even play with the idea of the end. I was struck by the divergence between these films’ aesthetic approach, and my fellow anthropologists’ explorations in our writings on climate change and the Anthropocene, where we consider “the end” as a scientific fact, an intellectual puzzle or even a political or ethical imperative. In the course I wanted to explore whether anthropology could be opened to a more ordinary, even playful possibility of the end, combining anthropological writings and ethnographies with philosophy, social theory and Black Studies to bring about this encounter (see syllabus here).

The majority of the students registered for the summer course were English or Comparative Literature graduate students. In addition, there was an artist, a Sinologist, a student of Performance Studies and another of Music. With only non-anthropologists in my course, I had the lovely surprise of being reminded of the puzzles and pleasures of reading ethnographies. And I was reminded of Shweder’s understanding that all good ethnographies embed the play that anthropologists undertake in writing them; that is what makes them good to read.

Nowhere is this insight more evident and nicely exposited than in the essays a number of the students agreed to write for this curated collection on the themes of the course. The writings in this collection are attentive to the end in many different senses. We have ordinary ends, as in the end of a musical score or the end of a commodity’s life as waste; we have historical ones, such as the end of a period of colonial rule; some explore the anxiety expressed in prophecy or in painting that the end of the world will be a gigantic deluge; and others explore art as giving different, even distressed orientations to environmental devastation other than that of alarm.

Most intriguingly the essays illustrate the playfulness the ethnographies sparked in their readers, encouraging them to look about themselves more curiously, examining their experiences as an anthropologist might, as suggestive of a movement or trend in the world; to borrow a concept or two from a radically different context than the canonical ones to which they were accustomed to apply to their textual, visual, or sonic analysis; and, to delve into anthropological debates to see what they could draw from them and contribute to them in whatever small way.

In turn, this varied engagement with ethnography stands to provide useful insights for anthropology on the work it does beyond its own shores. Here is one: several of the writings treat ethnographies as genres. These are books I know well for having read and taught them many times and yet they felt new to me for being treated as such. Anthropologists such as George Marcus have long maintained that while ethnography is a genre, it is silent about its rhetorical style so as to enhance its claim to objectivity (Marcus 1980). Steven Webster maintains that ethnography has actually not aspired to be a genre but to a naive naturalism to suggest an immediacy between observed reality and its description (Webster 1986). Furthermore, this naturalism developed in contradistinction to the genre of social realism of the nineteenth century novel.

I provide this schema of a past debate within anthropology to show to what extent when anthropologists take up the issue of ethnography as genre, they are concerned to name and characterize it. What the collected writings here show instead is that to treat ethnography as a genre is not to identify or name its style once and for all. It is to affect a strategy that allows ethnography to get into conversation with other writings to see how they work together or not and towards what ends. This juxtaposition, I have found, is profoundly playful. Let me briefly sketch the interesting end time themes and engagement with anthropology in the contributions.

Yash Chitrakar’s “Exploring Narratological Tools at the Boundary of Anthropology and Literature in Impasse of the Angels and The Hour of the Star” is the work of a student of English. In bringing together Stefania Pandolfo’s ethnography Impasse of the Angels (1996) with Clarice Lispector’s novel The Hour of the Star (1997), Chitrakar offers a perspective on the question of whether ethnography is a genre or not. He shows how Pandolfo (and Lispector) illustrates “formal qualities that are usually found in fiction,” which has the effect of showing the “irreducibility/unknowability of the other.” Again, the emphasis is not on identifying the genre and its conventions but rather on the writing and whether these pieces have their desired effect on the reader. Chitrakar suggests, it does not matter whether one is an ethnography and the other a piece of fiction: each lays a claim on showing how difficult it is to live and die with others and on rendering this difficulty through words.

Another contributor who engages Stefania Pandolfo’s Impasse of the Angels is Anantaa Ghosh, student of Comparative Literature, in her submission titled “Spirits in Suspension and the Postcolonial ‘Barzakh’ in Kashmir.” It explores how one is never done with colonialism even in the aftermath of colonialism. She directly engages one of Pandolfo’s ambitions, that concepts from the Moroccan qsar (village) be used to “act as epistemological and aesthetic guides in a hermeneutical journey” (Pandolfo 1998, 6) to displace “the categories of classical and colonial reason and open a heterological space of intercultural dialogue” (Pandolfo 1998, 5). With that purpose, Ghosh uses the Islamic eschatological concepts of ruh (soul) and barzakh (purgatory) as deployed in Impasse to render the texture of another place than Morocco. Ghosh shows how the Kashmir of Haidar, the filmic adaptation of Hamlet by the Indian filmmaker Vishal Bhardwaj which he explicitly locates in contemporary Kashmir, is a terminus where lost souls abound unmoored from their bodies. This comes with other important observations on colonialism without an end within Ghosh’s writing.

Jo Gao’s “Waste & Hong Kong Post/Coloniality in Chungking Express” is another contribution examining film, specifically Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, pointing out how waste litters the surface of the film. This may be too easily seen as a metaphor for the disposability of Hong Kong, the setting of the film, by the British, referring to the British transferring administration of the territory to China at the end of its 99-year lease. However, Gao resists this reading. Drawing on the field of waste studies, which includes a considerable number of anthropologists, she shows how the waste is front and center in the film. This, in her reading, does not so much indicate disposability as durability: waste is here to stay. This eschewing of metaphoricity for materiality is put to good advantage by Gao to excavate terraforming in Hong Kong and its environmental legacy, thereby providing an important gloss on a classic film.

Along with Ghosh and Gao, Elisa Di Piero focuses her attention on the visual as the means to explore the interplay of the end and endlessness. In her contribution, Di Piero examines “Borrow a Glimpse of the Future,” a painting by the Taiwanese artist Zheng Chong-xiao. She points out the connection between Chong-xiao’s landscape and other contemporary landscapes in the Sinosphere that re-interpret traditional Chinese landscape paintings to address environmental themes. But whereas the older masterpieces intimate the eternal, the artistic reproductions, including “Borrow a Glimpse of the Future,” tend to emphasize anxieties for the future. Di Piero provides a virtuoso description of the painting to make her arguments, reading anthropologist Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency to good effect. She shows how Chong-xiao’s commitment and immersion in the tiniest details of his artwork functions to give agency to the artwork so as to make more poignant its environmental message. Di Piero shows Chong-xiao to be painting subjects, such as icebergs, which once expressed magnificence and permanence, but now signals the fast onset of global warming through its melting.

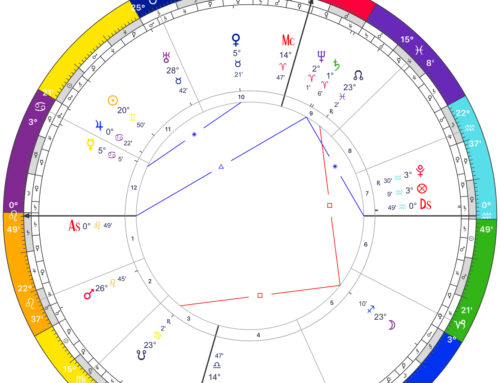

This image of the world ending in deluge resonates with Kam Tou Pang’s “The Indifferent Astrologer and the Worrying Aunt in the Face of a Rumored Earthquake,” an autoethnographic approach to the anthropology of rumor. Pang tells us what he did to assuage his aunt worried that Macau, where she lived, would be hit with a rumored tsunami following a rumored earthquake. Pang shows us that rumors having to do with environmental crisis seem to not carry the same affective punch as, say, that of a possible war, despite the contagious quality of rumors as a genre of communication. Moreover, rumors of such events may be promulgated by manga and anime as much as conventional news media or social media. This suggests that we still need to parse the relationship between genre and social media. Pang’s essay also reminds us that indifference to rumor need not indicate a blindness to worry or numbness to suffering but a different modality by which one engages in care.

Hannah Waterman’s “Beyond Feminine Endings, a Masochistic Listening Practice” returns us to ordinary endings by taking us to the ending of Beethoven’s widely beloved Symphony No. 9 and its feminist reading by Susan McClary, who argues that the symphony has the structure of a rape. Waterman elaborates how she is shaken by this analysis. To understand McClary’s interpretation and her response to it, Waterman explores the western structure of listening appreciation on which the interpretation is based. Drawing on Deleuze’s writings on masochism, she suggests a different mode of listening with a different effect: a queer theory of listening that is more interested in giving pleasure than in receiving it.

The last contribution in the collection is Amanda Macedo Macedo’s “Rio de Niebla: Listening, Response-Ability, and the Disappearance of Mexico’s Last Glacier.” She draws on the writings of Donna Haraway, Karen Barad and Anna Tsing to contend that the responsibility for tending to the environment is not comprised of a discrete set of imperatives but is a process of coming to understand one’s entanglements with the world. Macedo Macedo unfolds not just an artist’s and a glaciologist’s individual understanding and affective response to the last glacier in Mexico and its possible loss, but also their interrelation and effort to take each other’s points of view. Macedo Macedo concludes: “By attending to sound, territory, and disappearance, Ximena’s work offers what might be called an aesthetics for the end—grounded not in mastery or detachment but in proximity, responsibility, and the willingness to be transformed by another’s ways of knowing.”

This collection of essays stands to remind anthropologists that the way to make our mark within debates of concern isn’t only through seeking to be timely, such as by writing op-eds in newspapers, but through the effort of putting ourselves in conversation with other disciplines. In learning to appreciate, maybe even love other ways of deliberating and asking questions, as much as we love our own, even as we critique them, we may better fight for one another’s existence.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Kathryn Elissa Goldfarb and her team for their help in facilitating the publication of this collection on AES Online. My deep gratitude to Carolyn Rouse for organizing such an exciting and scintillating summer program at the School of Criticism and Theory. Finally, to the students of “An Aesthetics for the End,” thank you for your intellectual curiosity and boundless energy in volunteering to write for this collection. You were a joy to spend a summer conversing with.

References

Marcus, George. 1980. “Rhetoric and the Ethnographic Genre in Anthropological Research.” Current Anthropology 21(4): 507-510.

Pandolfo, Stefania. 1997. Impasse of Angels: Scenes from a Moroccan Space of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Shweder, Richard A. 1986. “Storytelling Among the Anthropologists.” New York Times 21 September.

Webster, Steven. 1986. “Realism and Reification in the Ethnographic Genre.” Critique of Anthropology, 6(1): 39-62.

Naveeda Khan is Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her publications include Beyond Crisis: Re-evaluating Pakistan (2010), Muslim Becoming: Aspiration and Skepticism in Pakistan (2012), River Life and the Upspring of Nature (2023), In Quest of a Shared Planet: Negotiating Climate from the Global South (2023) and Dream’s Navel: Reading the Bengali Modern Classic Akhtaruzzaman Elias’ Khwabnama (forthcoming). Her personal website is https://www.naveedakhan.org/.

Cite as: Khan, Naveeda. 2026. “Introduction: An Aesthetics for the End”. In “An Aesthetics for the End”, edited by Naveeda Khan, American Ethnologist website, 18 January. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/introduction-an-aesthetics-for-the-end-by-naveeda-khan/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).