“Meghna, are you going to share today?” asked at least one classmate every week of my second semester of fieldwork at the postgraduate program in counseling psychology (colloquially termed ‘MPCO’) at a university in Bengaluru, a major city in southern India. The two hours after recess every Thursday in this semester were reserved for the professional development (PD) course. I was granted access to one of the four PD “batches” (groups) by the program coordinator, who led the batch I was part of. The objective of the course was to help trainees cultivate self-awareness and reflection—skills crucial to a career in counselling. Every week, students read out the reflective essays they had written about the assigned themes. The first theme was branching points, or moments that mark a critical juncture in a person’s development. The second theme was family.

Week after week, I remained silent, until there was a topic that I couldn’t avoid. When I finally shared my essay, inaugurating the theme of health and body image, something cracked open. I spoke of my depression and the slow arc of recovery that followed. Armed with my psychiatrist’s diagnosis and concepts, I went on to recount my suffering and recovery in the pages of my PD essay, using words like relapse and cognitive impairment. I had “to blend art and science,” as the trainees often described counselling. As Ruth Behar (1996, 7) once wrote of ethnography, it was “neither romance, nor lab report, but something in between.”

A leaf out of the author’s reflective essay on health for the Professional Development course in the counselling training program. Photo by Meghna Roy.

In the paradoxical tightrope of participant observation, I had to be my authentic self to qualify as participant. Writing the essay had taken weeks of inner wrestling, but the act of reading it aloud rendered the anthropologist in me porous. My classmates’ genuine sustained curiosity about my life turned the classroom into a transformative space. There were a couple of minutes of silence after the reading. Then Sharon, a classmate I barely knew in a class of sixty trainees, spoke. She acknowledged how hard it must have been for me to get out of bed and turn up to campus every day. She said, “I would look for Meghna in class every day; sometimes when she was not around, I wondered why.” I had once wept with Sharon when she shared her reflection on growing up in an abusive household, and hugged her that afternoon before leaving for home. Now, she held space for me. Another classmate, Priya, resonated when I lamented over “the version of my life that my mind conjures up.” The psychological term for this phrase is distorted reality. Then Priya recounted her journey with depression from a few years past when things were not as bad as her mind perceived them to be. These were moments of intervention, into others’ lives and into mine.

To be in the field is to be vulnerable. While some ethnographers’ vulnerability is connected to external precarity, mine was more about internal rupture. I always knew my way through a crowd of rickshaws, motorcycles, and cars on the street outside campus with barely any sidewalk, but I was new to prying my soul open to a room full of trainee counselors.

Another moment that crystallized this inner work was a simulation exercise in which I played the role of a client to eleven counsellors. I could stop the session if it overwhelmed me, but I did not. Instead, something unexpected happened: I began to draw from my own emotional life—not as an illustrative anecdote, but as a mode of relating. The boundaries between observer and participant collapsed. Vulnerability no longer ran in one direction; it became mutual, unsettling the presumed neutrality of the researcher.

On this day, unusually hot for February, the air conditioning had broken down in all skills labs on our floor. My cohort of ten in the multicultural counseling skills course relocated upstairs to a boardroom on the sixth floor, which is dedicated to doctoral researchers. For the ensuing simulation I sat at the center of the room, surrounded by a semicircle comprising the instructor, Anitha, and her trainees. Anitha described my chair as the ‘hot seat’ where doctoral candidates were seated to defend their proposals as hounding faculty members surrounded them. Despite the blasting air conditioning, my armpits dripped with sweat. I was nervous but motivated by the trainees’ careful attention to each word I said.

I was meant to improvise a fictional case: a woman in her twenties, living in Bengaluru for her job while her parents stay in her hometown. Her father has taken to alcoholism. Her mother feels intimidated by his behavior. It was, uncannily, my story—with one detail altered. In real life, my mother hadn’t been intimidated by my father’s drinking; she had been embarrassed. The rest was painfully familiar. As I ‘performed’ the case, I brought my mother’s shame into the room. I spoke of moral failure, guilt, and the social stigma that surrounds alcoholism in urban Bengali families like mine. My peers applauded my ‘acting.’

Everyone participating in a simulation had the freedom to live their truths without having to fully expose themselves. For the first time, I was able to voice my feelings about my father’s illness to someone besides my therapist. I shared the loneliness, the helplessness, the wish that his job as a cop had been easier. Their responses offered a picture of alcoholism among middle class fathers in urban India. Many of them knew alcoholics—one even had an alcoholic dad. It humanized my experience, taking the lid of self-pity off my pain. Yes, my father is now far better. There is no cure. He has occasional relapses. The roleplay gave me something therapy had not: a collectively held space, one where the intentions of every participant were aligned in the service of ‘simulated’ care.

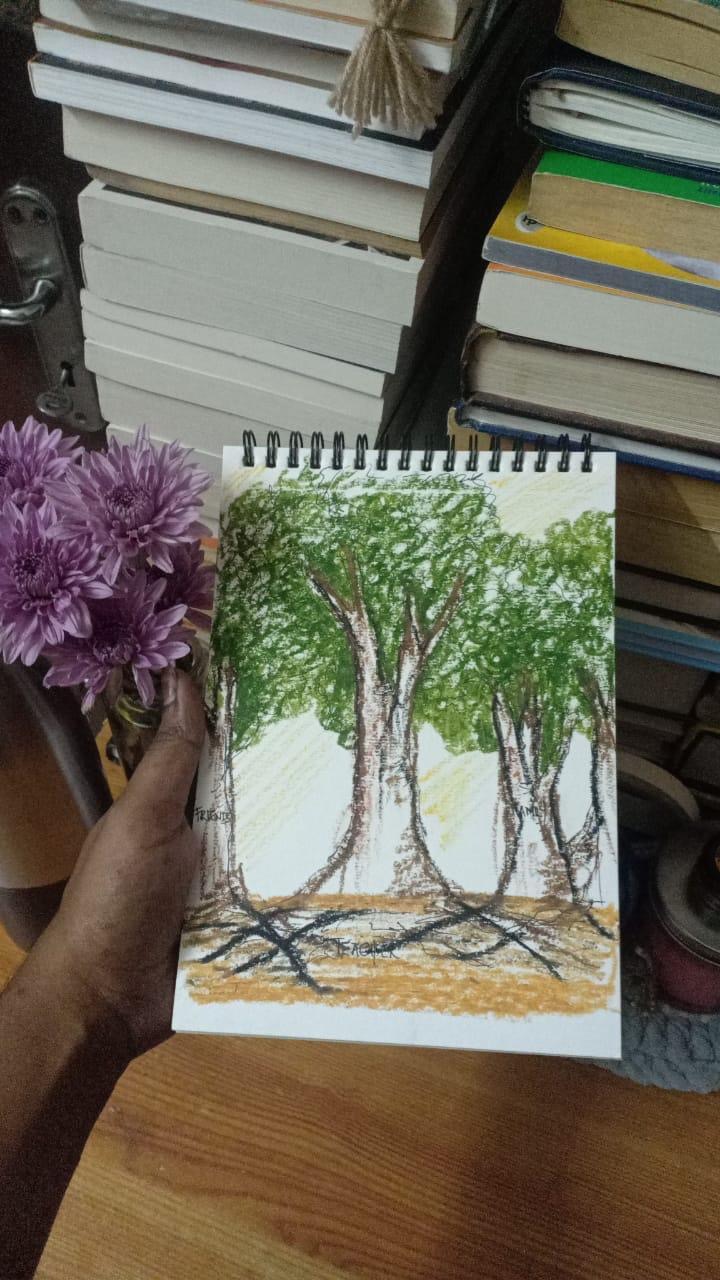

Sketch by another participant in the group discussion on the mental health of doctoral researchers. Photo by Maria Viju.

This reflexive posture did not just generate ethnographic insight—it changed me. I found myself echoing the hesitations of the very trainees I was studying. Our shared discomfort— about how much to say, how much to feel—became a point of connection. As psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb writes in Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, a book popular among MPCO students, “How much do we want to know? How much is too much?” These questions trailed me beyond the classroom: into hallway conversations, lunch breaks near the campus gate, and late-night chats in my apartment. Each encounter became an invitation not just to listen, but to participate in the vulnerable labor of self-work. Fieldwork, I came to realize, wasn’t simply about collecting stories; it was an unfolding process of being intervened upon, by the field, and by others.

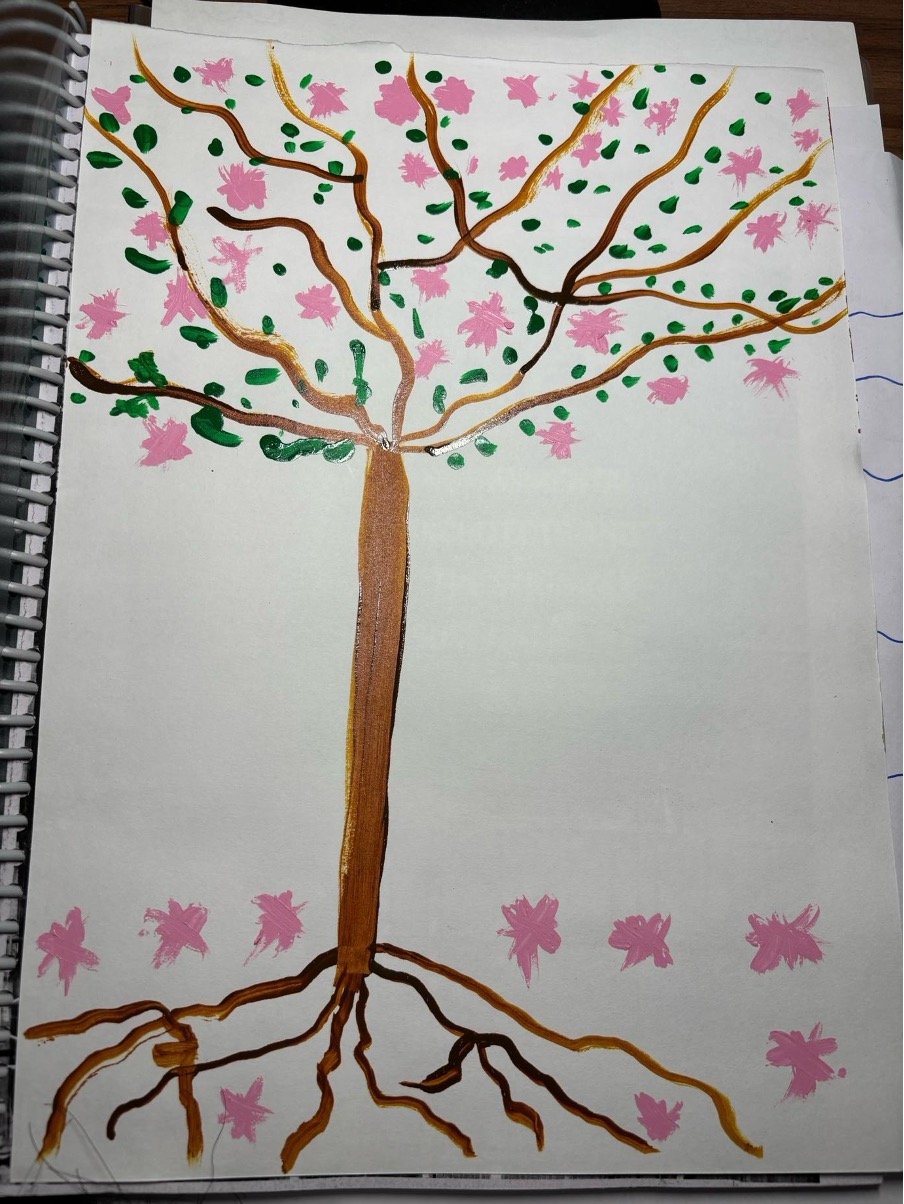

I began participating in group discussions on the mental health of doctoral students, sessions usually reserved for “subjects,” not researchers. One session invited participants to sketch their PhD journeys as trees. As I drew, I felt the field folding in on me. Not only were its arms open to observation, but also for intervention. What happens when the researcher is vulnerable too? When their soul, too, is being worked on?

The author’s impression of her PhD journey at a group discussion led by counselling trainees. Photo by Meghna Roy.

As a researcher, I could now externalize my self while being emotionally intimate with my ‘subjects’ (Behar 1996). Fieldwork broke me, and then put me together. It exposed me to psychological distress, a temporary exposure to heal my wounds, just like in psychotherapy. I imagine these wounds as collateral damage of the human condition. Fieldwork demanded that I not just document others’ vulnerability but inhabit it. In doing so, it brought me face-to-face with parts of myself I had not yet fully met. In this deceptively familiar field site, I encountered myself anew.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to all participants in this research and to Keir Martin for his mentorship.

References

Behar, Ruth. 1996. The Vulnerable Observer. Beacon Press.

Gottlieb, Lori. 2019. Maybe You Should Talk to Someone. Amaryllis.

Meghna Roy is a medical and psychological anthropologist with an interest in epistemologies of healing. She completed her BA, MA, and MPhil in Sociology before joining the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo, where she is a Doctoral Research Fellow on the comparative ethnographic project ‘Shrinking the Planet,’ funded by the Research Council of Norway.

Cite as: Roy, Meghna. 2025. “Blending Art and Science.” In “Anthropology that Breaks Your Heart: Loss and Found,” edited by Salwa Tareen, Magdalena Zegarra Chiappori, and Hosanna Fukuzawa, American Ethnologist website, 24 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/blending-art-and-science-by-meghna-roy/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).