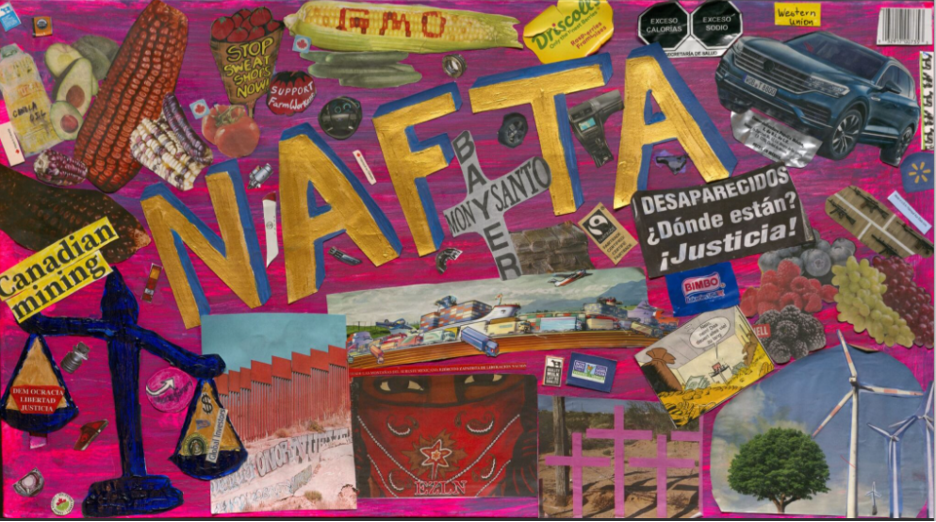

NAFTA collage made from different materials, including a snippet of a photo by Barbara Zandoval on Unsplash (Mexico-U.S. Border). Created by Alejandra González Jiménez.

President Trump’s tariff war has put free trade into the spotlight. It has become a day-to-day news item, a subject of academic panels, a topic of everyday conversations, and a spark reigniting nationalism. Yet for decades, the macro instrument of free trade has silently and ubiquitously governed the global economy through hundreds of agreements currently in force.[1] This collection of essays focuses on one of the most famous trade agreements: the North American Free Trade Agreement, known as NAFTA, and its successor, academically known as NAFTA 2.0. For three decades, NAFTA has re-stitched and fractured Mexico, Canada, and the U.S., while interconnecting roughly 500 million people.[2] Initially assembled to mark thirty years of NAFTA, this collection now aims to refocus attention on what is at stake in defending, replacing, or reconfiguring this free trade agreement, given the uncertainty surrounding what will happen after 2026, when NAFTA 2.0 is scheduled to be renegotiated.

The essays offer glimpses into worlds engendered by, or indirectly shaped by, NAFTA. An anthropological approach offers an understanding of this free trade agreement (FTA) beyond the frameworks, parameters, and language of economics. What is free trade beyond the quantifications of trade deficits, billions of dollars’ worth of trade and investment, retaliatory measures, and the number of manufacturing jobs created or lost? What is NAFTA when we examine it as a whole instead of looking selectively at a particular sector to gauge its (in)effectiveness? If we direct the analytical gaze to processes and realities deeply entangled with NAFTA—yet left outside the usual frameworks and scales of analysis deployed by its defenders and critics—what is at stake socially, environmentally, economically, and politically in maintaining, defending, or gradually breaking apart the North American geo-economic region?

Stitching the North America Geo-Economic Region

NAFTA was signed in 1992 and implemented in 1994. It was the first of its kind and became a blueprint for subsequent FTAs around the globe. At the time, it interconnected more than 300 million people, creating the largest transnational free-trade zone in the world. Its scope was also broader than previous FTAs: in addition to liberalizing agriculture, manufacturing, and automobile production, liberalization extended to services, investment, telecommunications, mining, and intellectual property. Labor and environmental concerns were addressed in side agreements. NAFTA was also the first FTA to include a provision to track pollutants at the facility level (Lepawsky 2023). Its successor, NAFTA 2.0, additionally includes mechanisms to support workers in particular sectors in their effort to fight for freedom of association at the facility level.

NAFTA was a key piece in the multilateral free-market world order emerging in the 1990s. Supranational organizations—International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization—organized the economy at the macro scale and directed economic development within nation-states under the paradigm of neoliberal capitalism implemented through the structural adjustment programs outlined in the Washington Consensus. In Mexico, Canada, and the U.S., NAFTA solidified, accelerated, expanded, deepened, and naturalized an assemblage of neoliberal policies, ideologies, modes of governance, and visions of how the world ought to be.

NAFTA is a late 20th century free-market economic instrument, yet the principles of free trade are based on imperial and settler visions of the world (Locke [1689] 1964; Lowe 2015; Ricardo [1817] 1971]; Smith [1776] 1991). Free trade was vital to reconfiguring sixteenth-century colonial relations of subjection and extraction. In the nineteenth century, free trade was key to enhancing the British Empire’s rule and coercion while transforming it into an economic power dominating the global economy (Gallagher and Robinson 1953; Grady and Grocott 2018). In this context, free trade was a permutation of imperialism, politically functioning to create and integrate regions of trade and of accumulation for “British capital overseas at minimal cost to the British state [through] imposition of policy prescriptions favorable to British trade” (Gallagher and Robinson 1953, 5; Trouillot 1988).

Similarly, NAFTA has created and enhanced infinite possibilities of capital accumulation by stitching together the U.S., Mexico, and Canada through a shared economic instrument. Simultaneously, NAFTA has worked to secure U.S. interests in the North American geo-economic region. For instance, in twenty-five years, the U.S. government has never lost an investor-state dispute settlement case against corporations, unlike Mexico and Canada. NAFTA functions as a form of “soft power,” as the 2025 tariff war has demonstrated, when Mexico and Canada went the extra mile trying to defer tariffs. The most notable example was Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo’s decision to increase the militarization of the Mexico-U.S. border at the request of President Trump—a questionable response given the military and cartel violence that already characterizes this area (Paley 2025).[3] NAFTA, in this sense, is instrumental for U.S. domination in the Americas (Grandin 2021).[4]

NAFTA is a form of what anthropologist Eric R. Wolf has called structural power, as it “not only operates within settings or domains but also organizes and orchestrates the settings themselves [shaping] the field of action [constraining, inhibiting or promoting] what people [or nation-states] do, or cannot do […] This is not purely an economic relation, but a political one as well: it takes clout to set up, clout to maintain, and clout to defend” (1990, 586-587). NAFTA as a form of structural power, operates across scales and is instrumental in creating infinite possibilities for primitive accumulation (Marx 1990) and accumulation by dispossession (Harvey 2004) by stitching together unevenly located nation-states and by reconfiguring inequalities between and within them.

Legacies

Imperial legacies running through contemporary global free trade are visible in the central role corporations play in governing lives, livelihoods, and deaths. Corporations such as the English and Dutch East India companies, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the Royal African Company were crucial in securing imperial power in the colonies (Barkan 2013; Rajak 2013). Geographer Joshua Barkan shows how, in the seventeenth century, corporations gained legal recognition by arguing that they benefitted the common good through their “ability to provide for health, welfare, and security of the population” (Barkan 2018, 8). Such a pursuit has endowed corporations with the power to “govern life through the extension of the [liberal] law as well as through legally authorized suspensions, privileges, and immunities from law” (ibid). The pursuit of “public welfare” —a floating signifier— “can include dramatic powers up to and including transgression of the legal order [with] the potential to threaten not only the political existence of the very populations they are designed to save but their biological existence as well” (ibid).

Under the neoliberal world order, corporations have been endowed with the power to rule over labor, livelihoods, the environment, and people’s well-being. Fifty years of neoliberalism— marked by disinvestment in public expenditure in education and healthcare, privatization, structural adjustment programs, labor precarity, and waves of economic crises—have redefined notions of the “public good.” Security, welfare, and health are equated with a job that can only be created through corporate investment, while the government’s role is to remove any barriers. NAFTA, alongside corporations, continues to reproduce the myth that free trade allows prosperity to trickle down regardless of the dangers to the biological existence of populations—workers’ sick and poisoned bodies— the planet, and even political life, given that NAFTA and corporations are among the most undemocratic elements of so-called liberal democracies.

NAFTA is an iteration of how liberal law continues granting corporations legal privileges and immunities. The investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS, NAFTA Chapter 11 and NAFTA 2.0 Chapter 31) provides a legal framework not only to shield corporations from liabilities but also to allow them to sue the three governments in the North American geo-economic region. By arguing that policies protecting public health, the environment, or the public interest can cause damages to their investments, corporations have forced Mexico and Canada to pay millions of dollars in penalties and fees (Frens-String and Velasco 2016; Sinclair 2015, 2021). “Damage,” in this context, includes projected future profit.

Legal confrontations, however, do not mean that NAFTA engendered an antagonistic relationship between corporations and governments. Instead, they mutually reinforced the rationale for each other’s existence. Under neoliberalism, a strong state is one that can attract investment to provide employment in the formal economy, thus reproducing the equation of “well-being” with a job.

Free Trade Development

In Mexico, NAFTA re-entrenched the evolutionary modernization theory-myth that industrialization, urbanization, and wage jobs in the formal economy would create development and lift people out of poverty. The vision was that NAFTA would propel the country from a “Third World” economy into a “First World” economy, where instead of “exporting people,” Mexico “would export goods.”[5] Mexicans would consume like people in Canada and the U.S. Mexico’s transformation into a hub for export production and a site for accelerated accumulation, however, ultimately spiked migration.[6] Free trade jobs were and continue to be precarious, yet are praised as a better option than unemployment or employment in informal economies. The celebratory account surrounding free trade jobs obscures the fact that many people who work in export and service economies must create a second (or third) source of income because their jobs alone are not enough to make a living.[7]

The consensus among defenders of free trade, even those in progressive camps, is that precarious jobs are better than no jobs.[8] Progressive defenders argue that wage increases, along with the new compliance mechanisms found in NAFTA 2.0—which provide workers in some sectors with legal mechanisms to fight for freedom of association and better working conditions—represent the path to improving the lives of working class people. Yet, these arguments conveniently silence the patterns of inequality, dispossession, and exploitation intrinsic to the history of economic development in the three countries, while naturalizing low production costs for corporations at the expense of people and the environment.

NAFTA also normalized a division of labor and consumption characteristic of late twentieth century globalization: the so-called Third World, or “developing world,” became a site for producing cheap commodities to sustain the rampant consumption that defines lifestyles in the “Global North.”

Silences

NAFTA has thrived through several and multivalent silences. A notable silence concerns how NAFTA fits within the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt. The popular claim that NAFTA “sent jobs to Mexico”—voiced in 1992 in the United States by organized labor and politicians such as Ross Perot and repeated frequently since, including in 2025 by President Trump and Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers (UAW)—has made Mexico the scapegoat for several problems in the U.S. This claim, however, omits the fact that the 1970s neoliberal restructuring destroyed the conditions that had once made certain manufacturing jobs a path of social mobility in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

NAFTA accelerated a process premised on the assumption that the next stage of accumulation would involve a shift from an industrial to a post-industrial society (Bell 1973). Instead of manufacturing, services, information, and knowledge (Dudley 1994; Walley 2013; Zukin 1991) would organize the social relations of production and reproduction. The 1970s neoliberal restructuring also undermined the collective power of organized labor by relocating segments of production to right-to-work states in the United States, Puerto Rico (Abedian 1995), and along the Mexico-U.S. border (Fernández-Kelly 1983; Peña 1987). The claim also omits how the 1980s fragmentation of production and automatization reduced the number of industrial unionized jobs (Graham 1995; Woodman 2018).

NAFTA expanded Mexico’s economic development model based on export production inaugurated in the mid-1960s by the maquiladora program. In the wake of NAFTA, textile production (Collins 2003), car assembly, auto-parts manufacturing, and other forms of industrial assembly relocated to Mexico. Yet the jobs created in the niches where NAFTA is enacted day to day in Mexico—manufacturing auto parts, furniture, and textiles; assembling cars and medical equipment; mining; large scale agriculture of tomatoes, berries and avocados; jobs at Wal-Marts, Home Depots, call centers, and in transportation/logistics and financial services such as money transfers—are hardly the kinds of jobs that inspire nostalgic longing in the U.S. and Canada.

Silences obscure how free trade thrives through precarious working and living conditions in all three countries and by antagonizing working classes. Except for a handful of moments in NAFTA’s history (Bacon 2004; Crawford 2025; Healy 2008), this claim has prevented solidarities across borders and labor movements across sectors.[9] Instead, it ignites nationalisms that serves right-wing politics while stirring up racist sentiments in the United States that have long characterized Mexico-U.S. relations.

But NAFTA has also thrived through silencing processes that, at first glance, seem unrelated or only directly connected to it. It is to these silences that I now turn, in the spirit of re-focusing what is at stake in defending NAFTA and/or in projects seeking to replace it.

A Foretold Death

NAFTA, globalization, and neoliberalism have, since the 2008-09 financial crisis, become objects of critique by groups that have long benefited from free-market economics, globalization’s division of labor, and modes of extraction. The epitome of such critique was President Trump’s 2018 remark that “NAFTA is the worst trade deal.”

The critique of neoliberal globalization is not unfounded. After fifty-two years of neoliberalism—and thirty years of NAFTA—it has become impossible to contain, tame, or silence the contradictions and violence inherent to capitalism, especially in this free-market form, and as it plays out in the lives of the majority of people living in the North American geo-economic region.

To grapple with what has been at stake for at least thirty years, let us return to an earlier critique. Since the 1990s, NAFTA has been vehemently opposed, criticized, and confronted through armed rebellion and numerous mass street mobilizations worldwide. The Zapatista uprising on January 1, 1994—the day NAFTA came into force—was followed by the anti-globalization and alter-globalization movements contesting neoliberalism and free trade globalization.

At the time, Los Zapatistas declared “NAFTA is death” (cited in Gutiérrez 1998, 146). Their foreboding centered on the end of land redistribution programs, new legal mechanisms to dispossess people of their land, and conflicts over natural resources—all with devastating effects on historically marginalized communities, especially Indigenous peoples.[10]

“NAFTA is death” helps us think about the current moment, in which any critique of free trade is typecast as protectionism and taken to be aligned with right-wing politics. From the vantage point of 2025, Los Zapatistas’ declaration can be interpreted as a foreseen death. Death, however, has taken many forms. It is visible in those people who die trying to cross the Mexico-U.S. border to escape NAFTA’s precarious economic and violent social conditions—including the ways free trade has intersected with and fueled violence by the state, corporations, and cartels. Death exists in the killings and disappearances of activists, dissidents, journalists, migrants, human rights defenders, and ordinary people. It is present in the femicide of maquiladora workers (Wright 2006), and in the killings of people defending their territories against dispossession by corporations and cartels (Paley 2014). Death is also evident in those killed by the legal and illegal guns flowing from the United States into Mexico that have fuelled cartel violence (Muehlmann 2024).[11] NAFTA as death is visible in the bodies of people slowly consumed by diabetes (Gálvez 2018), and by the chemical exposure and pollution created by commodity production (Funary and De la Torre 2006; Zlolnisky 2019).

NAFTA as death is also manifest in the pollution generated by mining, agribusiness, manufacturing, and energy extraction. Death is tangible in the desertification caused by excessive water extraction and the use of chemicals, pesticides, and fertilizers to grow seasonal fruits and vegetables year-round. Their compounding effects include the loss of biodiversity. Death is embedded in the ruling that prohibits Mexico from halting the importation of GMO corn, which has the potential to destroy millenarian corn landraces and their surrounding ecosystems.[12]

Grappling with how NAFTA has sown death must be part of any deliberation assessing free trade broadly speaking—and of imagining what may come after NAFTA. As Mexico and Canada prepare to renegotiate NAFTA 2.0 in 2026 and simultaneously confront the possible death of this free trade agreement, their plans for economic development tend to reproduce the myth that free trade is the path to prosperity and well-being at the household, national, and transnational scale.[13]

Recent plans to overcome the tariff war in Mexico and Canada reveal the impossibility—both structural and imaginative—of rethinking and implementing alternative ways to organize trade, economies, and well-being beyond the grip of the corporation, rampant commodity consumption, and capitalism. They reinscribe the postwar belief that equates manufacturing jobs with “good jobs,” while reproducing the model of production dependent on extraction, environmental destruction, and labor exploitation. Although the effects of tariffs are acutely felt across the North American geo-economic region—especially among people whose jobs are tied to free trade and those living in precarious conditions—such responses cannot be normalized as adequate to the current moment of climate catastrophe, labor-rights erosion, and attacks on social reproduction.

The impossibility of reimagining alternative interconnections, trade economies, and relationships runs across the political spectrum in Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Revisiting the Zapatistas’ critique can refocus the stakes of reproducing the same model of development. Thirty years of NAFTA—and similar free trade agreements—that have led to worsening livelihoods and accelerating climate catastrophe must make us wary of continuing down the same path.

The Collection

The essays in this collection offer a glimpse into the multivalent worlds engendered and shaped by NAFTA. Mostly written from the vantage point of Mexico, they illuminate free trade’s impacts on everyday life—how it intersects with, co-exists with, or fuels socioeconomic, cultural, and political processes particular to specific places. The themes explored are varied, though not exhaustive. Together, they offer a clear view of the impacts of free trade.

Four essays in this collection address NAFTA and commodity production. Zlolnisky and Fischer-Daly show how NAFTA’s agribusiness expansion has meant massive extraction of water with detrimental effects on workers’ social reproduction. Fitting examines the GM-corn regime and the challenges it poses to Mexico’s project of food sovereignty, along with the resistance to it and to transnational corporations. This piece illustrates the legal battles waged to stop U.S. GM-corn importation to Mexico. Lyon, by contrast, explores the interplay between free and fair trade, and the challenges that disruptions to free trade pose for fair-trade systems. Tetreault sketches how NAFTA accelerated the extraction of minerals in Mexico through mining.

The next seven essays show sites and processes that, while deeply entangled with free trade, are often left out of its normative understandings. Gálvez traces the connections among NAFTA, undocumented migration to the United States, and border militarization: NAFTA pushed Mexicans out, yet border militarization has since caged them in. Muehlmann illuminates how NAFTA is intrinsic to Mexico’s violence and disappearances. Escobar González reconstructs a history of financial maneuvers that bankrupted Mexico yet were deemed necessary to create NAFTA.

Hernández Corchado offers another view of Mexican migration to the U.S., showing how young Mexican men articulate their experience of having been expelled from Mexico to New York City through rock songs and social gatherings. Villegas Delgado focuses on a Zapatista mural painted in 2001 in New York City to reflect on the afterlife of the Zapatista uprising and its impact on local and transborder immigrant activism. Hunter-Pazzara interrogates the assumptions shaping NAFTA, showing how the myth of American exceptionalism has served to silence the dire situation of labor and unionism in the United States. Finally, my own essay reflects on a course about NAFTA taught to a generation of students in Canada who have come of age in the era of free-trade globalization.

This collection is a call for an anthropology of free trade. An ethnographic approach to free trade captures the local while simultaneously situating it across transnational scales and tracing historical and geographical interconnections. Such an approach attends to processes deeply entangled with NAFTA yet excluded from normative understandings. By making free trade its object of study, this collection offers a nuanced examination of how neoliberalism continues to evolve. This point is crucial, as the claim that neoliberalism is dead has gained traction. Neoliberalism is not dead; it is being reconfigured. Free trade is one site through which to observe this rearrangement.

Acknowledgements

I thank all the authors for their insightful contributions, my students at the University of Toronto and at Huron University College for helping me think through the ways in which NAFTA impacts their everyday lives while remaining enigmatic to most, and my interlocutors in Puebla who, over the years, have helped me understand local entanglements with, and fights against, free trade in Mexico. Finally, along with all the other contributors, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Katie Kilroy-Marac for her tireless support in getting this issue out and for her editorial finesse. Huge thanks to Melanie Ford and the AES Digital Content team.

Notes

[1] According to the World Trade Organization, there are 375 regional trade agreements in existence as of May 2025, many of which are FTAs.

[2] NAFTA 2.0 is known is the U.S. as the United States-Mexico- Canada Agreement (USMCA), in Canada as CUSMA, and in Mexico as T-MEC. NAFTA 2.0 was signed in 2018 and entered into force in 2020.

[3] According to U.S. President Donald Trump, Mexican soldiers at the border are there to stop fentanyl and “illegals” from entering the U.S. from Mexico. According to Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexican soldiers are posted at the border to stop the trafficking of fentanyl from Mexico to the U.S., and the trafficking of guns from the U.S. to Mexico.

[4] By foregrounding the imperial origins of free trade, I don’t mean to suggest that colonialism and imperialism are constant or static. Empire and colonial relations of subjection and domination are constantly evolving yet what remains constant is labor exploitation, extraction, dispossessions, and the (re)production of racialized Otherness (Coronil 1995; Mintz 1985; Ortiz 1995 [1947]; Wolf 1982).

[5] This is how Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who was Mexico’s president between 1988 and 1994, advertised NAFTA to the United States.

[6] Mexican migration to the United States continues to fluctuate. NAFTA caused migration numbers to spike, yet the 2008-09 recession caused numbers to fall. Cartel, military, and corporate violence against people—as well as environmental impacts caused by the climate catastrophe—also contribute to these fluctuations.

[7] For example, some of my interlocutors employed as logistics workers handling the distribution of auto-parts make piñatas or sell food on the street on their days off. Female autoworkers also make desserts to sell to their co-workers. Maquiladora workers living on the Mexico-United States border donate blood in the U.S. as a source of income (Comité Fronterizo de Obrer@s CFO).

[8] For example, this was an argument exposed by Paul Krugman in his piece “In Praise of Cheap Labor.” I heard a similar argument at the 2024 Third Tri-national Meeting on Labour Rights under CUSMA-USMCA-T-MEC in Toronto from labor activists and academics.

[9] See also “$4 a Day? No Way! Joining Hands Across the Border.

[10] NAFTA’s push to privatize communal land is part of the tragedy of the commons that has historically dispossessed people, in particular, Indigenous people in settler states—of their lands (Bianet Castellanos 2021, 13).

[11] The United States Supreme Court blocked Mexico’s lawsuit against U.S. gun manufacturers, which exempt them from any liability from cartel violence.

[12] NAFTA’s environmental destruction in Mexico is framed in the United States and Canada as the result of corruption and/or lax regulations. This framing, however, silences the class-based and racial geographies that have made Indigenous peoples of the Americas—as well as Black and Latinos in Canada and the U.S.—disposable in the pursuit of economic development (DiChiro 1998; Gilio-Whitaker 2019).

[13] President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo’s Mexico Plan (Plan México) aims at manufacturing commodities exported from China (shoes, furniture, steel, aluminum, solar panels, batteries, semi-conductors, and medical equipment) for exportation and for internal consumption, to counter the accusations that Mexico is the “back door” of Chinese commodities in the North American geo-economic region. Wal-Mart will open more locations to sell “Made in Mexico” products and build robotic logistics hubs. These are some of President Sheinbaum Pardo’s strategies to fend off trade conflict. In Ontario, premier Doug Ford proposed “Bill 5: Protect Ontario by Unleashing our Economy Act,” a controversial bill that has already put organized labor, First Nations, and environmental activists on guard. If passed, Bill 5 will allow the creation of “special economic zones” and mining projects in Indigenous territories, posing a threat to their sovereignty. Bill 5 further seeks to scrap The Endangered Species Acts and override any other existing environmental and labor laws and regulations in Ontario.

References

Abedian, Julia C. 1995. Exposing Federal Sponsorship of Job Loss: The Whitehall Plant Closing Campaign and “Runaway Plant” Reform. New York: Garland Publishing.

Bacon, David. 2004. The Children of NAFTA: Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Barkan, Joshua. 2013. Corporate Sovereignty: Law and Government under Capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bell, Daniel. 1973. The Coming of a Post-Industrial Society: A Venture into Social Forecasting. New York: Basic Books.

Castellanos, M. Bianet. 2021. Indigenous Dispossessions: Housing and Maya Indebtedness in Mexico. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Collins, Jane Lou. 2003. Threads: Gender, Labor, and Power in the Global Apparel Industry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Comité Fronterizo de Obrer@s. n.d. “Open Letter to the President of Mexico Felipe Calderón Hinojosa on the Fifteenth Anniversary of the North American Free Trade Agreement.” Cornell eCommons.

Coronil, Fernando. 1995. “Introduction.” In Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar, by Fernando Ortiz, ix–lvii. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2001. “Smelling Like a Market.” American Historical Review 106 (1): 119–29.

Crawford, Sean. 2025. “Will Trump’s Tariffs Be Good for Auto Workers?” Labor Notes.

Di Chiro, Giovanna. 1998. “Nature as Community: The Convergence of Environment and Social Justice.” In Privatizing Nature: Political Struggles for the Global Commons, edited by Michael Goldman, 120–43. London: Pluto Press.

Dudley, Kathryn. 1994. The End of the Line: Lost Jobs, New Lives in Post-Industrial America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fernández-Kelly, María Patricia. 1983. For We Are Sold, I and My People: Women and Industry in Mexico’s Frontier. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Frens-String, Joshua, and Alejandro Velasco. 2016. “Free Trade 2.0.” NACLA Report on the Americas 48 (3): 207–8.

Funari, Vicki, and Sergio de la Torre. 2006. Maquilapolis: City of Factories. Film. San Francisco: California Newsreel.

Gallagher, John, and Ronald Robinson. 1953. “The Imperialism of Free Trade.” The Economic History Review 6 (1): 1–15.

Gálvez, Alyshia. 2018. Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies, and the Destruction of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gilio-Whitaker, Dina. 2019. As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock. Boston: Beacon Press.

Grady, Jo, and Chris Grocott. 2018. “Introduction: The Continuing Imperialism of Free Trade.” In The Continuing Imperialism of Free Trade: Developments, Trends, and the Role of Supranational Agents, edited by Jo Grady and Chris Grocott. London: Routledge.

Graham, Laurie. 1995. On the Line at Subaru-Isuzu: The Japanese Model and the American Worker. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Grandin, Greg. 2021. Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Making of an Imperial Republic. New York: Picador.

Gutiérrez, Andy. 1998. “Codifying the Past, Erasing the Future: NAFTA and the Zapatista Uprising of 1994.” UC Law Environmental Journal 4 (2): 143–62.

Healy, Teresa. 2008. Gendered Struggles Against Globalisation in Mexico. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Harvey, David. 2004. “The New Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession.” Socialist Register 40: 63–87.

Lepawsky, Josh. 2023. “Thinking with Waste to Know the Economic.” Journal of Cultural Economy 16 (4): 587–93.

Locke, John. [1689] 1964. Two Treatises of Government. Edited by Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lowe, Lisa. 2015. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1990. “The Secret of Primitive Accumulation.” In Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, edited by Friedrich Engels. Translated by Ben Fowkes and David Fernbach. London: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review.

Mintz, Sidney. 1985. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Viking.

Muehlmann, Shaylih. 2024. Call the Mothers: Searching for Mexico’s Disappeared in the War on Drugs. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ortiz, Fernando. 1995. Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Paley, Dawn. 2014. Drug War Capitalism. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Peña, Devon G. 1997. The Terror of the Machine: Technology, Work, Gender, and Ecology on the U.S.–Mexico Border. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Rajak, Dinah. 2011. In Good Company: An Anatomy of Corporate Social Responsibility. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ricardo, David. [1817] 1971. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Edited by R. M. Hartwell. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Sinclair, Scott. 2015. “NAFTA Chapter 11 Investor–State Disputes to January 1, 2015.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

———. 2021. “The Rise and Demise of NAFTA Chapter 11.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Smith, Adam. [1776] 1991. The Wealth of Nations. Edited by D. D. Raphael. New York: Knopf.

Walley, Christine J. 2013. Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wolf, Eric R. 1990. “Facing Power: Old Insights, New Questions.” American Anthropologist 92 (3): 586–96.

Woodman, Stephen. 2018. “NAFTA Isn’t a Cure-All for Mexico’s Auto Sector.” Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Wright, Melissa. 2006. Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism. New York: Routledge.

Zlolniski, Christian. 2019. Made in Baja: The Lives of Farmworkers and Growers Behind Mexico’s Transnational Agricultural Boom. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zukin, Sharon. 1993. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Alejandra González Jiménez is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto Centre for Industrial Relations and the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. Her research explores labor and social reproduction in relation to car production in Mexico.

Cite as: González Jiménez, Alejandra. 2025. “Introduction: Anthropology of Free Trade”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/introduction-anthropology-of-free-trade-by-alejandra-gonzalez-jimenez/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).