Paving the way for NAFTA was as consequential for Mexico as NAFTA itself. Mexico’s entry into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came with countless conditions. Amongst them, small enough to be forgotten, was the Mexican government’s creation of SOFOLES (Sociedades Financieras de Objeto Limitado, or Limited Purpose Financial Corporations) in 1993. These limited-purpose financial corporations, seemingly harmless, provided vehicles through which lending could be expanded. Although constrained to a single economic sector and lacking the flexibility and scope of other nonbank financial institutions, SOFOLES were able to operate beyond the strictures of banking regulation.

The function of SOFOLES was, at first, straightforward. They channeled short-term bridge loans to developers with the goal of increasing competition and liquidity in the Mexican real estate industry, thereby spurring activity overall. As limited-purpose financial corporations, SOFOLES could not take nor hold deposits (for that would make them banks), but they could accept various other forms of capital and quickly turn them into loans.

SOFOLES thus absorbed government subsidies and loans, private investment and credit, and short-term lending profits. They then lent these funds to Mexico’s construction companies, increasing those companies’ capacity to operate while charging interest. Though modest in scope compared to multifunctional shadow banks, SOFOLES met an urgent need in Mexico’s highly concentrated and tightly regulated banking industry. Moreover, U.S. finance sought entry into the Mexican market, and SOFOLES provided a convenient vehicle.

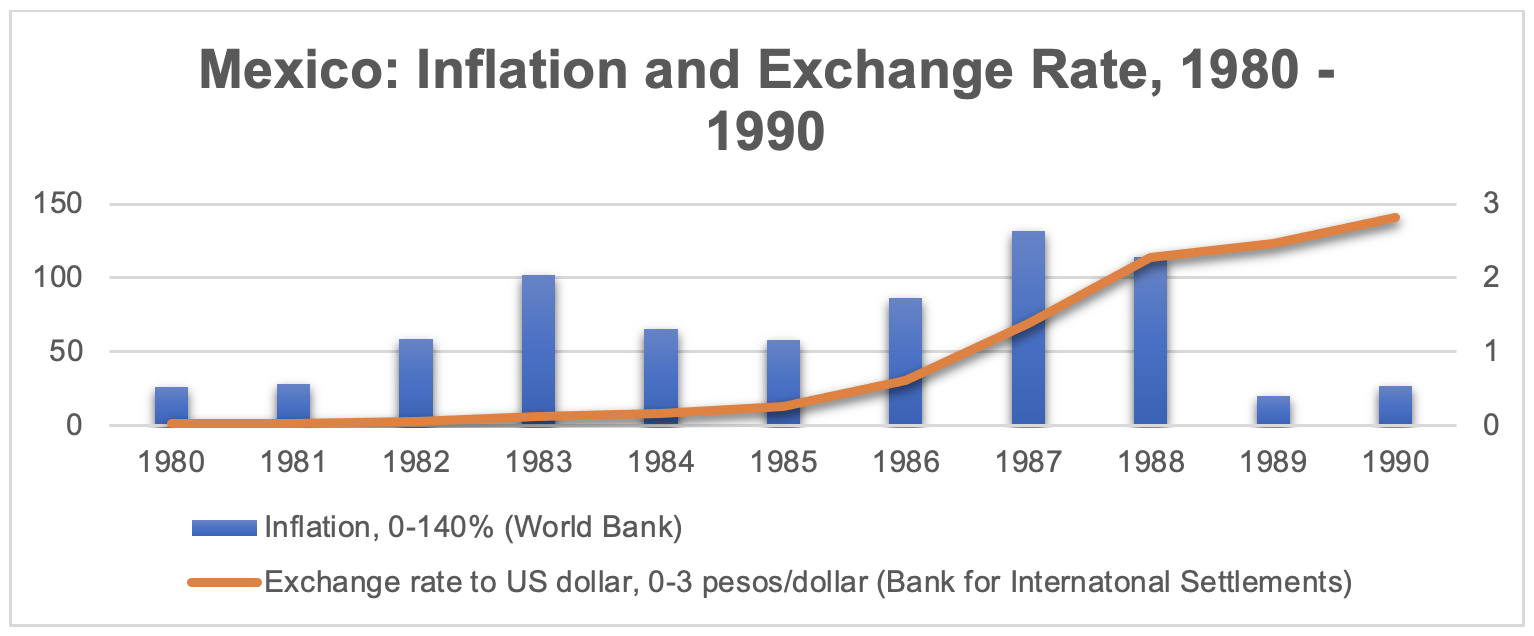

As in many other aspects of economic integration, Mexico could only join NAFTA by remaking itself in the image of the United States, with the country’s macroeconomic viability hinging on this costly project. Mexico’s expensive makeover into a nation fit for North America, moreover, had to be carried out while also keeping the peso stable, the inflation rate flat, and the national debt under control—three formidable tasks under any circumstances, let alone in the aftermath of debt and currency crises of the 1980s.

Figure 1. Mexican rate of inflation 1980–1990, World Bank; MXN-USD Exchange Rate, Bank for International Settlements (graph made by author).

And, yet, in the end, Mexico managed the task. Within a handful of years, for instance, the administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–1994) built Mexico’s contemporary highway and rail network. This expansive and rapidly constructed ground transportation system was a fundamental prerequisite for Mexico to become both a node and bypass of global trade. Monuments erected to memorialize the historic feat still loom today, in decayed splendor, over those who cross the country. Mexico’s vast developmental leap toward North America was also commemorated in song, with the government commissioning a recording featuring virtually every major Mexican artist of the 1980s and 1990s.

Figure 2. Photo of Solidaridad monument, 1 (photo credit: SEFT-1 Project).

Building a road to NAFTA, however, was bankrupting the country. Mexico’s fiscal deficit deepened, threatening a currency devaluation—and, with it, NAFTA’s promise of macroeconomic viability. To avert disaster, Mexico attempted to spend its way out of a looming peso collapse, injecting money into the currency by buying it in great quantities and boosting its value. The government exchanged dollars for pesos to buy time, but more funding was still needed, for only more money could transform Mexico into North America.

To generate the funds required to sustain its North American project while guarding against currency devaluation, the Salinas administration devised a novel solution. Mexico began issuing and selling tesobonos, short-term treasury bills that were purchased in pesos but repaid in dollars. By selling these securities, the Mexican government gained liquidity to finance its transformation while artificially propping up the value of the peso. Yet, as investors eventually cashed out their tesobonos in dollars, the government’s dollar reserves dwindled, increasing its vulnerability and deepening the fiscal strain.

Figure 3. Photo of Solidaridad monument, 2 (photo credit: author, screenshot of Google Maps Street View, Manzanillo-Cihuatlán highway).

On January 1 1994, NAFTA came into effect and, with it, a new Mexico. The country had been gutted and rebuilt to carry the name of North America. Yet the weight proved too heavy to bear, and cracks soon formed in the stability of the peso. In the week following December 20 1994, the Mexican currency lost more than 60 percent of its value. As Mexican industrialists—many burdened with dollar-indexed debts—rushed to offload pesos, global investors joined the exodus. In running against the peso, they also ran against NAFTA, bankrupting the country in the process. Mexico’s reserves were stripped of their scarce dollars as people dumped their pesos, leaving the nation unable to service its mounting national debt.

Amidst the 1994 Mexican peso crisis—or the “Tequila Effect,” as Americans labelled its global aftershock—NAFTA hung by a thread and Mexico’s banking system teetered on collapse. Some banks failed outright as borrowers defaulted on dollar-indexed loans, including the sizeable mortgages for modern mansions that Mexican elites had taken on amid the heady optimism of a North American future. The United States, however, had too great a stake in its southern neighbor to look the other way now. It quickly orchestrated a $50 billion line of credit that cut the peso’s devaluation, stabilized markets, and bailed out Mexican banks. After all, North America itself was in the balance.

Figure 4. Photo of Solidaridad monument, 3 (photo credit: Diego Escobar González [author’s brother], Morelia-Mexico City highway).

This is how NAFTA made Mexico’s subprime mortgage industry. It did so by forcing Mexico to spend money it did not have in order to qualify for North American integration. It did so by demanding that this happen while keeping the peso stable and inflation flat. It did so by requiring these measures in the wake of the 1980s crises. It did so by conditioning the 1994 peso collapse, which justified the banks’ retreat after near-bankruptcy. And it did so by creating SOFOLES, which stepped in to fulfill the role of banks—free from any banking regulation.

Years later, U.S. President George W. Bush (2001-2009) and Mexican President Vicente Fox (2000-2006) signed the Partnership for Prosperity, a binational agreement designed to transform Mexico’s low-income masses into mortgage-backed homeowners. Firm believers in a unified North America, Bush and Fox made SOFOLES their allies in this historic public-private initiative. Under presidential auspices, these limited-purpose financial corporations began lending to Mexico’s poorest borrowers, transforming them into homeowners—and as such, into true North Americans—while bunding and slicing their loans to sell on the mortgage-backed-security market.

The consequences of turning short-term profiteers into long-term lenders for Mexico’s working poor would run deep. For one, the transformation threw existing strategies of social reproduction into crisis by eviscerating patrimony and rendering property a vehicle for endless rent extraction. Or, in the words of Alicia, who became a homeowner through Bush and Fox’s Partnership for Prosperity: “The truth is that this [property] is like another rent. This [house] is not ours, not really, and we always have to keep paying. This house, well, it’s just a drug. But the day I stop paying, that day, I’ll feel like it will be another loss. Just another loss.”

Figure 5. Photo of Solidaridad Monument, 4 (photo credit: Mariana Flores Guevara [author’s friend], Acapulco-Mexico City highway).

Inés Escobar González is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Williams College and a Fellow of the Harvard Society of Fellows. Her research examines the causes, consequences, and historical trajectories of financialization in our social organization and politics, particularly in Mexico. Inés’ first book, After Inclusion: Poverty, Property, and Politics on Mexico’s Financial Frontier (under contract with University of California Press), traces the transformation of low-income households and communities in Mexico as they have been incorporated into flows of global finance by way of development reform, or how and why financial neoliberalism remade poverty on the global periphery. This work also reconstructs the rise and fall of North America as an animating utopia.

Cite as: Escobar González, Inés. 2025. “NAFTA and the Making of the Mexican Subprime Lending Industry”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/in-pursuit-of-north-america-by-ines-escobar-gonzalez/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).