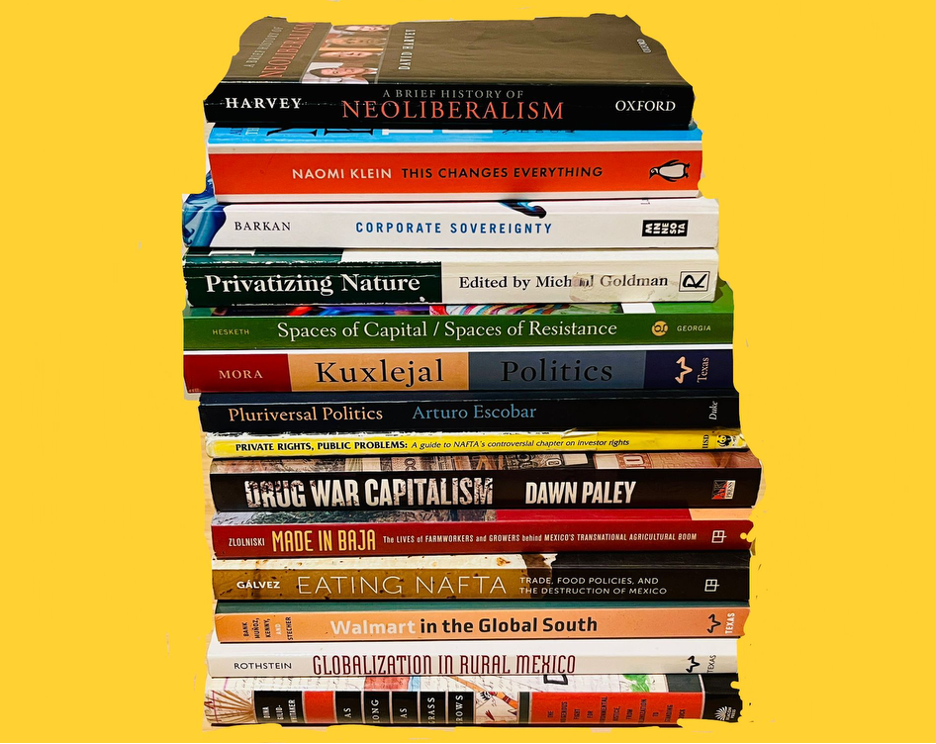

Figure 1. Some of the books I used in my NAFTA: Anthropology of Free Trade course and/or that helped me prepare its conceptual framework. Photograph by Alejandra González Jiménez.

“Do you know what NAFTA is?” I would routinely ask students over the past few years whenever I introduced my research on car production in Mexico. I was often surprised to receive either a “no” or a blank stare in response. This experience led me to design a course on free trade, which I taught twice: first at the Centre for Global Studies at Huron University College in winter 2022, and then at the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies at the University of Toronto in winter 2023. In this essay, I reflect on the challenges of teaching about NAFTA.

I designed the 300-level course titled NAFTA: Anthropology of Free Trade with three goals in mind. First, I aimed to develop an anthropological subfield that I call the “Anthropology of Free Trade.” Second, I sought to teach students about how the contemporary global economy is organized and about the histories that underlie our globalized world. Because most of the world today operates under free trade agreements, it is imperative to understand free trade from the perspective of the humanities and social sciences. Third, I wanted “to make strange the familiar,” introducing students—whether from disciplines such as economics, English, international relations, industrial relations and human resources, political science, or mathematics, or from first-year college programs—to anthropology, qualitative research, and ethnography as ways of knowing the world.

Teaching about NAFTA has proven rewarding, challenging, and at times disheartening. I came to realize that for the generation of students I was teaching—most of them members of Generation Z—free trade was effectively non-existent, despite the pervasiveness of the lifestyles created and enabled by it. By this I do not mean that students lacked an understanding of NAFTA as a set of free-market policies governing and reordering Mexico, Canada, and the United States while reproducing neoliberal ideology. I mean “non-existent” literally: most of my students did not know that a free trade agreement binding Mexico, Canada, and the United States even exists, much less that it predates their own births.

This blind spot, I believe, is symptomatic of the larger historical conjuncture in which we live—a moment marked by a fundamental contradiction between the belief that capitalism, in whatever formation, will ultimately make a “better” world and the reality that capitalism has engendered and continues to thrive on destruction, exploitation, dispossessions, inequality, antagonism, and death. For me, free trade encapsulates this contradiction, which makes a course on NAFTA both urgent and effective.

On Not Knowing

In both my courses, taught across the two campuses, a handful of students knew basic information about NAFTA. Typical responses included: “It is an agreement that enables the trade of goods between the three countries,” “It has eliminated barriers/tariffs/taxes for trade,” or “it aided in the distribution and selling of goods in international markets.” Some of these students, however, did not know that NAFTA had been replaced by NAFTA 2.0. Most students acknowledged that they knew anything about NAFTA or said they “didn’t know enough to have an opinion on whether NAFTA was a good thing or not.”

Canadian and U.S. students in my other courses likewise did not know that their countries are part of a trade bloc with Mexico. International students—most of them from Asia—also seemed unfamiliar with NAFTA. For this demographic, such a gap in knowledge might be expected: why would a student from Asia know about a free trade agreement interconnecting three countries thousands of kilometers away, in different times zones, and on another continent? Still, the widespread lack of awareness puzzled me. For thirty years, free trade has shaped Mexico as a space fertile for direct foreign investment not only from the U.S. and Canada but also from China, South Korea, Japan, India, and, more recently, Qatar.

There could be several reasons for not knowing about NAFTA. I do not claim to know these reasons, but want to venture some preliminary thoughts based on my observations of class dynamics, students’ responses to assigned readings and class questions, and a short anonymous questionnaire that students filled out on the last day of class.

One reason for the students’ not-knowing may be the absence of free trade in the media. After the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, and up to 2016, when Donald Trump promised to renegotiate “the worst trade deal ever made,” NAFTA rarely appeared in mainstream media in either Canada or the U.S. Trump disrupted “business as usual” and in 2018 NAFTA was renegotiated and renamed. Since then, fragments of NAFTA 2.0. have surfaced in English news—often in stories about drug cartels diversifying their enterprises by appropriating the avocado and lime trade, or about how avocado production is driving deforestation and large-scale water extraction.

By 2024 and early 2025, Trump’s nullification of a key component of free trade had brought NAFTA 2.0 into the spotlight. In Toronto’s media, we heard about retaliatory measures, campaigns urging consumers to “buy Canadian” and opt for staycations, proposals for increased intra-provincial trade, layoffs and temporary closures, and discussions about replacing NAFTA 2.0. In Ontario, the “tariff war” became a central theme in the 2025 provincial elections and a vehicle for articulating hierarchies and disdains. The Premiers of both Ontario and Alberta suggested that “Mexico [should] be kicked out of the tri-lateral agreement” because of unfair trade practices, imbalances, the loss of jobs to Mexico, and Mexico’s role as a “backdoor” for cheap Chinese products and investments. For both Premiers, free trade without Mexico would continue “the friendship between Canadian and American people.” Even on my neighborhood listserv, NAFTA and NAFTA 2.0. became topics of conversation. As one student who had taken my free trade course in spring 2024 told me in January 2025: “Before I didn’t hear anything about NAFTA; now I hear about it everywhere.”

Students’ not-knowing may also reflect how NAFTA is intrinsic to the lifestyles created by globalization. Free trade has become a habitus in Bourdieu’s sense. Students growing up in Canada and the United States are part of a generation— unlike their grandparents and, to a lesser extent, their parents— for whom access to certain commodities is taken for granted, especially in so-called multicultural cities such as Toronto or New York City. Off-season fruit and vegetables from elsewhere—avocados, raspberries, limes, papayas—can be bought at large supermarkets such as Wal-Mart as well as in small local stores across Toronto, even in the middle of winter. In sushi restaurants, avocado rolls have become one of the most popular options for vegetarians and vegans. In the United States, 110,000 metric tons of Hass avocados were consumed during the 2025 Super Bowl. Fresh tomatoes and cucumbers sold in Toronto are locally grown in Leamington, both in fields and in greenhouses, by migrant laborers employed on temporary work permits.

Free-trade lifestyles and consumption patterns in Canada and the United States intersect with the ways Generation Z has come of age in an era when the transformations, reconfigurations, and effects of market capitalism, neoliberal ideology, policies, and modes of governance have taken hold of the world and produced what Gershon (2020) calls “common sense.” While some students agree that reliance on fossil fuels must end, most readily embrace profit-making endeavors and market mechanisms as solutions to the climate catastrophe. Many take for granted the fallacy that prices are determined by the “forces” of supply and demand. For them, college is a path to cultivating human and social capital and enhancing entrepreneurial and marketable capabilities. For some, the well-being of a corporation is even more important than their own, as a first-year student once made me realize when she told the class, “Downsizing makes sense if it is for the good of the company.” In such moments, I saw how the logic of economic value trumps other ways of thinking. One’s own disposability has become a legitimate and even logical course of action for the sake of capital and the corporation.

The invisibility of NAFTA is thus the result of a conjuncture: a lack of accessible information, a taken-for-granted lifestyle, and the routinization of neoliberal logic and rationality, which has reduced all aspects of human and nonhuman life to economic value and metrics (Brown 2017), all while quietly permeating the everyday.

An Anthropology of Free Trade

NAFTA has often been touted as a path that would eventually lift people out of poverty by creating wage work, yet its operation has required the savage exploitation of both labor and nature. This contradiction makes NAFTA an ideal object for studying the contradictions inherent in the global economy of the twenty-first century.

A vast body of scholarship on NAFTA focuses on Mexico, especially compared to the paucity of work on Canada and the United States. For this reason, my course centered on how Mexicans live with, make use of, are affected by, navigate, and contest this macro-instrument that, for three decades, has given contour to their lives. Of utmost importance was showing students how the free trade agreement intersects with existing social, economic, political, and historical processes, and how it produces unexpected effects.

My broader aim in teaching a course on NAFTA was to contribute to an anthropological subfield I call the “Anthropology of Free Trade.” Its conceptual toolkit draws on a wide interdisciplinary scholarship, including capitalism in its permutable formations and as a form of structural power (Bourdieu 1998; Coronil 2001; Harvey 2001; Subcomandante Marcos 1997; Wolf 1990), globalization (Hoogvelt 2001), labor (Rothstein and Blim 1992), and the anthropology of policy (Shore and Wright 1997). To examine the genealogy of free trade, we situated it within the historical processes entangling liberalism, liberal law, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism (Frank 1966; Gallagher and Robinson 1953; Galeano 1997; Gill and Cuttler 2014; Lowe 2015) while also discussing how “the law” is a cultural product of—and intersects with—those same processes (Gill and Cuttler 2014). We further considered how, since the inception of free trade, the corporation has been pivotal to colonial and imperial relations of expansion, subjection, and domination (Barkan 2013; Rajak 2014). This interdisciplinary and genealogical framework enabled us to understand free trade as a historical and ever-evolving force in processes of world-making.

To explore how NAFTA is enacted in everyday life, we examined low-paying precarious jobs, workers’ exposure to chemicals, and the environmental impacts of manufacturing and large-scale agriculture, including the massive water extraction required to grow seasonal crops year-round (Funari and De la Torre 2006; Zlolnisky 2019). Although temporary worker programs in the United States (Zlolnisky 2019) and Canada (Binford 2013) are not formally part of NAFTA (unlike professional and investors work permits), migrating under such schemes remains one of the few options available to able-bodied young men—and increasingly, some women)—seeking to escape precarious employment in Mexico. NAFTA 2.0 has been celebrated as the first free trade agreement to include mechanisms to support workers’ freedom of association and union democratization in Mexico. For this reason, we examined cases in which workers have used the Rapid Response Labor Mechanism (Annex 23-A) (Lui 2023).

Students found especially eye-opening the tensions between national development policies and the ways corporate power operates within the global economy (Bakan et.al. 2020). Specifically, we explored three illustrative cases. First, Mexico’s energy transition under market logics (Howe and Boyer 2016) and the dilemmas this creates in post-AMLO Mexico (Kurt 2021; Owen 2023).[1] Second, the ways corporations used NAFTA’s Chapter 11 (ISDS) provisions to sue governments when public-interest measures threatened their future profits (Sinclair 2011). Third, Mexico’s challenge to GMO corn, and how scientific knowledge produced by corporations shaped the ruling in favor of U.S. corn growers and agribusiness corporations (Arnold and Sharrat 2023; Katic 2022).

The course also examined how NAFTA has aggravated violence linked to the war on drugs. This war has enriched Canadian mining companies while producing fertile conditions for the entanglements between “illegal” and “legal” economies (Paley 2014). Cartel and military violence have routinized femicides of maquiladora workers (Wright 2013) and disappearances across Mexico (Muñoz Martínez 2014; Watt 2013). NAFTA’s violence was also examined through the lenses of border militarization (Dunn 1996) and migrant deaths and disappearances (De León 2015). The relationship between NAFTA and the drug economy was further explored (Dube et.al. 2014; McDonald 2005; Muehlmann 2013).

To conclude the course, we juxtaposed two starkly different ethics of being in the world. One came from Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, who remarked: “AI will probably, most likely, sort of lead to the end of the world. But in the meantime, there’ll be great companies” (cited in Gilson 2024). This ethic captures the logic of free trade: an incessant drive for accelerated accumulation, rapid turnover, and the pursuit of billions of dollars regardless of the consequences of violent extraction.

Against this rapacious techno-market ethos, we examined projects that reimagine the world (Beamer 2023; Escobar 2020). We discussed how Los Zapatistas are currently engaged in a process of reconfiguration to prepare for the next 120 years—or the next seven generations—in anticipation of what they describe as “a new phase of systemic and environmental collapse” (Zibechi 2023). This juxtaposition aimed to highlight the temporal disjuncture in which we now live: on one side, the defense of free trade and capitalism; on the other, the long-term imagination of alternatives. As I reminded students, Los Zapatistas continue—as they have done since their legendary rebellion against NAFTA on January 1, 1994—to teach us new ways to imagine economies, relationalities, and solidarities.

By learning about free trade, students got a crash course in global political economy and in the possibilities of countering it. The course provided tools for developing multidimensional and multiscalar thinking—skills that are crucial for our times. Grappling with NAFTA’s entangled realities revealed how free trade connects people, scales, places, and historical processes, even as it devastates livelihoods, biodiversity, economies, human and non-human forms of life. By tracing how free trade makes life and the planet more fragile, I sought to impress upon the urgent need to critically re-think free trade—and its modes of production and consumption— as a developmental path before the climate catastrophe fully overtakes us.

Notes

[1] AMLO is short for Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s president from 2018-2024.

References

Abbott, Jennifer, et al. 2020. The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel. Elevation Pictures.

Arnold, Rick and Lucy Sharrat. 2023. “Canada and the US bully Mexico to use GMO Corn Due to Biotech Lobby Groups.” The Council of Canadians: People, Planet, Democracy.

Barkan, Joshua. 2013. Corporate Sovereignty: Law and Government under Capitalism. University of Minnesota Press.

Beamer, Kamanamaikalani. 2023. 4S Keynote Speech. Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa. Society for Social Studies of Science.

Bindford, Leigh. 2013. Tomorrow We All Going to the Harvest: Temporary Foreign Worker Programs and Neoliberal Political Economy. University of Texas Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. “Neoliberalism, the Utopia (Becoming Reality) of Unlimited Exploitation.” In: Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyranny of the Market. The New Press.

Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone Books.

Coronil, Fernando. 2001. “Smelling Like a Market.” The American Historical Review 106(1):119-129.

De León, Jason. 2015. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. University of California Press.

Oiendrila Dube et.al. 2016. “From Maize to Haze: Agricultural Shocks and the Growth of the Mexican Drug Sector.” Journal of the Economic European Association 14(5): 1181-1224.

Dunn, Timothy J. 2001. “Border Militarization via Drug and Immigration Enforcement: Human Rights Implications.” Social Justice 28(2(84)):7-30.

Escobar, Arturo. 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham: Duke University Press.

Frank, André Gunder. 1966. “The Development of Underdevelopment.” Monthly Review 18(4): 17-31.

Funari, Vicki and Sergio de la Torre. 2006. Maquilapolis: City of Factories. California Newsreel.

Gálvez, Alyshia. 2018. Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies and the Destruction of Mexico. University of California Press.

Galeano, Eduardo. 1997. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. Monthly Review Press.

Gallagher, John and Ronald Robinson. 1953. “The Imperialism of Free Trade.” The Economic History Review 6(1):1-15

Gershon, Ilana. 2011. “Neoliberal Agency.” Current Anthropology 52(4):537-555.

Gill, Stephen and A. Claire Cuttler 2014. New Constitutionalism and World Order.

Cambridge University Press.

Gilson, Dave. 2024. “At What Point Do We Decide AI’s Risks Outweigh its Promise?” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Hoogvelt, Ankie. 2001. Globalization and the Postcolonial World: The New Political Economy of Development. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Harvey, David. 2007. “Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, (NAFTA and Beyond: Alternative Perspectives in the Study of Global Trade and Beyond), 610: 22-44.

Howe, Cymene and Dominic Boyer. 2016. “Aeolian Extractivism and Community Wind in Southern Mexico.” Public Culture 28 (2): 215-235.

Katic, Gordon. 2022. Modifying Maize: How Genetically Modified Corn Changed Science, Academia, and Indigenous Rights in Mexico, part 1 of 2. New Books Network Podcast.

Hackbarth, Kurt. 2021. “AMLO is Nationalizing Lithium Supply.” The Jacobin.

Lui, Meizhu. 2023. “Toothless ‘Protection’ for Mexican Workers.” México Solidarity Bulletin.

McDonald, James. 2005. “The Narco-Economy and Small-Town, Rural Mexico.” Human Organization 64(2):115-125.

Muehlmann, Shaylih. 2013. When I Wear my Alligator Boots: Narco-Culture in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. University of California Press.

Muñoz Martínez, Hepzibah 2014. “Criminal Violence and Social Control.” NACLA: Report on the Americas.

Shalk, Owen. 2023. “Canada is Trying to Stop AMLO From Putting Mexico in Control of its Own Resources.” The Jacobin.

Subcomandante Marcos. 1997. “The Fourth World War Has Begun.” Le Monde Diplomatique.

Paley, Dawn. 2014. Drug War Capitalism. AK Press.

Rajak, Dinah. 2011. In Good Company: An Anatomy of Corporate Social Responsibility. Stanford University Press.

Shore, Cris and Susan Wright. 1997. Anthropology of Policy: Critical Perspectives on Governance and Power. Routledge.

Sinclair, Scott. 2021. “The Rise and Demise of NAFTA Chapter 11.” Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives.

Watt, Peter. 2013. “The Disappeared and Mexico’s New Dirty War.” NACLA: Report on the Americas.

Wolf, Eric R. 1990. “Distinguished Lecture: Facing Power–Old Insights, New Questions.” American Anthropologist 92(3): 586-596.

Wright, Melissa. 2006. Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism. Routledge.

Zibechi, Raúl. 2023. “Zapatistas at 30: Building and Inspiring Autonomy.” NACLA: Report on the Americas.

Zlolniski, Christian. 2019. Made in Baja: The Lives of Farmworkers and Growers Behind Mexico’s Transnational Agricultural Boom. University of California Press.

Alejandra González Jiménez is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto Centre for Industrial Relations and the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies. Her research explores labor and social reproduction in relation to car production in Mexico.

Cite as: González Jiménez, Alejandra. 2025. “Teaching NAFTA”. In “Anthropology of Free Trade”, edited by Alejandra González Jiménez, American Ethnologist website, 11 November. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/teaching-nafta-by-alejandra-gonzalez-jimenez/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Katie Kilroy-Marac (katie.kilroy.marac@utoronto.ca).