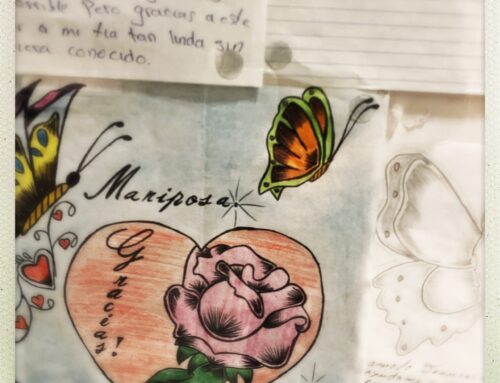

Flowers at the US-Mexico border wall, El Paso. Photo by Ahlam Chemlali

The images have become commonplace: the might of war tanks, the ubiquitous speedboats or all-terrain vehicles; men dressed in camo, patrolling “empty” deserts and “open” seas. Deportation flights and detention centers and points of containment that “appear” in cities more and more distant from the capitals; human remains belonging to migrants discovered in environmentally hostile and remote places. All of these combined constitute the landscape that has become commonplace in Tunisia and Mexico amid the expansion of border externalization, the outsourcing of migration and asylum responsibilities by the Global North to countries in the Global South.

In this contribution, we bring our field observations from two different geographic spaces—Tunisia and the US-Mexico border—into conversation, asking: How are spaces of externalization felt? How are these countries similar and different in enforcing borders and attempting to contain migration?

Once countries of emigration, both Tunisia and Mexico have been transformed into key transit zones. Yet through policies crafted beyond their borders, they have also been made into liminal spaces where mobility is not just interrupted, but in some cases effectively destroyed. These countries now serve as frontlines of EU and US migration control. They are geographies where the weight of global migration governance is disproportionately felt (Chemlali 2024) and where migrants endure the consequences of policies designed elsewhere. What connects these spaces is a growing reliance on externalization.

Tunisia: Displacement masked as humanitarianism

Tunisia, on the Mediterranean’s southern rim, has emerged as a major waypoint for migrants, both Tunisian and Sub-Saharan Africans seeking passage to Europe. This shift accelerated after Tunisia’s 2011 revolution and the prolonged conflict in neighboring Libya. European policymakers, facing rising anti-immigration sentiment and electoral pressures at home, responded not by opening legal pathways, but by building walls farther from home. The EU has poured funding, training, and logistics into Tunisia, fortifying its coast guard with the aim of intercepting migrants at sea and returning them to North African shores (Chemlali 2024; 2025). These actions have been framed as humanitarian efforts to “save lives” and “dismantle smuggling networks” (Sanchez 2020; 2025).

On the ground, these policies tell a very different story. Cynthia, a migrant mother from Nigeria who had fled detention in Libya and became stranded in a humanitarian camp in southern Tunisia, described her desperation to leave the country in an interview with Ahlam Chemlali:

“I can’t stay here anymore. The conditions here are not livable. We are waiting blindly, just waiting and waiting. The kids are growing up with no future. The twins are not finding it easy, but I don’t have a choice. I just [have to] make them understand I don’t have a choice. We are stuck here. Life is not easy here. We can’t be here begging in the streets always… [Looking at the kids] … they should be in school, not in the streets.”

Externalization measures are policies that shift border enforcement responsibilities to countries outside of the destination state, such as funding third countries to strengthen border controls, creating offshore detention centers, or signing agreements that restrict migration before people even reach the border. Evidence has systematically shown that although these measures are promoted as a humanitarian approach to save lives and disrupt smuggling networks, in practice they have limited to no impact on criminal groups. Data further indicate that many migration attempts are self-organized, without the involvement of smuggling actors (Sanchez et al 2021). Instead, efforts to contain irregular migration have produced a climate of systematic precarity for migrants, reinforced by state-sanctioned forms of hostility.

For example, we have witnessed the ways black migrants in Tunisia are pushed further into the margins, rounded up and forced to live in olive fields and makeshift camps, subjected to constant raids and intimidation. As recently as July of 2025, migrant camps in Sfax, in the eastern part of Tunisia, were dismantled by force, with Tunisian security forces including the National Garde burning migrants’ personal belongings and arresting those who resisted. Fatouma, a young Malian mother with two small children, was among those forcibly displaced. From the olive groves outside Sfax, Fatouma told Ahlam Chemlali:

“They came at night, shouting for us to leave. We had nowhere to go, and when we tried to gather our things, they set fire to what little we owned. My children were terrified. I don’t understand why we are treated like criminals when all we want is a safe place to live.”

These actions by the EU funded Tunisian security forces can be described as the logical extension of an externalization strategy. Migrants are deliberately excluded from access to formal housing, work, and health services. Starved of options, many are funneled toward “voluntary return” programs managed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The voluntariness of these returns, however, is highly contested. Civil society actors argue that the conditions migrants face, including hunger, homelessness, and the threat of violence, leave them with no real choice. These programs, critics say, amount to forced displacement masked as humanitarianism.

Mexico: A fresh take on a classic theme

Across the Atlantic, the United States echoes Europe’s playbook. While we recognize the unprecedented nature of some of the practices the second Trump administration has relied on as forms of removal and containment, the practice of outsourcing migration enforcement roles to third countries is far from new. For decades, the US government has concentrated its migration control efforts on the US’s southern border, through a vast system of containment and removal operations facilitated by Mexican authorities, comprised of roadside checkpoints, surveillance technologies, vehicle patrols, raids and detention facilities—what Wendy Vogt conceptualizes as the “arterial border” (Vogt 2017).

While the Trump White House has bragged about the drastic reduction in the number of apprehensions, attributed to the intensified migration control and border enforcement actions of its agents, the decrease is also a reflection of the containment actions conducted by Mexico that clearly predate the return of Trump to power. The threat on the part of the Trump administration to impose stiff tariffs on Mexico did play a role in the decision of Mexico’s president Claudia Scheinbaum to deploy 10,000 members of the Mexican national guard to the US-Mexico border earlier this year to carry out enforcement actions. However, the deployment of militarized entities to Mexico’s border regions to contain migration predated Trump’s most recent demands and can be simply understood as a confirmation of Mexico’s continued commitment to US migration enforcement policy. Members of the National Guard, and the National Institute for Migration—both of which monitor and enforce migration policy in Mexico—systematically engage in acts of abuse, intimidation, corruption and violence, including the kidnapping and forced disappearance of thousands of migrants transiting the country.

For several years, and as in the Tunisian case, Mexican migration authorities have turned to the country’s Southern border to contain and remove migrants. Multiple civil society organizations have denounced how the Mexican city of Tapachula on the border with Guatemala has become a containment area for growing numbers of people who saw their aspirations to enter the US suddenly terminated following the cancellation of the CBP One program. With the possibility of applying for asylum in the US being de-facto terminated, people have few options apart from hiring the services of potential smugglers or guides who advertise their services online, or requesting asylum in Mexico. The latter is a lengthy and cumbersome process, further complicated by the clear reduction of designated resources and availability of asylum services. As a Cameroonian man waiting for his asylum interview described, neither of these are viable options:

“I am here just waiting for an appointment that never seems to arrive. There are times I feel like I am just dying here. I don’t speak Spanish and I want to learn it, but they do not give me the opportunity to do so. I want to work, but they don’t give me the ability to work. I no longer aspire to reach the US, the images of that Alligator place terrify me. I could risk going to Mexico City, but to get there I need a smuggler which I cannot afford. So I don’t know. There is nothing here for me.”

Tunisia, Mexico, and the global architecture of migrant containment

The measures embraced by both Tunisia and Mexico carry serious risks. Both countries lack the infrastructure, legal systems, and resources to host large numbers of asylum seekers. The arrival of migrants and asylum seekers has fueled resentment and violence and has led to innumerable cases of exploitation and abuse alongside desperate efforts for survival. Migrant deaths and disappearances have also increased even as arrivals to both the US and the EU have declined.

Granted, the US and the EU’s actions to offload legal responsibility to other countries have been repeatedly defeated in court (we recall the UK’s now-abandoned “Rwanda Agreement.” Despite their apparent failure, the spectacularity of government actions allow them to appear strong on border and migration control, and ensure the support of their political base. In the US case, these actions include the reopening of Guantanamo to migrant removals, illegally sending migrants to prisons in El Salvador, and flying asylum seekers to Venezuela or even Libya. In the cases of Tunisia and Mexico, the measures generate political leverage that governments can then use to secure financial resources that help strengthen problematic agencies in charge of enforcement and control.

The parallels between Tunisia and Mexico are striking. In both contexts, migration management has been reoriented to serve the interests of the state. The tools—financial incentives, and security cooperation measures run by international organizations—are similar. So too is the rhetoric: broken systems, the need to combat smugglers, the humanitarian imperative. But beneath the surface lies a deeper transatlantic alignment: the desire to keep migrants out at any cost, regardless of the consequences.

References

Chemlali, Ahlam. 2024. “Rings in the Water: Felt Externalisation and Its Rippling Effect in the Extended EU Borderlands.” Geopolitics 29 (3): 873–96. .

Chemlali Ahlam. 2024. “Treading water in transit: Understanding gendered stuckness and movement in Tunisia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50(20): 5210-5227.

Chemlali Ahlam. 2025. Living and Dying in Transit: Violence, Bodies and Survival in the Tunisian Borderlands. PhD dissertation, Aalborg University.

Sanchez, Gabriella. 2020. “Beyond militias and tribes: The facilitation of migration in Libya.” EUI RSCAS, 2020/09, Migration Policy Centre.

Sanchez, Gabriella. 2025. The Facilitation Proposal: assessing the EU’s response to the smuggling of migrants. March 2025:6epa SIEPS, March.

Sanchez, Gabriella, Kheira Arrouche, Matteo Capasso. 2021. Current trends and challenges on the Facilitation of Irregular Migration in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. Euromesco Policy Study 19. EUI, EIMed, UNODC.

Vogt, Wendy. 2017. “The Arterial Border: Negotiating Economies of Risk and Violence in Mexico’s Security Regime.” International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 3 (2/3): 192.

Ahlam Chemlali is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Aalborg University. Her research investigates the politics of life and death in transit, focusing on the human consequences of European border externalization in North Africa and beyond.

A former US law enforcement officer, Gabriella Sanchez is a research fellow at Georgetown University. Her ethnographic work explores the expansion of the counter-smuggling project in both Europe and the US, and the facilitation of irregular migration as a form of care.

Cite as: Chemlali, Ahlam and Gabriella Sanchez. 2025. “Geographies of Containment: Tunisia and Mexico in the Age of Externalization”. In “Bordering and the War on Migration”, edited by Anna Simone Reumert, Wendy Vogt, and Charlie Piot, American Ethnologist website, 23 September 2025. [https://americanethnologist.org/online-content/geographies-of-containment-tunisia-and-mexico-in-the-age-of-externalization-by-ahlam-chemlali-and-gabriella-sanchez/]

This piece was edited by American Ethnological Society Digital Content Editor Kathryn E. Goldfarb (kathryn.goldfarb@colorado.edu).