For nearly a decade, I have been a faculty member at San Jose State, a large university located in the heart of Silicon Valley—just blocks away from tech companies like Adobe, PayPal, eBay, and Zoom. Other regions might dream of Silicon Valley’s wealth and opportunity, but for many of my students, many of who are from working-class backgrounds, circumstances are hardly different than those other, “less fortunate” regions. In normal times, and even in the present moment of crisis, the promise of high-tech pedagogy falls short of its utopian claim to transcend barriers and democratize access.

Ordinary insecurities in the shadow of Silicon Valley produce a temporality of the present that my students experience as a now-time of gnawing anxiety and a future of no future, including depression, hopelessness, and exhaustion. In normal times, many are treading water and exhibit a seriousness, cautiousness, and world-weariness foreign to American fantasies about freewheeling student life. “Partying”—that hallmark of young adulthood that, despite excesses and some moralistic hand-wringing, is really just a necessary period of experimentation and self-discovery–is a conspicuously absent topic and sensibility on my campus. Young adults are, on the contrary, shoehorned into workplace discipline under the banner of “professionalization.” Besides, they’re too busy working (in jobs, not careers) to party.

Even though we are still in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, its effects are ripping through Silicon Valley. Many of our students hold either part-time or full-time jobs, mostly in the feminized and insecure service sector, and are facing mass unemployment. Department chairs on my campus estimate that somewhere between 15-30% of our students aren’t able to make the switch to “remote-learning” because of lost jobs, childcare responsibilities, inadequate access to slick gadgets, or lack of quiet space to listen to Zoom lectures uninterrupted, given overcrowded living conditions.

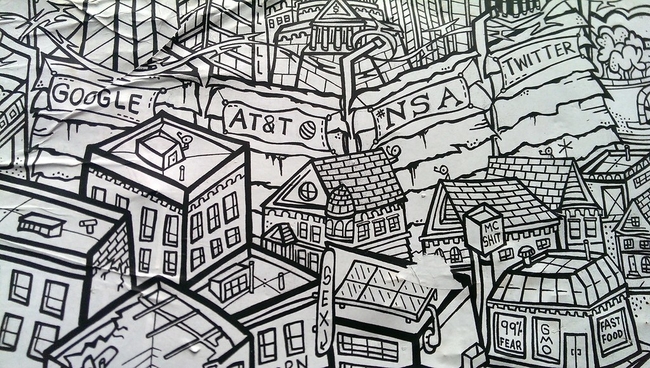

When our campus closed due to Covid-19 social distancing measures, I was contacted by students that told me they didn’t have a stable internet connection and would have to miss my Zoom lectures. Becoming homeless or having previously experienced homelessness is not that uncommon among our students. Not only does the “digital divide” still exist, the instabilities of work, life, unaffordable housing, and a young adulthood plagued by overwhelming social and economic responsibilities make education impossible for many people. This is not something that high-speed internet access, or a slick website, or a new app can fix. And yet that is Silicon Valley’s central mythology and claim to public consent: the myth of the heroic, practical engineer-genius whose technological know-how will secure our utopian future. In times of crisis, media outlets magically transform the engineer-genius into a messiah—Elon Musk promises free ventilators to hospitals; Jeff Bezos’s company delivers everything from toilet paper to face shields with free two-day delivery; and Eric Yuan provides free cloud-based video conferencing to anyone who wants it. Life goes on, virtually.

If tech platforms aren’t really reducing our work, and if they haven’t really demonstrated that much pedagogical efficacy, and their visions of the future are crummy, then what are they really doing? How many faculty have in recent weeks spent hours reading Internet forums about Canvas, or been glued for the entire day to their computers, answering questions over and over again that could have been easily answered in a 30-second classroom conversation? This week I had an online test malfunction—after spending about six hours preparing it and reading endless online forums—and over the course of five minutes an entire page of my email inbox was full of panicked emails. I still don’t really know what went wrong. Is this all the “labor saving” that our tech future promises? It turns out that the old-fashioned technology of a classroom and a social gathering are pretty effective after all these years.

Tech platforms are busy remaking the norms and forms that define the outlines and contours of an educational commodity. They’re remaking what a unit or widget of education looks like—and shaping it into their own image and delivery system, needling their way into whatever new market will have them. Educational tech doesn’t really solve problems that universities are having, such as the socioeconomic problems that students at my institution are facing—it invents problems, creates manufactured wants, and sells a solution (Ewen 2001). It’s marketing is no different than the mythological car salesman. Its goal is to become what Michel Callon (1986) calls an “obligatory passage point” so that when we teach, we are forced to teach to the(ir) technology. Now tech firms and their tools come to control the shape and delivery of education—and at my institution, Silicon Valley ideology and corporate projects come to define the vision and “practical” research topics for the faculty and students. This is a colonization of the imagination.

Photograph by Stephen Shore

My university regularly advertises its relationship to Silicon Valley. Its official slogan, “Powering Silicon Valley,” is a central branding phrase on web pages and other university swag. This may seem trivial. But can you imagine the University of Texas advertising that it was “Powering the Texas Petroleum Economy,” or CUNY “Powering Wall Street”? These everyday reiterations of “Silicon Valley” both name and reinforce a particular kind of imagined community—one that many of our students and their families have been historically excluded from. More than a place (because where is it?) “Silicon Valley” is a narrative, a fantasy, and an imagination of the future. Through a narrative act of future-oriented misdirection, Silicon Valley’s narrative obliterates its past and present by claiming its future inevitability, making an unlivable present seem like a momentary software glitch that will be fixed in the next update. It focuses attention on a major industry while silencing marginalized groups and repressing the recognition of a stunningly uneven economic geography that it is in many ways responsible for. And it soaks our students in this ideology and spectacle, training and reshaping their language and imagination.This pandemic, like other crises, illuminates and forces reflection on gaps in the social fabric and public administration. As many educators turn to learning management systems like Canvas, and online conference technologies like Zoom, there is a chance to misunderstand these tools, to attribute more success to them than they deserve, and to overlook the ways in which they normalize the violation of personal privacy for the sake of convenience. I’m sure that the proponents of Silicon Valley ideology on campus will try to use the current disruption as a justification to radically expand online education, an example of what Naomi Klein (2007) has called “disaster capitalism.”

As many of us are asked to attend seminars about online modalities and read about “best practices” and other business-school babble, I want to push back against the false claims that these online tools are particularly effective or that they actually save time. I think they are actually labor-wasting rather than “labor-saving” devices. Rather than celebrating tech, we should make greater demands on its public accountability and social responsibilities and instead recognize Silicon Valley ideology as an impediment to necessary and bold re-imagining of public and civic visions. Silicon Valley ideology is a hegemony of expertise and an imagination of the future that must be overcome to develop a robust public vision and public response to social crises.

Instead, addressing these problems would require challenging the economics, social priorities, forms of expertise, and especially public investments of a region that touts playfulness and rebelliousness (“think different” [sic]) while stealing the space and time of young adulthood from many of its less affluent residents, and exhibiting an impressive lack of curiosity about those ‘other’ communities that need an engineering “fix.” An industry accustomed to huge tax breaks, dominated by local storytelling that lionizes millionaire heroes and well-educated workers with prestigious credentials, while remaining averse to workers’ unions, and remaining willfully ignorant of its impact on the plight of low-end workers throughout the region. If Silicon Valley is a model of the future, it’s a pretty irresponsible model, especially for a region that revels in self-congratulatory talk of its “visionary” character. It speaks volumes about the narcissism and self-regard of tech leaders. As far as places to live go, for many, “Silicon Valley” is a civic failure—however good it may sound on the Internet. The unfolding coronavirus pandemic is quickly revealing the depth of the problem—and its human consequences.

Silicon Valley’s civic project seems to have only two modes: primitive accumulation and gentrification – or discarding and abandonment. Like corporations, it functions like a privatizing machine that takes from the public, hoards profits, and externalizes losses and waste for the rest of us to deal with. Its misdirections of a hypothetical future lock so many into an unlivable present, what Lauren Berlant (2011) calls a “crisis ordinary,” that cloaks the emptiness of both a lack of public vision or a real imagination of a democratic future. Calling out these failures, illusions, and ideologies for what they are – neoliberal enclosures and the enclosure of civic imagination – and unraveling their hegemony is one step. Telling different stories, installing different forms of expertise, and collecting and re-articulating the voice, experience, and needs of abandoned and discarded communities must replace Silicon Valley ideology. This is not only the ordinary anthropological project of listening at the margins – but also a project of double vision that reconstructs those stories while remaining cognizant that their dissolution, silencing, abandonment, and ruination is the project of Silicon Valley ideology.

Acknowledgements. Thanks to Roberto González for ongoing conversation, insight, and astute editorial advice.

References:

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Callon, Michel. 1986. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fisherman of St. Brieuc Bay.” In Power, Action, and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge, edited by John Law, 196-233. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Ewen, Stuart. 2001. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture. New York: Basic Books.

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt.

Cite as: Marlovits, John. 2020. “Pandemic and Pedagogy in Silicon Valley.” In “Pandemic Diaries,” edited by Gabriela Manley, Bryan M. Dougan, and Carole McGranahan, American Ethnologist website, 2 APRIL 2020, [https://americanethnologist.org/features/collections/pandemic-diaries/pandemic-and-pedagogy-in-silicon-valley]

John Marlovits is a Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at San Jose State University. He has written about depression in Seattle, and is currently working on a project about homelessness in Silicon Valley, as well as another about skateboarding internationalism.